Good news if you’re interested in videogames and plan to be in or around Milan on May 3. IULM Humanities Lab, in collaboration with Standford University, is organizing Games @ IULM, a conference about videogames and their role in education, art, politics. Website’s in italian but i’ll write a report of it after the event.

Via videoludica.

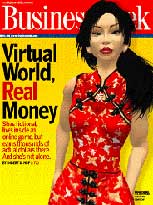

Business Week (via Terranova) has a podcast, two slideshows and a story about Second Life and other MMORLG, money and advertising. Good wrap-up if you’re interested in the topic but don’t have the time to follow it closely (check also The Future of Credit Cards – Earning virtual currency for spending in the real world & other world bridging, by Phillip Torrone.)

Anshe Chung – the “virtual Trump” – even gets the cover of the mag. The land development business, which the avatar has built from nothing two years ago, has turned into an operation of 17 people. Second Life participants pay Linden dollars, the game’s currency, to rent or buy virtual homesteads from Chung so they have a place to build and show off their creations. They can then convert the play money into dollars by using their credit card at online currency exchanges. To handle rampant growth, Chung opened a 10-person studio and office in Wuhan, China. Says Chung’s owner: “This virtual role-playing economy is so strong that it now has to import skill and services from the real-world economy.”

Anshe Chung – the “virtual Trump” – even gets the cover of the mag. The land development business, which the avatar has built from nothing two years ago, has turned into an operation of 17 people. Second Life participants pay Linden dollars, the game’s currency, to rent or buy virtual homesteads from Chung so they have a place to build and show off their creations. They can then convert the play money into dollars by using their credit card at online currency exchanges. To handle rampant growth, Chung opened a 10-person studio and office in Wuhan, China. Says Chung’s owner: “This virtual role-playing economy is so strong that it now has to import skill and services from the real-world economy.”

Unlike in other virtual worlds, SL’s technology lets people build anything they can imagine. In 2003, Linden Lab allowed SL residents to retain full ownership of their creations. The inception of property rights in the virtual world made for a thriving market economy. Tringo, a game played by avatars inside SL, is so popular it was licensed to a publisher, who’ll release it on video game players and cell phones. Some suggest Second Life could even challenge Microsoft Windows operating system as a way to create entertainment and business software and services.

Other real-world businesses are paying attention as virtual worlds could provide them with a new template for getting work done, from training and collaboration to product design and marketing. For example, Rivers Run Red is working with real-world fashion firms and media companies inside Second Life, where they’re creating designs that can be viewed in 3D by colleagues anywhere in the world.

Players are estimated to have spent about $1 billion in real money last year on virtual goods and services at all these games combined. A player in Project Entropia last fall paid $100,000 in real money for a virtual space station, from which he hopes to earn money charging other players rent and taxes.

Some SL 3,100 residents each earn a net profit on an average of real $20,000 in annual revenues. Take Chris Mead who creates animations for couples: When two avatars click on a little ball, they dance or cuddle together. They take up to a month to create but every day he sells more than 300 copies of them at $1 or less apiece.

Second Life’s economy has also begun to attract financial businesses. One character has set up the Metaverse Stock Exchange inside Second Life, hoping it will serve as a place where residents can invest in developers of big projects like virtual golf courses.

Such efforts are raising questions. Virtual worlds may be games at their core, but what happens when they get linked with real money? Ultimately, who regulates their financial activities? And doesn’t this all look like a great way for crooks or terrorists to launder money?

Residents spend a quarter of the time they’re logged in creating things that are available to everyone else. Linden Lab charges customers anywhere from $6 to thousands of dollars a month for the privilege of doing most of the work.

Now companies are thinking about using gaming’s psychology, incentive systems, and social appeal to get real jobs done better and faster. “People are willing to do tedious, complex tasks within games,” notes Nick Yee. “What if we could tap into that brainpower?”

A Palo Alto startup, Seriosity is exploring whether routine real-world responsibilities might be assigned to a custom online game. “We want to use the power of these games to transform information work,” says Seriosity CEO Byron B. Reeves.