Cecilia Jonsson, The Iron Ring

Cecilia Jonsson, The Iron Ring

Cecilia Jonsson, The Iron Ring. Photo: Carina-Hesper

Cecilia Jonsson, The Iron Ring. Photo: Carina-Hesper

In the South of Spain runs a river so red and so alien-looking that the Spain tourism board is marketing it as Mars on Earth. NASA scientists even came to the area to investigate the ecosystem for its similarities to the planet Mars.

Due (mostly) to the intense mining for copper, silver, gold, and other mineral in the area, the Rio Tinto is highly acidic, its water has a low oxygen content and it is made dense by the metals it carries in suspension. Its deep reddish hue is caused by the iron dissolved in the water.

Cecilia Jonsson visited the region to collect some of the wild grass that grows on the borders of the Rio Tinto. The name of that grass is Imperata cylindrica. It is a highly invasive weed and its other particularity is that it is an iron hyperaccumulator, which means that the plant literally drinks up the metal in the soil and stores high levels of it in its leaves, stems and roots.

The artist harvested 24kg of Imperata cylindrica and worked with smiths, scientists, technicians and farmers in order to extract the iron ore from the plants and use it to make an iron ring. The innovative experiment brought together the biological, the industrial, the technological and even craft to create a piece of jewellery that weights 2 grams. The project also suggests a way to reverse the contamination process while at the same time mining iron ore from the damaged environment.

While “green mining” aims for a more ecological approach to mining metals, The Iron Ring explores how contaminated mining grounds may benefit from the mining of metals.

Cecilia Jonsson’s mining adventures are detailed in the e-book of the project but i found her investigation into the overlaps between nature and technology so fascinating that i contacted her in the hope that she’d agree to an interview. And lucky me, she did!

Hi Cecilia! I am very curious to know more about the way you, as someone who was primarily trained to be an artist, approach the science/technology side of your projects. Do you typically work with experts to assist you in your research? Or do you just learn the skills and work on your own? Or maybe a bit of both?

My constructions are a combination of hypothesizing outcomes plus trial and error, especially within parameters of biology, physics and technology. Informed by methods used in the natural sciences and empirical material in a site-related context. Mostly they take the form as installation which are the result of intense field work.

The Cuban novelist Alejo Carpentier claimed that the great error of the Surrealists was their own lack of faith: they tried to create the marvelous without really believing in it. “Objects” are often a living metaphor of their own history, their formation. To follow their trace through a wide flow of informative perspectives captures a reverberant relation of objective and subjective distinctions in a sort of intermingled morphology. Built on this quantitative data, the cluster eventually starts to web. When the notion of reality shifts into real it has become a concrete term. Which directs me to sites, material, methods and technologies including disseminated collaborations within other disciplines.

Cecilia Jonsson, The Iron Ring

Cecilia Jonsson, The Iron Ring

Cecilia Jonsson, The Iron Ring. Photo: Carina-Hesper

Cecilia Jonsson, The Iron Ring. Photo: Carina-Hesper

The Iron Ring is an incredible project. You extracted iron from plants and made a ring from what you collected. How did you discover the existence of those iron-containing plants?

Since iron is not the most toxic pollutant, has a low economical and symbolic value and can be virtually scooped up from everywhere, it was tricky to apply the idea to the knowledge base of present-day remediation processes. The research started around five years ago, from my interest for iron in its intrinsic qualities and paradoxical changes. I was looking into experiments of electro-culture, plant communication and how plants can be applied as analytical filters, as a mirroring of their own environment. I found some plants that are more tolerant to iron and are able to grow on this type of contaminated soils. But, most coherent plant studies about efficient iron uptake mostly targeted the human perspective in relation to high organic iron content as an effective adjunct in the treatment of iron deficiency and anemia.

The research was conducted for the project The original arrangement was for a solo violin and a string orchestra from 2012. The installation shows an ambiguous process of an iron hyperaccumulating plant taking up magnetized iron particles that have been scraped of from a reel-to-reel tape of Antonio Vivaldi’s The Four Seasons. On a later stage the iron was extracted again, glued back to the tape and played, resulting in a reinterpretation of The Four Seasons. This work is a predecessor to The Iron Ring were I was interested in taking a more straight functional and site-specific approach to the grass unique ability to extract and encapsulate iron.

The defined iron hyperaccumulating plant with a minimum required amount of 10000 mg/kg Fe revealed in research articles on plant physiology and biochemistry from the university in Madrid. The constructive study had been conducted on the naturalized weed Imperata cylindrica. Collected from the highly acidic (pH 1.6-2) riverbanks of the Rio Tinto in the mining district Rio Tinto in South-western Spain. That model presented me results and a first equation for the calculations of the Iron Ring.

The original arrangement was for a solo violin and a string orchestra

The original arrangement was for a solo violin and a string orchestra

The original arrangement was for a solo violin and a string orchestra

The original arrangement was for a solo violin and a string orchestra

The original arrangement was for a solo violin and a string orchestra

The original arrangement was for a solo violin and a string orchestra

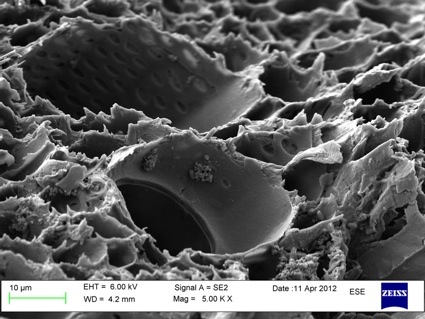

The original arrangement was for a solo violin and a string orchestra. Iron absorption: I. cylindrica, root – Spring concert. Scanning electron microscope: 5.00 KX-10 ?m. Collaboration with; Irene Heggstad and Egil Erichsen at the University of Bergen, Laboratory for Electron Microscopy

The original arrangement was for a solo violin and a string orchestra. Iron absorption: I. cylindrica, root – Spring concert. Scanning electron microscope: 5.00 KX-10 ?m. Collaboration with; Irene Heggstad and Egil Erichsen at the University of Bergen, Laboratory for Electron Microscopy

What was the most challenging aspect in the project? Were there moments you thought it was a mad idea and you’d better give up on it? Or did you know right from the start that everything would go according to plans?

I had actual figures on an expected iron content from the grass in Spain. I knew how to extract iron from organic material and had read about iron reduction and deoxidization processes. It was possible. The next step was to figure out the practical weight of how much bio-ore was actually needed for the process of making a ring of 2 grams. I made some calls to traditionally trained smiths to discuss my idea and I got suggestions on possible processes and an “about” quantity.

The greatest challenge was always the restricted iron quantity to create one ring. The problem isn’t the metal but its proportion of mass (quote). The thin ring is a complex form to cast even with industrial produced iron. Cast iron is very susceptible to loss of metallization at high temperatures, such as the melt temperature required for the cast. A consequence of this is that with each new attempt we made there was a continuous formation of slag and an equal loss of iron. The inclusion of even small amounts of some elements can have profound effects. Because of the impurities in cast iron and its crystalline structure, it is a strong material in compression but weak in tension and very brittle. As a result, when it fails, it does so in an explosive manner, with little warning.

Cecilia Jonsson, The Iron Ring

Cecilia Jonsson, The Iron Ring

Exhibition of The Iron RIng at V2_ Rotterdam, The Netherlands. Photo; Jan Sprij

Exhibition of The Iron RIng at V2_ Rotterdam, The Netherlands. Photo; Jan Sprij

The project starts with humble plants and end up with a tiny little ring. But what I found amazing was the amount of craft, heavy industrial processes and knowledge required to go from plant to ring. What have you learnt about the flow of organic matter while working on the project?

From working with iron as material, the matter itself as well as on its interaction with the living. The Iron Ring has really broadened my understanding of the complexity of ecosystems. From the field to the laboratory-scale to craftsmanship and industry, I have had a proper opportunity to build collaborations with proficiency on a wide scale. Their engagement to think out of the box and the connectedness to sort of re-invent and re-discover iron production in our industrial age, has really made a strong impression.

The Iron Ring also highlights the toxic impact of mineral exploitation on the environment. However, you write in the description of the project: “The result is a scenario for iron mining that, instead of furthering destruction, could actually contribute to the environmental rehabilitation of abandoned metal mines.” Could you elaborate on this rehabilitation of the abandoned mines? How would that work? What would it be like?

The abandoned mines in Rio Tinto are a no man’s land. Apart from tourists who come to visit the unworldly sites, the area continues its forgotten glory to slump and erode. Rio Tinto has a dark, long history of being exploited for ferrous and non-ferrous minerals, copper, gold, silver and lead and due to its historical perspective the rightful ownership of the excavated mess is undefined and beyond present laws of remediation. To stabilize or reduce contamination of sites like Rio Tinto, you first need to analyse the soil and from that result, plant several different types of hyperaccumulating and tolerant green plants.

The project elaborates on this possibility to utilize the cleansing process of the naturalized grass, which overlooked ability is left unutilized. The project proposes to harvest the grass for the purpose of extracting the ore that is inside them. The idea of the ring is to complete the circle, to maintain the clean-up commitment. So that when the soil is stabilized, other native plants can be introduced to restore the biodiversity and help bring back the heritage of flora that was lost through the human activity.

There are many layers behind the “rehabilitation” statement. Which under controlled conditions could include the naturalized grass: Imperata cylindrica in a remediation process where its biomass is utilized for iron production. A larger harvest would also contribute to less complications and a more refined iron production with less slag and more iron in just two steps. Going back to the complexity of ecosystems and my second connotation of the “rehabilitation”. Which is to utilize the already inhabited weed to be able to control its spread in the environment. Imperata cylindrica is an aggressive fast-growing perennial grass that can and has become an ecological threat. It’s listed as one of the ten worst weeds in the world and is placed on the U.S. Federal Noxious Weed list, which prohibits new plantings. The grass does not survive in cultivated areas but establishes along roadways, in forests and mining areas, where it forms dense mats of thatch that shade and outcompete native plants.

The enigma of use- and exchange-value enchants me as well as the perspectives on precious matter and how it earns its cultural weight. Something that I think Ralph W. Emerson beautifully formulates in What is a weed? A plant whose virtues have not yet been discovered. A metal is deemed to be precious if it is rare and on account of its material nature and rarity, the high value is linked to its cost of extraction.

How long did the whole process take? From the moment you found the plants to the final realization of the ring?

From when the first plant community was found in Spain to the ring had become one continuous solid, 5 weeks of intensive work.

Stratigrafi

Stratigrafi

Stratigrafi

Stratigrafi

Stratigrafi

Stratigrafi

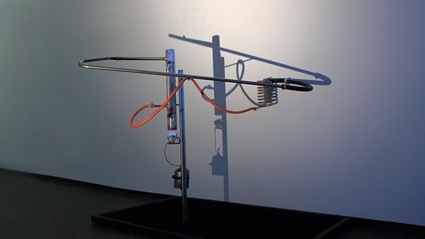

Could you explain what we can see in the photos of the installation Stratigrafi? What is the strange metallic sculpture?

Stratigrafi is a work developed in collaboration with colleague Signe Lidén. Thematically, we were exploring cavities, man-made places and fundamental changes of the landscape. Exploring the mine as an in-between space a geographical cavity between nature, ideas and technologies and how history works way through its forms. Signe had been in Kakanj in central Bosnia and Herzegovina and Bytom in Poland to explore coal mines. I had gathered material in relation to iron from re-vegetation institutes and large-scale surface mining in the region of the Iron Quadrangle, southeast Brazil. The installation intertwined our works where one was taken inside and introduced to impressions from these places. Representations, imitations, scent, recordings, objects and photographs from the sites.

The metal sculpture is a propane driven apparatus, a citrus distiller. The steam was forced through the citrus material and transported onward through the condenser where the temperature is lowered and consistently forms refined acidic drops and erosion. In the windows scorched wood were piled up and filling the room with intense scent. A video without sound projected an exotic landscape in one meeting with passing carts filled with iron ore. The light table consisted of oscillating reversal film, archive material, seeds, a small projection and an exhibition text written by Roar Sletteland. The visitor obtained an auditory access to these sceneries by putting their heads into listening boxes.

Water extraction, Geneva – Rhône: 02.11.2009 / Rain: 02.11.2009 / Arve: 02.11.2009

Water extraction, Geneva – Rhône: 02.11.2009 / Rain: 02.11.2009 / Arve: 02.11.2009

Water extraction, Geneva – Rhône: 02.11.2009 / Rain: 02.11.2009 / Arve: 02.11.2009

Water extraction, Geneva – Rhône: 02.11.2009 / Rain: 02.11.2009 / Arve: 02.11.2009

I’m also fascinated by the work Water extraction, Geneva. The work seems to be about global warming. Could you explain the installation?

Water extraction, Geneva – Rhône: 02.11.2009 / Rain: 02.11.2009 / Arve: 02.11.2009 was a site specific work consisted of three water extracts, three modified found light bulbs and one light sourced bulb. For the installation, the wooden planks in the floor of the exhibition space were removed, uplifted and were then used to create a platform and a bridged island to the work.

The work looks at the impact that climate change is having on the glaciers and the changes it brings with it. A glacier is important for freshwater storage, while glaciers also can be regarded as reservoirs for the production of electricity through their seasonal water flow. The project focuses on the melting of the Rhone Glacier in Switzerland, which over the past ten years has lost 6% of its mass. The raising temperatures in the region have a strong influence on the seasonal runoff regime of the alpine streams. Where the Rhone glacier runoff with the residues it brings with it, is the main water source for the largest freshwater reservoir in Europe, Lake Geneva.

You are currently in Venice for a residency at the Fondazione Bevilacqua La Masa. What are you working on over there? What is the residency about?

It’s a three months residency from February to mid May supported by the Office for Contemporary Art Norway. I’m here to develop a new work, a hydrodynamic analogy that acoustically transcribes an interdependent exchange between external forces and internal positive feedback. The Venice lagoon is a delicately balanced natural system that combines to produce one of the largest wetlands in the Mediterranean. Land and water are intermingled. An urban Lagoon, a natural Venice as Marcel Proust captures the reverberant paradox relationship. The project explores the Venice Lagoon’s sedimentary environment, its dynamics and composition and is developed in collaboration with the University of Padova at the Hydrobiological Station in Chioggia in the Veneto region.

Any other upcoming exhibition, research or project you could share with us?

After Venice, I will be in Helsinki for a collaborative project on magnetotactic bacteria as part of my participation in a research platform for Art and Synthetic Biology at Biofilia, Alto University. In the fall I will undertake a three-month’s residency in Marseille at Triangle France. Let’s say there are a few larger research projects under development and works that are more in the making for planned venues.

Thanks Cecilia!

The Iron Ring was made possible through the support of Production Network for Electronic Art, V2_ Institute for the Unstable Media and the Arts Council Norway.