Heidi Kumao‘s art pieces explore ordinary social interactions in order to reveal what lies beneath them: psychological states, emotions, compulsions, thinking patterns, and dreams. She is currently teaching animation, video, experimental television production, and electronic and conceptual art at the School of Art and Design at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. For 2007-08, she has been awarded a Postdoctoral Research Fellowship from the American Association of University Women Educational Foundation.

A few years ago i discovered her set of female kinetic sculptures “Misbehaving: Media Machines Act Out,” and classified her work under robotics and kinetics. Then i stumbled upon the performative techno-enhanced series of clothing she had developed and here i was trying to fit her work inside the “wearable” category. A closer look on her portfolio revealed household objects sabotaged to become cinema machines, overtly activist projects and the geekiest wedding cake i had ever seen. The experience taught me that any attempt to classify of her work would be pure folly unless i’d try to trick her into giving me a helping hand:

Resist, 2002

Resist, 2002

You first graduated in photography at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. How did you come to work with kinetic installations, RFID activist projects and quirky wedding cakes? What made you broaden the scope of your artistic practice?

This is a big question, so I’ll answer it in sections as a way to answer the larger issue of shifts in artistic practice. How I get from here to there to there to there…

Re: transition from photography to sculpture

The Art Institute had a very interdisciplinary photo department at the time and we were really encouraged to “go outside the box” of photography, to mix photography with other media, to be artists who USE photography rather than pure photographers. In the 80’s and 90’s, photography was exploding in 100 different directions and open to a variety of approaches. Everything was possible. Everything could be photographic in some way.

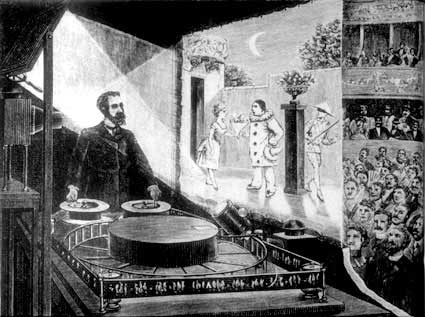

When I entered graduate school as a photographer I was already starting to work with sequential imagery. I was driven by a need to animate physical gestures and behaviors as indicators of psychological states. Simultaneously, I was collecting domestic objects and record players and researching pre-cinema devices and the 19th century creation of spectacle, Emile Reynaud‘s praxinoscope from the 1880’s, in particular. My first kinetic works were homemade-looking zoetropes that projected a sequential loop of 12 images: a child being spoon-fed, a woman’s legs curtseying, a woman frantically sweeping. Like a memory that can’t be repressed, each animated sequence repeated endlessly and mechanically. In this way, each object seemed to be speaking with its images, a visual and mechanical voice replacing text. Much like the girls’ legs I made much later, they were an artificial life form, a stand-in for a real person that I could construct and bring life to. These “cinema machines” (as I called them) allowed me to combine all of my interests (photography, performance, sculptural assemblage and the psychology of everyday life), into one art form. I loved working this way and continued to create cinema machines for several years.

Defense Mechanism

Defense Mechanism

RE: Installation

While much of my work could be categorized as “kinetic installation,” a more accurate descriptor might be “animated tableau.” I tend to think of myself as a theater director, staging events for the viewer. A lot of my art practice is about creating a situation for something to unfold over time. This grew organically out of my experience staging photographs. It seems to be a mode of art making to which I am intuitively drawn.

Each tableau intentionally uses recognizable objects that suggest a possible scenario from everyday life. As I craft each piece, I am very conscious of the psychological experience that is created for the viewer. Can the space of each tableau imply both a physical site and a psychological state? How can I make the viewer re-examine seemingly ordinary events such as childhood play, family dynamics, television news or even the wearing of clothes?

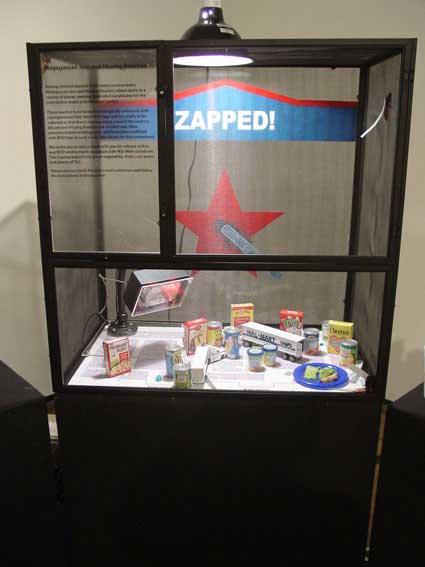

Still from Zapped! video

Still from Zapped! video

RE: RFID Activist projects

I worked on Zapped! a multi-part project about the mass implementation of RFID technology with Preemptive Media in 2005. I met the members of Preemptive Media (Beatriz da Costa , Jamie Schulte, and Brooke Singer at Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh, PA where I was a Microsoft Artist-in-Residence Fellowship for 1999-2000. Besides being a great school for robotics, computing, AI, engineering and art, Pittsburgh happened to be an amazing hub for art collectives, tactical media practitioners, and technological art at that time. I was surrounded by tons of brilliant people including folks from Critical Art Ensemble, Institute for Applied Autonomy, and Subrosa, to name a few. Just being in this environment made me rethink my artistic process completely, and motivated me to learn how to incorporate electronics, microprocessors, computing, and digital imagery into my work.

Before we ever did Zapped! a few of us had collaborated on a project (Nomadika) about data-veillance and wireless technologies for the 2001 Sculpture Conference in Pittsburgh. We educated and informed the public about the future of data mining by opening a storefront for our fake marketing firm. Researching data mining and privacy loss in our contemporary era later led Preemptive Media to the project on RFID, which seemed to be (at the time) yet another way in which corporations and the government would invade citizens’ privacy. As someone who creates and teaches animation and video, my primary role in the collaboration was to make the educational video from all of the research and information we had unearthed as a result of this project.

After working solo for so long, I relished the opportunity to collaborate with others on a project.

RE: quirky wedding cakes

The 6,000 volt wedding cake was a collaborative project with my husband, Michael Flynn, a high school physics teacher and science exhibit designer. As two mechanically minded people, we decided that our cake had to reflect our interests in machines and the project grew from there. It started with the idea to have two cakes cut to look like interlocking gears and progressed to two motorized cakes on gear-run platforms. Michael made two dolls that represented us in our wedding costumes. These dolls were going to stand on the top of each cake and would basically pass one another every time the cakes turned. Eventually, I thought we needed to incorporate an electric “spark” between the dolls, like the “spark” between us (cheesy, I know). This led to the idea of using a Jacob’s Ladder to generate a much larger spark. Michael purchased a neon sign transformer and wired the cakes and dolls with opposing charges. When powered on, the cakes turn, and once a turn, the dolls hands meet and a large flaming spark erupts from their meeting hands. It’s pretty funny. And like other collaborative projects I’ve done, it was loads of fun!. Our “how to” article appeared in Make Magazine.

What made you broaden the scope of your artistic practice?

When I look over the various transitions I have made with respect to media

(from photo to cinema machines to kinetic sculptures to animation to collaborative technological projects), I can map those changes onto personal and cultural moments of change. For many years, I made a life as an artistic nomad. I relocated every year or two for jobs, fellowships or other opportunities. This experience of having to re-contextualize and refocus myself in so many different places shaped my art practice in a deep way. Each time I moved, the new school, city or community raised new issues to consider. For example, (like I said earlier) as a research fellow at Carnegie Mellon, I was exposed to art practices that critically engaged technology rather than simply used technology. I had access to people, tools, and resources such as machine shops for the creation of custom parts, computer programmers, robotics labs, video editing equipment, etc. As a result of being at Carnegie Mellon, my work shifted away from more personal themes towards more political issues and cultural critique.

While I had been using technology for many years, my time at CMU caused me to rethink how I used it and why.

Exposure to such a large computing environment had other long-term effects on my art that didn’t show up until much later. Researchers in AI, computing, robotics and gaming exposed me to the possibilities of generative artwork, which was a complete paradigm shift from creating “fine art” objects for the art world. I was excited to think about making a dynamic system or a tool as an artwork rather than a fixed object. However, it took me awhile to decide on a project that would best be served by this approach.

Later, when I moved to Ann Arbor, Michigan, 9-11 and the proliferation of cable news caused me to analyze the visual and conceptual construction of the news broadcast more critically. CNNplusplus, an interactive and dynamic news broadcast, was born a few years later (in collaboration with Chip Jansen.

Video:

The short answer to your question is simply new places, new people and A.D.D. or the tendency to get bored easily…

You seem to navigate effortlessly from one discipline to another but are there particular issues or elements that you keep returning to?

Yes! I find that I return to an exploration of ordinary social interactions and their psychological undercurrents, institutional critique (mainstream media, traditional gender roles, others), and performance (creating theatrical spectacle, behaving/acting social roles, performing for a camera). I view performance as an integral part of everyday experience and define it very broadly: as a means to define our identity and sexuality, as an examination of roles we play as employees or family members, and as a tool for self-expression. Every piece has its origins in everyday life: an argument, a memory of childhood, the frustrations of watching television, the act of being a consumer–

My art making process is grounded in these types of experiences.

Combining these three things together has produced two main types of work that are pretty different (at least to me):

1) Work that emphasizes a visceral experience and tells a more personal story: the “cinema machines,” the girls’ legs, stop-motion animations, and my latest shadow theater pieces

and

2) interactive projects that are more overtly political and use technology to critique technology: CNNplusplus, Zapped!, Wired Wear

Monitor II: Audio-activated Dress, 2005

Monitor II: Audio-activated Dress, 2005

I find I am drawn to the more personal works because they provide an outlet for me to imply/suggest a critique of institutions of power without being so literal. Almost every piece starts with a personal story of some kind and the creation of a tableau is an opportunity to create a visual poem of images and objects together. By exposing the physical apparatus that drives the bodies into action, I draw a parallel between this machinery and the mechanisms of our unconscious: defense mechanisms, sex drives, thinking patterns, self control, dreams, impulses, instincts.

With the public/interactive projects, the emphasis is more educational and/or ironic. Working collaboratively removes the personal emphasis and creates opportunities to address larger cultural issues and their effects on the general public.

Misbehaving is a series of three female “performers” for intimate installations. What is the performative part of the work?

Misbehaving is a series of three female “performers” for intimate installations. What is the performative part of the work?

Misbehaving consists of three pairs of aluminum, mechanized legs fitted with girl’s shoes: Protest, Resist and Translator. The legs in Protest stomp loudly and unpredictably while standing on a coffee table. In Resist, a pair of girl’s legs squirms on the floor in a way that is both sexualized and challenging in response to viewers’ speech. The girl in Translator is trapped on a track between two “adult” chairs with video projectors for heads. As viewers hand crank her from one side to the other, she becomes like a child caught between two feuding parents, or a political mediator, whose body/screen reveals/exposes the real text of the conversation through non-verbal gestures.

With these pieces, I was thinking about the performance of gender, especially for little girls. We learn what is appropriate behavior so early that it becomes naturalized, we don’t realize that we perform it. In developing these pieces, I wanted to intentionally create girls that perform “badly”, act out, misbehave, or act against type. As machines and girls, these works operate in stark contrast to a culture obsessed with “increasing job performance,” high performance cars, and athletic performance. Their acts of defiance are small, yet powerful, signs of agency.

Videos:

The kinetic girls legs have also some feminist (may i use that word?) undertones. Why is it still important to propose a view on feminism today?

YES, you may (and SHOULD) use the word “feminist.” I consider myself a feminist and I think the stigma around the word (created by conservative males) has (unfortunately) had its prescribed effect of preventing people from self-identifying as feminists.

Those legs were born out of my experience at Carnegie Mellon where I was surrounded by really macho robots: machines that can fight fires or repair a nuclear reactor, robots for combat, robots for Mars, etc. At the same time, television programs were priming the mainstream public for what I call “performative robotics,” including BattleBots and Robo-wars, as vehicles for violent entertainment. With technological art and computing still so male dominated, and the research funding driven by the Defense Department, I do think it’s important to remind ourselves that robotics has a range of applications that are social, psychological, poetic, beautiful, and quirky. Are those feminist, or just alternatives to the mainstream?

I think it’s important to maintain a vigilant feminist critique of the world in the same way that it’s important to be vigilant about racism and economic justice.

Sometimes people forget that feminism has benefited EVERYONE, not just women. Civil Rights legislation in the US has benefited everyone, not just African-Americans. In the developed world, we have this idea that everything has been “accomplished” when really, it’s just a way to keep people complacent and apathetic.

A couple of years ago you developed Zapped! together with the other members of Preemptive Media. The work examines the mass deployment of Radio Frequency Identification (RFID) and its effects on our everyday activities. At the time the website of the project said that “RFID is not yet a household name or a pervasive technology, but Preemptive Media predicts that everyday encounters with this technology (whether known or not) will soon be commonplace.” How much has changed ever since? How much is the public aware of the possible downsides of RFID technology?

In October 2006, the US started issuing passports with RFID chips that include a digital photo and all other information currently printed in passports. These passive tags in passports are only a small beginning of all-around use as they can be embedded into nearly everything you buy, wear, read, or drive. At the time we did the piece, there was a common fear of surveillance–that by carrying items with tags, you could be tracked, your personal data could be compromised, etc. The reality is that the tags need to be scanned at such a close proximity (a few millimeters) that it’s difficult for someone to scan your item without your knowledge. Plus, if all the tag has is a reference number (for another database) rather than concrete data, there isn’t much to gain by secretly scanning…In general, as with so many of these new technologies (GPS, for example), people choose convenience over privacy. In our current climate, you can’t have both. We all love the convenience of having a cell phone, even though they all have GPS chips. You don’t hear people complaining about the possibility of being located through triangulation of their cell phone chip. At least not yet. I think that data privacy is the new “civil rights” issue of our time–at least in the US where there aren’t many data privacy laws.

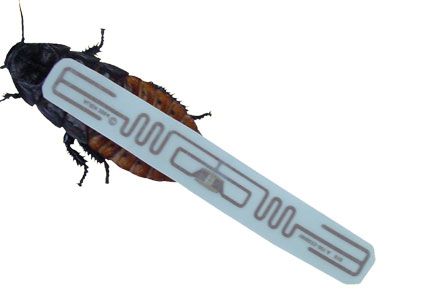

I’ve always been fascinated by the story of the roach release. I saw a brief mention of it a newspaper one day. Can you explain us what it was about and in which context it took place? But also, how did the public react to the idea?

I’ve always been fascinated by the story of the roach release. I saw a brief mention of it a newspaper one day. Can you explain us what it was about and in which context it took place? But also, how did the public react to the idea?

The roach release was but one part of the Zapped! project. The multi-part project included the educational video, a school kit for “arming” yourself against RFID surveillance, the roach release station, and educational workshops. Each of these reached a different segment of the population with the goal of not only informing the public about the technology, but also providing them with means with which they might take action against it.

At the time, WalMart was setting the standards for RFID implementation by requiring its top manufacturers to embed tags into the cases and pallets of merchandise. As the largest retailer in the world, its protocol affects the business practice of nearly everyone in merchandising. WalMart pushed for this change touting its increased inventory efficiency. At this point, we speculated that if a WalMart had RFID readers and a corresponding database, they would all be located in the loading dock/storage area of the store. We discussed different ways to use or subvert the signal of the WalMart RFID reader- for passive tags, it sends a small signal in order to read the information on the tag and puts that information into a database. As we went round and round with ideas for tricking/toying with this Goliath, the idea boiled down to creating a small interruption in/jamming the WalMart RFID database. If WE couldn’t gain access to the loading dock and the readers, perhaps we could send a robot, or, as Beatriz da Costa suggested, a rodent or insect in our place. The final solution was to send a cockroach (with an preprogrammed RFID tag glued to its back) into the store’s loading dock area. The RFID tag was programmed with a small text message of resistance–and would definitely cause a “hiccup” in a database that was accustomed to standardized product information. In the video, we gave instructions on how to do a “roach release,” and in Houston (at Diverseworks), we gave away all the Zapped! roaches. I am not at liberties to say anything about the actual release. The public loved the idea and the roach became the project’s mascot.

Video:

Any other Wal-Mart action?

Not with that piece.

What was the impetus for the audio-activated DRESS? How do you exhibit it (or any of your other wearable pieces for that matter)? As part of a performance? As a static piece in a gallery? As a garment you can lend to gallery-goers?

The wearables started as an idea for a fun Halloween costume. I was initially inspired by the humor that could result from providing visual feedback, especially on a woman’s body. The lights on the dress light up incrementally, starting at the bottom when the sound is softer, and lighting up the entire column when it becomes very loud. When I wear the dress, I become a walking audio-meter which is really an absurd (and poetic?) image. These pieces are custom made to fit my body, and I use them in humorous video performances. The project is less about the objects and more about what I can do with them. So far, I have exhibited them as objects on mannequins with a video that shows them in use. In the end, the final product is really the short videos. There are many more places I can take them…

Videos 1, 2 and 3.

You seem to be attracted by the idea of “intimacy”. Which one of your works expresses the idea better and why?

As an artist, I use machines, projected imagery, and animation because they offer me a visually compelling way to investigate what is unseen: psychological states, emotions, compulsions, neuroses, desires, dreams. I find that I naturally gravitate towards work that examines everyday behavior and personal issues. I’ve called my work “intimate installation” because of its scale (human sized objects), its content (domestic and interpersonal issues) and its viewer experience (dark or dimly-lit rooms). With a minimum of objects, each tableau recreates a private ritual or occurrence for the viewer. I use the word “intimate” to describe the spaces I create and to draw a distinction between my domestic theaters and other large-scale environments.

“Letter Never Sent” is a good example of this. In this piece, video footage captured under a dissection microscope is projected onto the space of the typewriter page. Sounds of a woman weeping, a doorbell ringing, and someone knocking on the door are juxtaposed with black ink creeping up the page and fading, and turbulent, dirty water which seems to spit out from the base of the typewriter. With this piece, I was trying to describe one woman’s difficult experience of writing a letter that is erased or never sent because it is too harsh, too truthful. Rather than use words, I used fluids, like emotions, to wash over the page like a wave. The page is filled and emptied again and again, similar to how one might write and edit oneself in pursuit of the perfect correspondence. Even though the work explores one person’s intimate experience, I think we can all relate to written communication, self-censorship and the strong emotions that result.

Yet another video:

You are also teaching at the University of Michigan School of Art and Design. What are your courses about? Can you give us a few examples of your students’ projects?

At this University, I am mostly teaching animation, video and various conceptual classes (this fall, an introductory class on TIME!). The most enjoyable courses focus on creating material for “experimental television broadcasts,” and rethinking the space of the television as an art gallery for time-based work. I know it seems like an old idea since video art first emerged as an alternative to mainstream television, but here at the University of Michigan, we have a unique collaboration with our local PBS station, WFUM. PLAY is a “collaborative project from the University of Michigan School of Art & Design and Michigan Public Media, transforming the gallery space for time-based media.” This project features time-based work (video, animation, documentary, performance, other experimental forms) by faculty and students in the School of Art and Design. Selected pieces air on television as interstitials-in between programs at the top of the hour, say between “The NewsHour with Jim Lehrer” and “Antique Roadshow,” while all submissions are viewable on the web. In my class, “Animation for Broadcast,” students get real-world experience producing fun promotional pieces as well as content (under 3 min.) for this gallery space we call a television. You can see some of their promo animations here. They were encouraged to think about the concept behind PLAY Gallery (an online, virtual place for art, television as gallery space) and play (the activity). They were given the PLAY logo and could do just about anything with it.

I think it’s a really great moment in history to reconsider what television and broadcast can be, do, say: with the YouTube-ization of the world, everyone’s a performer, everyone’s a filmmaker. How does that impact what we make and produce?

Any upcoming project you could tell us about?

I’m working on some totally new and different works. “Timed Release” is a series of performative portraits focusing on people who have developed a creative mental space to survive physical confinement. Paper cutouts and small kinetic sculptures contained in bell jars or other containers are brought to life through video projection to create illusionary shadow theater. It’s an engaging hybrid of image and object…

Thanks Heidi!