And now for something completely different….

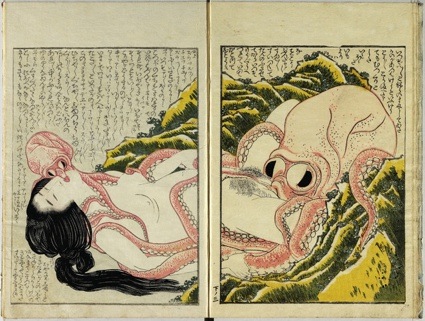

Katushika Hokusai , Diving Woman and Octopi, 1814). This woodblock print image borders on the surreal. Source: Micheal Fornitz Collection via Bloomberg

Katushika Hokusai , Diving Woman and Octopi, 1814). This woodblock print image borders on the surreal. Source: Micheal Fornitz Collection via Bloomberg

Last Thursday, i stopped at the British Museum to see Shunga: sex and pleasure in Japanese art. I thought that Thursday would be a good day for a quiet visit. Wrong! It was the kind of crowd in which you have to stretch your neck in unnatural directions to read the descriptions of the works and wait patiently behind several people before you can actually approach a print. When finally you’re in front of the work and have had a good look, you want to turn and walk to the next window but you’re blocked by the people waiting and staring behind you. And no, they won’t move lest they loose their spot in the queue.

My visit was thus laborious but i liked the show so much i’ll have another try (a Tuesday morning when the doors open? a lunch time?)

Produced in Japan from 1600 to 1900, Shunga (or “picture of spring”, spring being an euphemism for sex) are erotic paintings, prints and books that were used for personal stimulation and for the education of young lovers.

Make no mistake: this was art, not what we’d now call “pornography”. In fact, the works were regarded as a suitable gift to brides on the eve of their wedding or to official foreign visitors. Unaffected by the inhibited sexual attitudes of Christianity or Islam, Shunga presented a fantasy world of sexual delight enjoyed by both sexes. The sense of sin didn’t have a place in shunga. But female pleasure, tenderness and beauty did.

The genre flourished even when it was officially banned and many works were in fact produced by some of the country’s most distinguished artists. The decline of shunga is attributed to the arrival of Western culture and technologies at the end of the 19th century and in particular the importation of photoreproduction techniques. How could Shunga compete with erotic photography?

In Japan, however, the influence of shunga can still be seen in manga, anime, tattoo art and other popular cultural forms.

I got the following photos from the British Museum press office. Unsurprisingly (but disappointingly), the ones i received were quite tame compared to most of what you can see in the show:

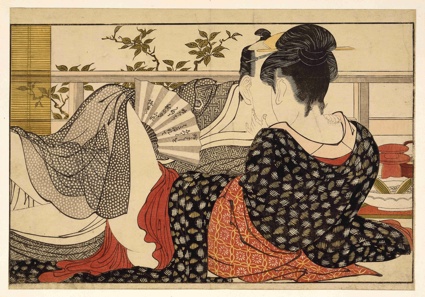

Kitagawa Utamaro; Mare ni au koi 稀ニ逢恋 (Love that Rarely Meets), c. 1793-1794 © The Trustees of the British Museum

Kitagawa Utamaro; Mare ni au koi 稀ニ逢恋 (Love that Rarely Meets), c. 1793-1794 © The Trustees of the British Museum

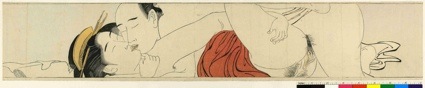

Torii Kiyonaga, Sode no maki (Handscroll for the Sleeve), c. 1785. © The Trustees of the British Museum

Torii Kiyonaga, Sode no maki (Handscroll for the Sleeve), c. 1785. © The Trustees of the British Museum

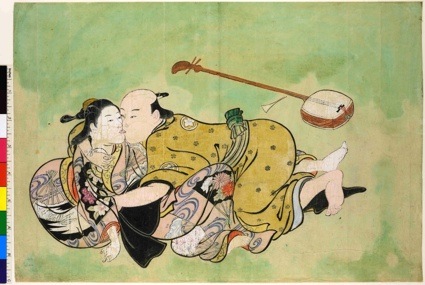

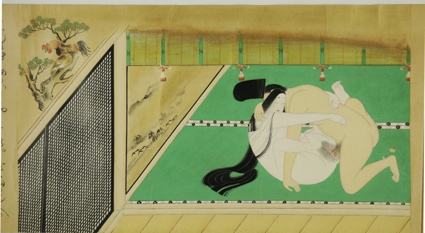

Nishikawa Sukenobu, Sexual dalliance between a man and geisha, c. 1711-1716. © The Trustees of the British Museum

Nishikawa Sukenobu, Sexual dalliance between a man and geisha, c. 1711-1716. © The Trustees of the British Museum

Kano school. Older and younger man making love, first scene from Untitled shunga handscroll. Early 17th century. The British Museum, purchase funded by Brooke Sewell bequest

Kano school. Older and younger man making love, first scene from Untitled shunga handscroll. Early 17th century. The British Museum, purchase funded by Brooke Sewell bequest

Hosoda Eishi, Contest of Passion in the Four Seasons (Shiki kyo-en zu), late 1790s-early 1800s; one of a set of four hanging scrolls

Hosoda Eishi, Contest of Passion in the Four Seasons (Shiki kyo-en zu), late 1790s-early 1800s; one of a set of four hanging scrolls

Attributed to Sumiyoshi Gukei and Takenouchi Koretsune. Series title: Tale of the Brushwood Fence, 17th century

Attributed to Sumiyoshi Gukei and Takenouchi Koretsune. Series title: Tale of the Brushwood Fence, 17th century

Shunga: sex and pleasure in Japanese art is at the British Museum, until 5 January 2014.