Meet one of my favourite Berliners! Christine Hill invited me last year to give a talk at the Bauhaus University in Weimar where she heads the Department Media, Trend and Public Appearance. That’s how i got to know her, i then googled her name and immediately realized the extent of my ignorance when i discovered that she has been exhibiting all over the world with a very unconventional and intriguing project (or should i label it “production label”?) called Volksboutique.

Volksboutique began as a thrift store/sculptural installation in Berlin back in the ’90s when she left New York and landed in Germany. Visitors would open the door to her underground shop, tea was served, clothes were cheap and people congregated to discuss topics ranging from identity and self presentation, to weather and the effect of tourism on the neighborhood (via).

Volksboutique began as a thrift store/sculptural installation in Berlin back in the ’90s when she left New York and landed in Germany. Visitors would open the door to her underground shop, tea was served, clothes were cheap and people congregated to discuss topics ranging from identity and self presentation, to weather and the effect of tourism on the neighborhood (via).

Volksboutique projects kept on evolving, surprising and questioning the audience and the art world. She franchised the boutique for Documenta X in Kassel in 1997, then abandoned her role as a salesgirl and mutated into a late-night talk-show host, a tour guide, a masseuse, a handbags and retro-looking stamp kits designer, etc. Turning everyday job into an artistic activity that could either be presented inside galleries or taken on the road inside carefully crafted trunks.

She is currently showing one of Volksboutique manifestations, Minutes, at the Venice Biennale of Art. This interview was made before the Venice art exhibition.

A book about your work “Inventory : The Work of Christine Hill and Volksboutique” has been published recently. How did it feel? Like a chapter of your professional life that had been turned?

Not to invoke a too-female metaphor here, but that book was as much birthed as it was published. The compilation process was pretty strenuous and I almost fell over when my editor mentioned that “the next book will be much easier” for inability to ever comprehend ANOTHER book. But indeed, there will be another book, as soon as this month! So, I survived the first Volksboutique Inventory. But of course, having an opportunity like that one was incredible, and making the book into a project became my primary task that entire year. I like to keep order, and surveying the projects made since I really began working professionally (depending upon when that actually was) was incredibly satisfying.

Not to invoke a too-female metaphor here, but that book was as much birthed as it was published. The compilation process was pretty strenuous and I almost fell over when my editor mentioned that “the next book will be much easier” for inability to ever comprehend ANOTHER book. But indeed, there will be another book, as soon as this month! So, I survived the first Volksboutique Inventory. But of course, having an opportunity like that one was incredible, and making the book into a project became my primary task that entire year. I like to keep order, and surveying the projects made since I really began working professionally (depending upon when that actually was) was incredibly satisfying.

Initially, I thought of this book as a sort of end of year Annual Report, and was thinking of course about summing up.

I also was glad to have the opportunity to formally define what makes up Volksboutique for me, as it has often been (mis)understood as solely a second-hand shop. The book was the opportunity to show breadth, and to also underscore the aesthetic and “philosophical” stance I take. I also write a fair amount, and the book was the perfect showcase for that activity.

It was an incredibly tidy feeling to draw the line somewhere and say to myself “All this has been accomplished”, but then a sort of enormous void was staring at me, as in “what now?” This is rather familiar to me after large projects.

And as I’ve gotten increasingly interested in libraries and other archiving systems, I am happy to be working on books that can show that interest.

Why these deliberate confusions between art and commerce?

Well, I’m quite interested in properly defining which things are assigned value. And I’m very preoccupied with what counts as labor.

This began quite practically following my move to Berlin in 1991 — with my larger project of assimilating. It is noteworthy that I had no real permission to work here, and so I devised series of service pieces in the early 90s, where I, for example, worked as a masseuse, largely for tips. Also, that I was included in (and working for) numerous group shows all over Europe at this time, and realized that, rewarding as that is, it doesn’t pay money.

This idea of merging income and art occupations culminated with opening the Volksboutique-as-shop in 1996. It was a way of claiming autonomy. It both freed me from being anyone’s employee, and launched me straight into Proprietor-status, and it absolved me from having to rely on the art system to provide me with an audience. It allowed me to build a base of operations, and work from it, which is a device I’ve held onto over years.

“I’ve always held the belief that art is labor that deserves proper compensation. It is often difficult to assert this, in all levels of the art system. I’m sure that all involved would agree that art has “value”, but where the work lies, and who is paying for it becomes a very clouded issue. I have issues with the premise that art is its own reward.”

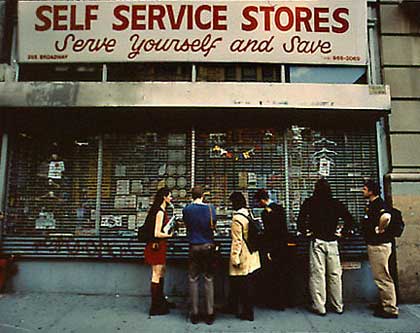

My work path over years has continued to punctuate my thoughts on this, in the form of anecdote or in specific exhibition or project experience. A museum I did a project with revoked a small production fee when they discovered that the piece I had made — a vending machine — was turning a small profit within the exhibition itself. Hundreds of visitors to my installation at documenta X (a franchise of the Volksboutique shop, installed in the exhibition) complained loudly that this “wasn’t a commercial exhibition!”, missing the irony that, for example, a Jeff Wall was hanging directly opposite my store. Numerous visitors (including a reporter from The Wall Street Journal) found my $12 tour fee as part of my Tourguide? piece in New York city excessive, although that is exactly the sum charged by all tour guide agencies in the city. A museum director in Italy refused to refund my travel and production costs for the installation, barking at me that I was “lucky to be in Italy”.

Volksboutique Franchise, 1997

Volksboutique Franchise, 1997

On the one hand, we have art fairs and Sotheby’s auctions reminding us all the time about the financial inequalities or excesses of the art system, but then, on the other, we have puritan calls for the work to be freed of economics so that it can exist in some reality-free bubble. And I disagree with both of these extremes.

Of course, I am isolating these experiences to underscore this particular point. It should not be misinterpreted that my entire work path has been a litany of complaint or abuse. To the contrary. Most artists I know find themselves being pushed forward by “mistakes” or such experiences, and I am no different. Hitting a point of adversity, whether within one’s own process or from the outside, pushes things forward.

Basically, I identify with being a working artist – I work hard in order to live from this and live AS this. And it’s important to me to feature that in projects. And it is important that that include financial aspects.

Of course, when I am involved is larger scale projects — which I call “Organizational Ventures” – that contain large amounts of administration, preparation, and on-site labor, I am often asking myself what I am trying to prove to myself by creating these insanely confounding schemes. It IS the addition of chaos, of overwhelming-ness, of over-stressing productivity that ends up defining many of these projects.

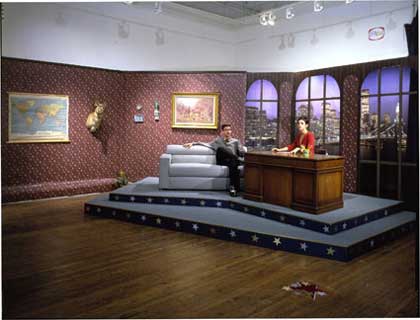

Pilot, 2000

Pilot, 2000

Do you perform or role-play with Volksboutique? How do you differentiate one from the other?

It is good that the the word “performative” has entered the general art vocabulary, because it rescues work like mine from being labeled as Performance Art. I am extremely averse to theater, because I don’t want to see a simulation of life. I want life. I want things real and in real time. And there is always going to be that unfortunate leap the mind makes when hearing the phrase “performance art” that conjures the stage whisper, or someone setting themself on fire. So I don’t consider myself to be performing in the sense that we understand “acting” or staging. But I DO find that the entire thing is about performance, in terms of what in German is the word Leistung. And I do have a certain public persona that is in the work (and probably in my teaching as well). It is a part of my own personality, not something that is assumed, but it is also specific to certain projects that contain an extroverted element. Initially, my labors in the Volksboutique were specifically about pointing directly to the fact that this was an occupation. Something all-consuming, that required a sweat to be broken. And about clarifying that my own person/a was the guide through this set of ideas. This is also a way of addressing accountability and responsibility. Projects of mine require participation of various levels by viewers. How much they can access has in part to do with how they approach me as the representative of any given work. I feel this is a fair exchange, similar to any in a shop transaction.

Tourguide?, 1999

Tourguide?, 1999

Which criteria guide the choice of the identities you adopt in the Volksboutique performances?

I spent one year at a university before switching to an art school, and while I was there, I remember being astonished at the number of extremely focussed majors some people had. I had no idea that these occupations existed. In high school, I was told by those in the position of advising me that I would be a good artist or a good lawyer. (I will assume because I was generally considered a “creative type” but I was also extremely loud and opinionated.) My step-mother thought I should become a dental hygienist. Upon graduating from art school, though my occupation as artist was never really something I questioned, I realized I missed many aspects from other occupations. I remain infinitely curious, for example, about office culture, although I’ve never worked in a true cubicle-zone ever. My initial incarnation as shopkeeper at the Volksboutique was mostly informed by my taking German service culture to task, not to mention wanting to define publicly what I felt was the role of the artist in the society, and that this was a service providing role. Thereafter, I began investigating which jobs would best illustrate my preoccupations. I am particularly interested in librarians now, for example.

I suppose it is redundant to mention these works also point out my femaleness to an extent. Either I have chosen to take on some stereotyped female roles (shopgirl, librarian) or I am intentionally trying out things that fewer women end up in (late night talk show host).

Volksboutique, 1996-1997

Volksboutique, 1996-1997

One of the more reproduced photographs from the Volksboutique store shows me holding up an actual debutante’s ball gown in a wall-sized mirror. There was a fair bit of sniping regarding that image, that it was self-serving or narcissistic, etc. But what it was was my trying something out that interested me. Sizing it up, putting it on.

The aesthetic of the Volksboutique object is very peculiar. What inspired it?

The name Volksboutique stems from the VEB, or VolksEigenen Betrieb, which was the socialist term for collective ownership and industry in the GDR. I moved to Berlin Mitte in 1991, and it was a profoundly different aesthetic experience than today, not to mention from that which I was accustomed having grown up in the States. The remnants of the GDR were everywhere, literally cast out on the street in piles day by day. I wandered the streets daily hauling in everything I could physically transport home. A store called “Dumping Kuhle” sold off stockpiled VEB products that were suddenly rendered valueless. That was the environment I lived in, and so it naturally entered my work.

The name Volksboutique stems from the VEB, or VolksEigenen Betrieb, which was the socialist term for collective ownership and industry in the GDR. I moved to Berlin Mitte in 1991, and it was a profoundly different aesthetic experience than today, not to mention from that which I was accustomed having grown up in the States. The remnants of the GDR were everywhere, literally cast out on the street in piles day by day. I wandered the streets daily hauling in everything I could physically transport home. A store called “Dumping Kuhle” sold off stockpiled VEB products that were suddenly rendered valueless. That was the environment I lived in, and so it naturally entered my work.

However, this is not exclusively a GDR nor Ostalgic thing. My residence in Brooklyn had me obsessed with visual elements I found locally, for example, my studio there is housed in a former pencil factory. Many elements invoke a hand-made aesthetic, and I have a predilection for cast-off objects. I collect 50s office furniture, vernacular signage, manual typewriters, and have a mini-museum of vintage stationery products.

Volksboutique is to a large extent about examining concepts of “value� in our culture and re-investing discarded appurtenances with meaning and use. I’m trying to point viewers’ attention to specific objects and events in life that risk being overlooked as being too quotidian or too common.

One of the mottos of Volksboutique is “Make the most of what you’ve got.” Are there examples in your life when you had no choice but “make the most of what you had”?

I think I could answer this many ways. In my family, there is a particular tic to be constantly striving for a point of “readiness” or “departure” that is pretty unattainable, and can be frustrating. What I mean here is, that “work” can only get done once every little other thing is done — dishes washed, clothes straightened, recycling out, checkbook balanced — rendering a clean slate so that this WORK can begin. But this is a state that will never really be attained! I realized pretty early that rather than waiting for this ultimate constellation or alignment of graces, or whatever, that I simply had to jump in and work with whatever was at hand. This could easily be seen in financial terms, that when XXX stage of financial security is arrived at, THEN XXX can be achieved. Rather than waiting for an impossible or utopian situation to suddenly arise, better to get to work and create a better situation. I mean, I moved to Berlin with no permission to be here, not speaking the language, and with really no obvious skill set that differentiated me from anyone else…and so working within these limitations became my project.

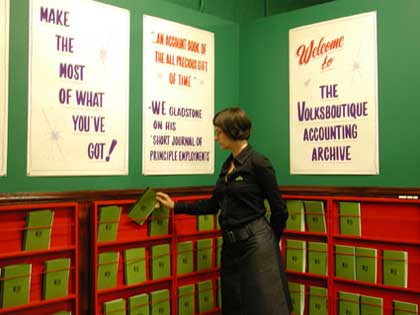

Volksboutique Accounting Archive, 2002

Volksboutique Accounting Archive, 2002

With regard to being a practicing artist, especially since entering the teaching community, there is this misunderstanding to dispel that one entered an art career with other cards than anyone else. What I mean here is that I went through the same channels that anyone would: art school, move to urban environment, work, dialogue within the art system. People are not born with cards optioning them to art careers, (or any careers). There is no mystical thing that suddenly bestows an artist with a career. An artist works and finds him/herself in the midst of it.

I also understand art making to be less about the invention or construction of new things, but more about the close paying attention to and realignment of existing things.

What is Christine Hill doing when she’s not keeping the shop? I’m particularly curious about the work of your students.

Well, I make a lot of lists. And I am a master procrastinator. It is sort of a job in itself. But yes, one of the larger re-structurings of my work life since 2004 is that I teach full time at the Bauhaus University. I chair the department “Media, Trend and Public Appearance” within the media faculty. This is something that sort of serendipitously presented itself to me, and turns out to have been fairly revolutionary for me. I am lucky that teaching is less a diversion from what I normally would be doing, rather it is a pretty natural extension of what I do. And though it has taken some getting used to in terms of the organization of my working time, I find myself impressed and inspired by my students to an amazing degree. The math for embarking on a career as an artist is not necessarily in one’s favor, and the culture — even if we happen to be in some art market boom right now – doesn’t necessarily jump over itself in appreciation for the artistic occupation. So these people are incredibly brave, and I appreciate them following their instincts, and their being uncompromising about what they demand from their lives. And it is there that I can offer the most guidance. I am not necessarily sitting with them teaching them software or how to patina something to a particular finish. More so, it’s training them for the long fight. To instill in them a rigor, so that they can go out with that in their toolkit. I’m not trying to scare them, but I am trying to explain to them what will be required of them in terms of discipline and focus. Furthermore, I am myself a huge fan of good work, and when my students come up with good projects, I’m just completely invigorated by that.

Can you tell us something about the work you’re preparing for the upcoming Biennale of Art in Venice?

Can you tell us something about the work you’re preparing for the upcoming Biennale of Art in Venice?

Well, that aforementioned Second Book is the main contribution for Venice. It is entitled Minutes (as is the entire piece for Venice) — referring to detail, minutae; the passing and accruing of time; and of course, taking meeting minutes, the tallying of progress.

The book as an object is patterned after a calendar/datebook. In considering what one could/should put in an exhibition like Venice, there seemed to be pressure for Big Project, and I sort of dislike the notion of the masterpiece or opus. I like the continuum, that the machine is humming, that things are ebbing and flowing insofar as industry is concerned, and that many factors contribute to the so-called Process. This is most easily evidenced by a glimpse into my own datebook. So, the piece for Venice speaks to that…how my (or the mind) is organized, and what things are in there, and they can be very small things, and that it is something about growth via accumulation. And organization. I like that haircut appointments reside in the same space as big deadlines, and so-called Events of Note.

“Minutes” features work since the Inventory book, and texts I’ve written on them. There is a marvelous essay at the beginning by the author and musician (and my friend) Rick Moody. The publication was designed by the Leipzig-based Markus Dreßen (as was Inventory) and he is simply a masterful talent. Our collaboration is one that I am incredibly proud of.

Minutes, installation view at the Venice Biennale, 2007

Minutes, installation view at the Venice Biennale, 2007

In addition to the publication, which is displayed in a sort of reading room environment, there is an installation of my Trunk Show in the Arsenale. These are a pretty spot-on manifestation of how my work and thought process organize themselves. The idea for this trunk system came from a conversation with my sister a number of years ago. She had visited a 60s submarine-turned-museum in Hawaii, and was extolling the wonders of how the interior worked…the attention to detail, how every little thing had its place in order to economize space, etc. She exclaimed “It was SO Volksboutique!”. I realized that at that time, it wasn’t particularly that any Volksboutique pieces were like this, but that my sister has such a good understanding of how my mind works, that she knew I would identify with this sort of organizational system. And so, the trunks were about making a physical representation of that. They isolate a five day work week into 5 governing tasks (Accounting, Management, PR, Production and Reception) and there are the complete accouterments for each of these occupations in each trunk. They are about economizing space and also rendering these tasks mobile.

Accounting Portable Office

Accounting Portable Office

My Brooklyn studio is right alongside the workspace of Booklyn — a bookmaking artist alliance that I’ve worked closely with since having been in New York. Particularly my friendship and collaboration with Mark Wagner — who manufactured these trunks as over-dimensional, exploded “books” – is important to me, and the show pays homage to that.

Name us 3 to 5 artists whom you think should get more attention from the public.

Well, I will preface this by saying that these are artists I admire and am inspired by, and am lucky enough to be friends with.

But I am not inferring that they are necessarily under-respected or underexposed in any way. But it is certainly excellent if even more people learn about them, because they all do amazing work. I notice that they are all mostly based in New York, which certainly means I need to get out in Berlin more!

Allison Smith (The Muster and Notion Nanny.)

Nina Katchadourian

J. Morgan Puett

Pablo Helguera

Michael Rakowitz.

Thanks Christine!