Last post about BIP2010, the 7th International Biennial of photography and Visual Arts in Liège. There’s much more i would like to write about but given the appalling high amount of reports and reviews i still have to blog, it is probably wiser to stop the flow here and let your discover the rest of the biennale for yourself if you happen to be in Liège in April.

Previously: BIP 2010 – Equilibrium and Accident and BIP 2010 – Out of Control, Berlin.

The BIP2010 biennale is distributed into several location in the city of Liege, each venue focusing on a different aspect of the general theme: Out of Control.

The Theater of Authority was the exhibition i liked the best. Not only because of the artists i discovered there but also because of the magnificently decrepit state of the building that hosts it. Europe has long been converting ex-warehouses and other industrial spaces into glorious cultural venues but never before had i witnessed such a stylish shabbiness.

A very inviting street entrance

A very inviting street entrance

A gentleman in the courtyard

A gentleman in the courtyard

Trash bags inside the exhibition space. I found them very neat

Trash bags inside the exhibition space. I found them very neat

View of the exhibition space

View of the exhibition space

I might sound ironic but i was truly charmed by the place.

Now how about the show itself? Its premise will sound familiar to most readers: The Theater of Authority explores how our perception is mediated by and eventually adapts to the images coming from inquisitive medias such as satellites and security cameras. Everywhere around us, screens are showering our retina with information most of us hardly ever take the trouble to cross check. We tend to forget that these images are not first-hand, they are mediated, selected and distributed by media, political or scientific authorities.

Katja Stuke, Toronto 2005

Katja Stuke, Toronto 2005

Whether we like it or not, we are not only the resigned receptors of those images, we are actors as well. The anonymous gaze of surveillance devices, now ubiquitous in urban spaces, is following our every step. The photos shown in the exhibition Theater of Authority raise a number of pertinent questions: What happens when we confront this “authority of the visible”? When we push it to its limits? Or when we use and misuse it?

Claudio Hils‘ stunning photo series documents a ghost town located in Senne, North Rhein-Westphalia (DE). Until recently, Senne was a British training ground for military emergencies. Everything about the place is fake, especially the targets in the shape of human beings wearing old fashioned clothes. Meant to enliven the city, the mannequins have the effect of highlighting its emptiness and bleak atmosphere.

What is real though are the traces of military activity. Holes in facades, damaged targets, cartridge cases on the floor, etc. The series is called “Red Land – Blue Land”, a code for maneuvers, Red Land stands indeed for enemy, Blue Land for friendly territory.

Claudio Hils has chosen a documentary, factual approach which leaves the viewers with the task of building up their own scenarios and explanations.

Close Quarters Battle Range, Disco

Close Quarters Battle Range, Disco

Claudio Hils, Close Quarters Battle Range, woman in telephone box, 2000

Claudio Hils, Close Quarters Battle Range, woman in telephone box, 2000

Claudio Hills, Close Quarters Battle Range, Man with Attacking Dog, 1999

Claudio Hills, Close Quarters Battle Range, Man with Attacking Dog, 1999

Close Quarters Battle Range, Post Office Counter

Close Quarters Battle Range, Post Office Counter

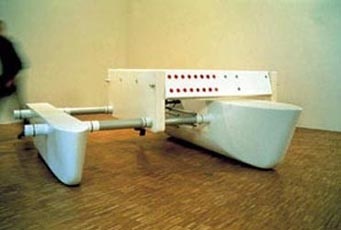

Ange Leccia’s Arrangement Stasi is made of two original East German closed-circuit surveillance camera units which he acquired from the Ministry for State Security.

The lenses of the camera are barely a meter apart, they overlook each other so that the only thing visible within each camera’s field of vision is the lens of its twin. Meanwhile, a pair of monitors screens the pictures registered by each of them.

The installation remind us that one of the problem faced by the STASI bureaucracy was the difficulty to process the absurdly overwhelming amount of data its structure was collecting. Similarly, one can wonder whether there really is any attentive gaze behind the cameras that are monitoring our behaviour in public space.

Ange Leccia, Arrangement Stasi, 1990

Ange Leccia, Arrangement Stasi, 1990

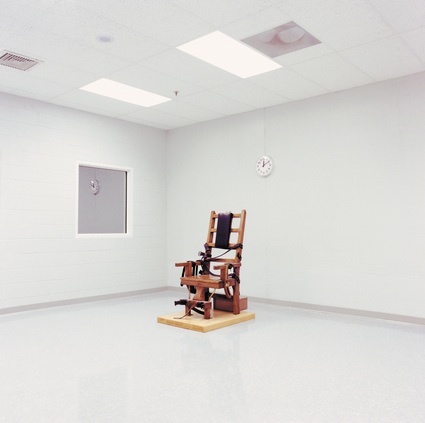

In her work, Lucinda Devlin explores how architectural spaces express the values of the culture that creates and uses them.

Between 1991 and 1998, Devlin traveled through some 20 states to photograph in penitentiaries, with the cooperation of the local authorities. The Omega Suites series -an allusion to the final letter of the Greek alphabet as a metaphor for the finality of execution- portrays execution chambers, holding cells, viewing rooms and other spaces associated with the act of institutionalized killing. With over 3000 inmates on death row and a large majority of US citizens supporting the death penalty, the almost clinical images bring to light one of the most disquieting ethical questions facing contemporary Americans.

Lucinda Devlin, Electric Chair, Greensville Correctional facility, Jarratt, Virginia, from the series The Omega Suites, 1991. Courtesy Galerie m Bochum (Bochum)

Lucinda Devlin, Electric Chair, Greensville Correctional facility, Jarratt, Virginia, from the series The Omega Suites, 1991. Courtesy Galerie m Bochum (Bochum)

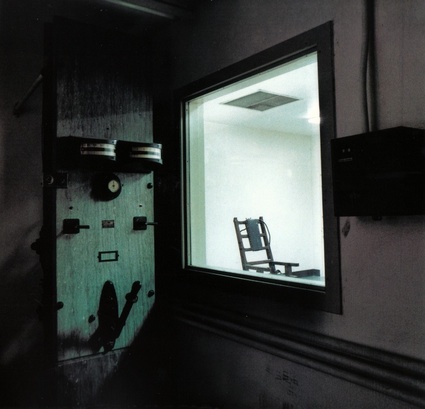

Executioner’s Room, Greenhaven Correctional Facility, Greenhaven, New York, 1991

Executioner’s Room, Greenhaven Correctional Facility, Greenhaven, New York, 1991

Philippe Meste, L’Attaque, 1993

Philippe Meste, L’Attaque, 1993

November 13 1993. Philippe Meste attacks with his ludicrously tiny “War boat” the military harbor in Toulon. The rockets he crafted in his artist studio manage to damage the aircraft carrier Foch and other military ships anchored in the harbour. The artist’s boat is seized by the police and returned only five years later.

Meste’s actions are motivated less by a urge to criticize the army than by a desire to test the limits of what is acceptable and tolerable, in the name of art. At first sight, his attack seems to be pathetic but i also reawakens our fear of insecurity and violence in the middle of an otherwise quiet Mediterranean city. The means and arsenal of war are, after all, ready to be activated should any agitation more threatening than Meste’s emerge.

Philippe Meste, L’Attaque du port de guerre de Toulon, 1993, video Courtesy Aeroplastics contemporary (Bruxelles)

Philippe Meste, L’Attaque du port de guerre de Toulon, 1993, video Courtesy Aeroplastics contemporary (Bruxelles)

Paul Seawright‘s Hidden is a photo response to the war in Afghanistan in 2002. The minefields and battle sites in the images are eerily tranquil and composed. They nevertheless betray the presence of a violence that could be set in motion again.

Paul Seawright, Valley, Afghanistan, 2002 from the series Hidden. Courtesy Kerlin Gallery (Dublin)

Paul Seawright, Valley, Afghanistan, 2002 from the series Hidden. Courtesy Kerlin Gallery (Dublin)

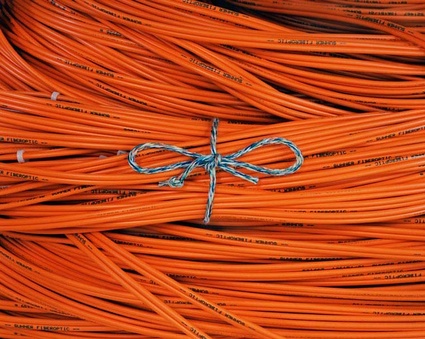

“I’m sorry, Dave, I’m afraid I can’t do that” declares HAL in his dispassionate voice before taking full control of the ship’s operations from the human crew. Simon Norfolk borrows the quote from 2001: A Space Odyssey to name a series of photos portraying some of the supercomputers working in silent locations around the world. The ultra powerful machines administer internet connections, decode human genome, calculate the physical phenomena taking place inside a nuclear warhead when it explodes, etc. Technology at its most fascinating and frightening. Like HAL, the supercomputers were designed to assist humans but they are also unable to sympathize with our logic and dilemmas.

Simon Norfolk, Designing Nuclear Weapons, from the series The Supercomputers:I’m sorry Dave, I’m afraid I can’t do that

Simon Norfolk, Designing Nuclear Weapons, from the series The Supercomputers:I’m sorry Dave, I’m afraid I can’t do that

Simon Norfolk, Cray, XT3, 2.6 GHz, from the series The Supercomputers:I’m sorry Dave, I’m afraid I can’t do that

Simon Norfolk, Cray, XT3, 2.6 GHz, from the series The Supercomputers:I’m sorry Dave, I’m afraid I can’t do that

Simon Norfolk, Cooling system (after Max Ernst) Swiss National Supercomputing Centre, from the series The Supercomputers:I’m sorry Dave, I’m afraid I can’t do that

Simon Norfolk, Cooling system (after Max Ernst) Swiss National Supercomputing Centre, from the series The Supercomputers:I’m sorry Dave, I’m afraid I can’t do that

A BOMB – Beauty of Destruction is a stunning collection of rare and original images compiled by Galerie Daniel Blau in Munich. The photos record nuclear tests performed in the ’50s and ’60s in Nevada and in the Pacific Ocean, explosions in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, some of them are press impressions, other come from the military, the rest were used for research.

The images of atomic explosions are as beautiful as the horror they represent. They are the ultimate theater of authority.

US Army, USS Agerholm in front of Swordfish, Operation Dominic, Christmas Island, May 11, 1962, from the exhibition A BOMB 1945/62 · Beauty of Destruction II. Courtesy Galerie Daniel Blau (Munich)

US Army, USS Agerholm in front of Swordfish, Operation Dominic, Christmas Island, May 11, 1962, from the exhibition A BOMB 1945/62 · Beauty of Destruction II. Courtesy Galerie Daniel Blau (Munich)

BIP2010, the 7th International Biennial of photography and Visual Arts in Liège, is open until April 25, 2010.

BIP2010, the 7th International Biennial of photography and Visual Arts in Liège, is open until April 25, 2010.