Data Cuisine goes against everything i’ve learnt as a child: Don’t play with food! Don’t mix meals with political discussions! In these workshops, participants experiment with the representation of data using culinary means. I suspect they are even allowed to put their elbows on the table.

The workshop invites participants to translate local data into culinary creations, turning arid numbers into sensually ‘experienceable’ matter.

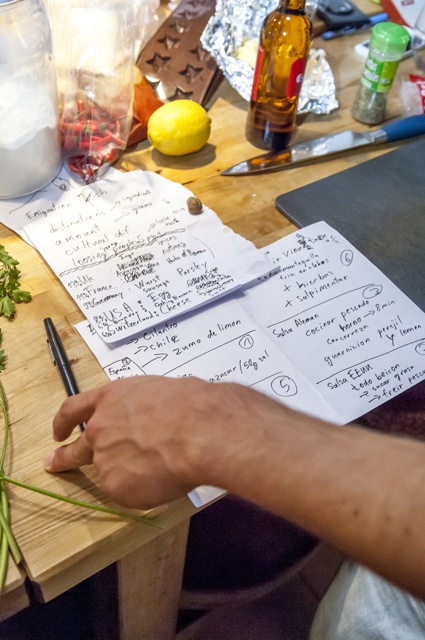

Participants chose their topics, investigate related data, shop for comestible ingredients and under the guidance of chefs, they learn how to create dishes that will not only be delicious but also act as entry points to discussions about local issues that range from emigration to criminality, suicide rate, unemployment, sexuality or science funding.

There’s been two editions so far. The first one was the Open Data Cooking Workshop in Helsinki. And the latest was a Data Cuisine Workshop that took place last month in Barcelona.

I had a quick online chat with the creators of the workshops, data visualizer Moritz Stefaner and curator Susanne Jaschko from prozessagenten, process by art and design.

Samuel Boucher & Jahn Schlosser, Emigration Fish

Samuel Boucher & Jahn Schlosser, Emigration Fish

Antonija Kuzmanic, Requiem for Science

Antonija Kuzmanic, Requiem for Science

Rossana Moroni preparing a Suicide Cocktail

Rossana Moroni preparing a Suicide Cocktail

Hi Susanne and Moritz! Seen from the outside, the idea is somewhat simple: just take some data and assemble them on a plate instead of a graph, use culinary ingredients instead of lines and block of colours. Yet, i suspect the process must be more complex than that. What are the challenges participants encounter when trying to turn numbers into dishes?

SJ: It might sound simple, but cooking and data visualisation or representation are two very different disciplines. Food is sensual, tangible, ephemeral, emotional and social. Data is not like this at all. This dialectics is the starting point of the Data Cuisine workshop and for someone who has never done it, it is already a challenge to think both together and to play with the various qualities of food such as its cultural connotations, colour, taste, shape, nutrition and the range of techniques to prepare food such as melting, freezing, boiling, baking, foaming…Not to speak of the various ways one can present and consume food.

Actually there are so many possibilities to explore on both ends, the data and the food, that most participants end-up with something relatively simple, because they are overwhelmed by the complexity. A translation of data into a visual edible diagram is relatively easy, but that’s not what we are striking for, but for creations that work and communicate on both levels, visually and as regards taste.

One of the questions the workshop asks is “Have you ever tried to imagine how a fish soup tastes whose recipe is based on publicly available local fishing data?”

One of the questions the workshop asks is “Have you ever tried to imagine how a fish soup tastes whose recipe is based on publicly available local fishing data?”

So does data affect taste and how? For example, do you have to make concession and be a bit less respectful of data to ensure that a dish is delicious?

MS: Generally, when it comes to tasting precise quantities and differences, of course, our taste organs are more limited than our visual system. It is simply much harder to determine what is “twice as sweet” as opposed to as twice as long line in a graphic. Then again, taste is a much more emotional and temporally complex experience that just looking at a dot on a screen. So, the mechanisms to encode information might be more fuzzy, but potentially much deeper.

Depending on the theme, there could also be a case to be made for dishes that don’t taste all that well (like, e.g., the noise visualization through salt).

In the end, our goal is to create eating experiences that teach you something about the data, and taste is one dimension you can vary, but there is also temperature, texture, amounts, the plating, all the cultural connotations different dishes and ingredients have … all this plays together in creating a successful dish. Here, precision of data readability is not of primary concern, but rather, the overall personal experience, and the dishes’ concept.

Can any data be turned into something edible? Or did participants find themselves in front of data that when cooked together could only lead to unpleasant flavors?

Can any data be turned into something edible? Or did participants find themselves in front of data that when cooked together could only lead to unpleasant flavors?

SJ: We ask the participants to work with local data, ideally open data, and the experience from the two workshops shows that most people tend to pick data that reveal social and economic problems. This is not really surprising as we encourage people to pick a topic that they feel close to, that motivates them to work on, and to turn it into some kind of food experience. Creating a dish that tastes terrible is sometimes the best way to communicate a negative development or a problematic situation. Good examples for this are the ‘Suicide Cocktail‘ that looks at the relation of alcohol consumption and suicide rates in Finland and ‘Unemployed Pan con Tomate!‘ that visualises the drastic increase of unemployment among young people. We tell participants that they should decide early on, if they want to be that radical or if they want to try something that is more subtle and comparably more difficult to produce.

You work with chefs in each of these workshops. How do they intervene? What exactly is their role in each workshop?

SJ: The chefs are very important, when it comes to creating the dishes. In most cases, a ‘data’ dish is created by either remixing, altering or re-interpreting existing recipes. The group of participants is usually very heterogeneous and have different professional backgrounds. However, they all have an interest in cooking or at least in doing something with food, but some are knowledgeable than others. The chefs bring the real cooking expertise to the table. Usually our participants quickly develop ideas what they want to do and which dishes they want to create, and then it’s the chef who — with his or her experience and creativity — pushes them to open up their mind, to try something new and unusual, such as trying out other techniques or ingredients. When we are in the kitchen, the chef is in high demand, not only for the preparation of dishes, but also for their final presentation on the plate.

So far you’ve organized 2 Data Cuisine workshops. One in Helsinki and one in Barcelona. These are two very different kind of countries in terms of cuisine. Do you feel that participants approached the idea of mixing data and food differently? Because i somehow feel that a lot of personal culture and subjectivity enters into account when dealing with food.

So far you’ve organized 2 Data Cuisine workshops. One in Helsinki and one in Barcelona. These are two very different kind of countries in terms of cuisine. Do you feel that participants approached the idea of mixing data and food differently? Because i somehow feel that a lot of personal culture and subjectivity enters into account when dealing with food.

SJ: In Helsinki less of the dishes were local, maybe also due the fact that a lot of Helsinki workshop participants were either immigrants or just visiting. I remember that Moritz and I were wondering what constitutes Finnish cuisine before we had our first meeting with Antti Nurka, the Finnish chef. And it was particularly interesting to see how the shortage of vegetables that grow in Finland and the variety of local mushrooms, berries and fish influence the Finnish menu. But other than that I couldn’t discover much differences in the general approach of the participants, maybe because the people who join the workshop are usually food-aficionados.

Domestic Data Streamers, In & Out

Domestic Data Streamers, In & Out

I think what i like about this workshop is that it breaks a taboo for me. I grew up being told that you don’t mix politics and food, that you can’t talk about sensitive or potentially divisive topics while having a meal. Yet, many of the projects were directly related to politics and social issues. Besides, one of the objectives of the workshops is precisely to merge food with data in order to “gain unexpected insights into both media and learn about their inner constructions and relations”. So what have you learn so far about these constructions and relations?

MS: From a data visualization point of view, I found it really interesting to watch how deeply people meditate on very simple data points, when they think about turning them into food experiences. In a way, this is a very needed counterpoint to the current trend of consuming lots of data in a very quick and superficial way. As Jer Thorp said, “we are so used to flying at 10,000 feet that we forget what it is like to be on the ground” and both the preparation and consumption of the data dishes providesa very earthy, grounded way to connect with statistical information and the human stories behind the numbers.

From a food point of view, knowing how expressive food is as a medium, it is surprising to me by now, how little the intellectual side is stimulated in high-end cuisine. It is surely nice to just enjoy interesting tastes in good company, but it can also be quite enriching if there is a whole extra conceptual and intellectual dimension to the dining experience. I think this side has been quite neglected in the history of cuisine and we are hoping to provoke a few reactions in — and hopefully some inspiration to — the traditional cooking scene.

What’s next for Data Cuisine?

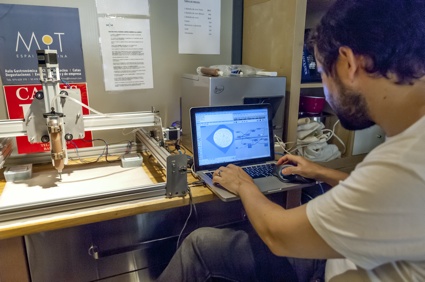

MS: We aim for a few more editions of the workshop, in order to understand the local differences better and continue to explore the medium. We might also vary the format in the future – one format we were considering is a high-end “data dinner”, which would put less emphasis on the collaborative workshop process, but more the final outcome and dining experience. And I would like to learn more about the science of cooking and the technological advances in the area – this field is buzzing right now!

Thanks Susanne and Moritz!

All images courtesy of Data Cuisine. More photos.