A few weeks ago, i was back in Gijón for the opening of Elastic Reality at the Laboral Art Center. The show looks at how artists are representing, commenting on and reacting to the shift in our understanding of the world brought about by technical innovations and in particular by our permanent state of ‘connectedness.’ I’ll write with more details about the exhibition in the coming days but right now, i wanted to bring the spotlight on a work i found particularly impressive and thought-provoking.

In Tarnac. Le chaos et la grâce, Joachim Olender explores a police and judicial blunder that hit France in November 2008 when a group of policemen wearing black balaclavas stormed into the small village of Tarnac and arrested a group of people who were later accused of being far-left terrorists plotting to overthrow the state.

Police swooped on Tarnac at dawn and arrested four men and five women, aged 22 to 34, over terrorist claims. Photograph: Thierry Zoccolan/AFP/Getty Images (via)

Police swooped on Tarnac at dawn and arrested four men and five women, aged 22 to 34, over terrorist claims. Photograph: Thierry Zoccolan/AFP/Getty Images (via)

Known as the Tarnac Nine, these people were in particular accused of incidents of vandalism on France’s high-speed railway lines, which caused delays but no casualties. The case was characterized by a lack of proof against the ‘terrorists’. The whole case against them was built on two things. The first was that the ‘ringleader’ Julien Coupat and his girlfriend had allegedly been seen by police near a train line that was later vandalised. The second one was an anonymous tract against capitalism and modern society titled The Coming Insurrection which the police believed was authored by Coupat.

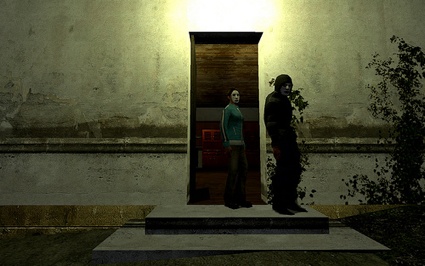

Joachim Olender’s explores the affair through a set of a video-installation and an animaiton film. In one room, three screens hanging side by side show the images that the artist took on the ‘scenes of the crime’ and these images are pretty unspectacular: empty landscapes, desolate roads, farms in Tarnac, railways and dirty snow. A small room contains the second part of the installation: an animation film charting the various episodes of the affair, from the arrest to a discussion in the French Parliament. In the animation, the Tarnac Nine are wearing masks, they never utter a word and move quietly.

Joachim Olender, Tarnac

Joachim Olender, Tarnac

Joachim Olender, Tarnac

Joachim Olender, Tarnac

I found the project very moving. The story of the Tarnac Nine was obviously gripping, especially as i discovered it right when i was watching the final episodes of the TV series Spiral which was also dealing with social revolutions, acts of sabotages and the far-left in its various guises. But the way the artist dealt with the issue was also clever: he set the pace, exposed what have been called ‘the facts’ but let us draw our own conclusions. There’s an air of mystery, an ambiguity that kept me glued to the installation’s screens.

That’s why i wanted to interview the artist and in case you’d rather read his answers in original language, you can scroll down and read Joachim’s answers in french.

Hi Joachim! Why did you decide to explore the Tarnac affair? Why this particular story?

The first image i recall evokes an American blockbuster. The headline of Libération on December 3, 2003 was Tarnac, des terroristes vraiment? (“Tarnac, are they really terrorists?”). You see men wearing black balaclavas storming into a village. There were talks of terrorism everywhere so i assumed they were terrorists. Later on, I realized they were cops. But i found the confusion striking and it stayed with me ever since.

I starter collecting all the articles i could get my hands on. There was something peculiar that bothered me in this affair, I just didn’t know what it was exactly. But my intuition told me that I needed to dig deeper into the story. Time passed, I worked on other projects and I came back to it in the Summer of 2011.

I was stricken by the unresolved issue, the dark stain right in the middle of the photo, the one that conceals a crucial element, the one that prevents the case to be closed and that builds up a myth instead.

Everything brought me back to a fiction, a story that needed to be told in order to expose its absurdity. I had the feeling that there was material, a breeding ground for reflection but above all, there was a dimension i could not grasp, a dimension that would not be grasped. The more i delved, the more obvious it was to me that the investigation was futile. It wasn’t that the truth (the legal truth, the truth of the facts) couldn’t be proved. To me, the issue was elsewhere. There were elements in the story that prevented me from moving on and that gradually made their roots into my projects, to the point of becoming its very core. Like a trick, an ambush that would become the making and the re-making of the affair. And of my film.

View of the exhibition at LABoral. Photo LABoral/Marcos Morilla

View of the exhibition at LABoral. Photo LABoral/Marcos Morilla

Can you tell us about the material you used to research, document, prepare the installation? Did you meet some of the protagonists? Use mostly information found in mainstream media?

The issue of the sources is probably the one that matters the most to me. In 2008, a few months before the arrest of these young people in Tarnac, a very engaged philosophical and political essay titled “L’insurrection qui vient” (The Coming Insurrection) authored by an invisible collective. People in power got scared by that book and decreed that the authors were young “anarcho-autonomous” people from Tarnac. They pointed to links between extracts from the book and the sabotage of TGV (high-speed train) lines and attempted to claim that these acts of sabotage were in fact acts of terrorism.

In other words, the book was a bomb and its authors were terrorists. There were also plenty of press articles about the affair, many of them were published in Mediapart. I was reading everything i could get my hands on. I remember one article in particular: Pourquoi l’affaire de Tarnac nous concerne tous (“Why the Tarnac Affair matters to all of us.”) It was written by Edwy Plenel (the President of Mediapart) on April 25, 2009. He explains with great clarity (a rare occurrence in this affair) that the issue with the Tarnac affair was the violation of vital democratic principles and that it should matter to each of us, even if and especially if we didn’t agree with the ideas brought forward with the main protagonists.

That was precisely what needed to be told.

No matter what they were thinking, what they had written and even no matter what they had done, as long as their guilt had not been proven, they were entitled to the presumption of innocence. Strangely enough, what was important to me what not so much to figure out whether they were guilty or not. But the problem is that once the presumption of innocence is violated, it’s too late and those in power have won because in people’s minds, these guys are guilty.

I later got in touch with David Dufresne, a former journalist who had followed the Tarnac Affair for Mediapart. At the time, in November 2011, he was finishing his book “Tarnac, Magasin général” (Tarnac, General Store.) I wrote him a long email, i wanted to submit my twisted vision to someone who had a good understanding of the affair. I needed to know whether i was completely mistaken or not. Everything was quite confusing at the time. And that’s probably this chaos that i found so compelling. I found it totally unreal.

Reading Dufresne’s book taught me a lot about the affair. At the start of the affair, in late 2008, i read the texts and essays authored by the Tiqqun collective but often attributed to the Invisible Committee, the authors of The Coming Insurrection.

I didn’t want to interview the protagonists and enforce their desire of discretion. But i wrote them, to say that i was coming to Tarnac and that I would have liked to meet them. They confirmed my intuition by answering that they’d rather remain in the shadow. While i was there, i met one of the defendants. We said we’d meet again to talk. But then it snowed so much, it was so cold. I never saw her again.

That’s it for the sources. I should add that, although I was originally trained as a lawyer, i became an artist. Unlike the lawyer or the journalist who follows an affair, i can chose to feed exclusively on confusions, incoherence, gaps, cracks and on my own intuition. Instead of using what appears, i exploit what doesn’t appear. Since nothing was clear in this affair, i decided to produce my own archives. That’s why the virtual film is a document like any other document, although it has been built from scratch. It reveals the deception as much as it conveys the essence of the affair: the reconstitution. My film and installation became secondary sources. So while i was revealing the deception, i was also contributing to it and keeping the myth alive.

Another thing: i wrote a scenario, based on ‘real facts.’ And i say ‘real facts’ because that is where the impossibility of telling the story started. Facts are inherently real but, in the Tarnac affair, every single element seemed to be debatable. To the point that my documentary project was, right from the start, distorted. Nipped in the bud. So this impossibility was what i worked on. No evidence, no trace, nothing. Just books. And that’s fundamental, the main source used by the government, the one they regarded as ‘evidence’ was a book.

Joachim Olender, Tarnac

Now i’m also curious about the form that the installation takes. First, there’s a 3 screen installation showing images you shot on location. And in an adjacent room, video game images chart the whole affair in complete silence, with members of the Tarnac Nine wearing masks. Why did you chose to show explore the subject this way? Why are the protagonists silent? Why using both videos of the location and virtual images?

I wanted to fragment. The double installation sets a kind of mirror. I wanted to create an off-camera, separate the points of view. Each film is the counterpart of the other one. On the one hand, there’s what appears to be real. On the other one, the virtual. Whichever reality we choose to see remains amputated. It’s as if neither of the videos was sufficient to tell the story but the only thing that could account for this was the double installation itself, its fragmentation, the division between the materials: the real and the virtual.

The working process was laborious. Each step, which had to fit into the project, acted as a basis for the following stages. I went shooting in Tarnac and Dhuisy (the location of the sabotage) with my cameraman and the editor who, because i couldn’t afford to hire a sound engineer, had accepted to undertake the sound part as well. The idea was to make a “movie without a trace.” I wanted to show the location of an affair that had shaken France. The places were obviously empty… The words of the accused had to be superposed to these images. I used extracts from the essays that were attributed to them as well as the superb interview with Julien Coupat (the main suspect in the Tarnac Affair) that was published in Le Monde on 26 May 2009, while he was still in prison where he would be detained for 6 months. Adding a voice-over was a way to confront the viewer. Because of the chaos, it was important to articulate certain things. You can always beat around the bush but the only things that seemed ‘real’ to me were their own words. They had to be heard. If you stay put and listen to the words, you are bound to ask yourself questions, it’s a ‘matter of sensitivity’ (dixit Julien Coupat.)

The making of the video game was the most important part. During five months, i worked in Garry’s mod, a video game software, with two 3D animators. Using my footage and the images from Google Earth, we made a reconstitution of Tarnac and Dhuisy. I wanted to make a film you didn’t know how to enter. Just like in Waltz with Bashir by Ari Folman, i felt that only animation could convey the real. The ideal suspect would be in place but nothing would happen. No action nor crime. Nothing. Only the direction would suggest the action. Twisting the video game universe, diverting it, hijacking the bugs, the constraints, the impossibility to manipulate the characters as one would wish, all these elements build up a kind of strangeness.

The peculiarity is that it was a real “virtual shooting.” I placed the cameras inside the sets built with my graphic designers and I filmed the models of the characters. I worked shot by shot rather than frame by frame. My approach is thus, on this aspect, closer to cinema than to animation.

The idea of the mask came out of the anonymity of the protagonists. It was part of their ideology. The Invisible Committee wrote in The Coming Insurrection that “Being invisible is to be exposed.’ They hardly ever accepted any interview. They were distrustful. Even when he was released from prison, Julien Coupat was in the truck of a car, to avoid meeting the press. Appearing in the case meant entering the political arena and the ‘society of the spectacle.’ The masks made them anonymous as much as it made them suspects. Besides, masks turned them into characters of the Commedia dell’arte. They had ended up in the spotlight and despite themselves, they kept the myth alive. Finally, it was also a way to play with the codes of the video game. The fact that everyone, the heroes and the villains, were wearing masks added to the general confusion in the film. I wasn’t convinced of their innocence but it didn’t matter to me anymore. However, i was convinced that the law had been violated. Even if the book had displeased those in power, that didn’t make these guys terrorists. So I staged the abnormality, the fear, the figure of the guilty one, with a certain dose of irony so that viewers would ask themselves “But are they really guilty?” “What have they done exactly?”

The silence of the protagonists, just like the mask, plays on the ambiguity. It erases any trace of culpability while raising suspicion at the same time. Besides, this reflects the “truth” quite accurately since the defendants have almost never expressed themselves in this affair. That might have driven the government crazy. And that’s probably what ‘saved’ them. But the voice-over of the triptych was devised to echo the animation film. Even if they don’t have a face, their words are present, their texts haunt the film.

Joachim Olender, Tarnac

Joachim Olender, Tarnac

Joachim Olender, Tarnac

Joachim Olender, Tarnac

While working on this interview, i’ve been reading about the Tarnac Affair and trying to figure out where the “Tarnac Nine” are nowadays, if they have been cleared of the accusations, etc. But i couldn’t find any satisfying answer. Information seems to stop in 2010. Has the State and the police formally apologized for the unjustified accusations? And what does the general public think? Do they still believe that the protagonists are guilty or is it now clear to everyone that there was little to no evidence to sustain the accusations?

I don’t know the current legal situation of the defendants but i do know that these young people from Tarnac have long been (up to the time i was making the film at least) forbidden to leave the country and under judicial supervision. The situation is moving gradually. In November 2011, after the Tarnac Nine had accused the counter-terrorism police to have fabricated a counterfeit statement, the prosecutor of Nanterre opened an investigation for “forgery and use of forgery of public documents.” In March 2012, the counter-terrorism examining magistrate, Thierry Fragnoli, is removed from the case. And on 24 October 2012 (four years after the start of the affair!), the newspaper Le Canard Enchaîné revealed that the credit card of Yildune Lévy, girlfriend and later on wife of Julien Coupat, had been used in Paris in the night of the 7th to the 8th of November 2008. Thus far away from Dhuisy, where the sabotage took place. The bank statement reports a withdrawal of 40 euros in Pigalle at 2.44am. Two days later, the Versailles Court of Appeal ordered the hearing of 18 policemen who had participated to the surveillance operation of the members of the Tarnac group. And, on 12 November 2012, Julien Coupat finally broke his silence and accepted to answer questions from journalists. “From now on, the only way we can disappear is by appearing,” he explained. I’m not aware whether justice has pronounced a dismissal of the case.

As regards public opinion, i think it has evolved over the course of the affair. For the first three years, at the exception of Mediapart, only very little alternative information was published. I believe that unfortunately, when the press follows those in power and violates the presumption of innocence, people engulf themselves in that direction too. Libération, a newspaper widely regarded as ‘left-wing’ headlined “L’Ultra gauche déraille” (The Far-Left goes off the rails), they later changed their position but by then it was too late. I think that many people believed they were guilty. Especially because, as I explained earlier, the defendants themselves contributed to the mystery. By refusing to appear, for example.

Since the launch of the book “Tarnac, Magasin Général”, the election of François Hollande and the latest legal elements of the case, the police blunder seems to be confirmed. But I doubt that the majority of the people really care.

As i said earlier, before choosing art, i studied law. It is clear that the question of the criminalization of ‘terrorism’ has concerned me a lot. Let’s remember that the ‘terrorists’ of 1940 were regarded as hero after the Liberation. But you know, everything is connected. In a case like this one, you cannot chose on side and leave another one aside. The rest is just a matter of communication. I think that the viewer understands better when they do they own reasoning. They have to be free to understand.

There’s this really interesting essay written in 2009 by Alberto Toscano for The Guardian. He argues the Tarnac Nine has demonstrated that we are losing “the political literacy, and the legal capacity, to distinguish between sabotage and terrorism, vandalism and mass murder, as every oppositional alternative to the status quo is swallowed up under the umbrella of terrorism. ”

Was your work commenting on this kind of issue? Or did you want spectators to draw their own conclusion?

I wanted to highlight the absurdity of an affair that was built upon the publishing of a book. The criminalization of thought is a nightmare beyond understanding. It is pure literature (or, as you wrote, it is now worthy of a tv series.) It is Kafka’s The Trial, George Orwell’s 1984, it is science fiction. In Minority Report, Philip K. Dick imagines a society that hunts ‘pre-crime’, the crime before it has even been committed. Only fiction could make people reflect. Paradoxically, people regard it as a documentary work. But i wrote a screenplay based on facts that were entirely reinterpreted. What else was I supposed to do? What is real, apart from the books that i read and the mounting of a case no one knows anything about? The absence of traces or the way to create archive using fiction: that’s the whole issue. What can you see in virtual reconstructions, in a video game? A piece of evidence? An archive?

Thanks Joachim!

Credits: scenario and direction of the animation film: Joachim Olender. Production: Le Fresnoy + Solilok asbl. 3D animation: Thomas Jorion and Alexis Fradier. Editing of the image: Yannick Leroy. Sound editing: Yann-Elie Gorans. Mixing: Simon Apostolou ; Calibration: Baptiste Evrard

Scenario and direction of the triptych: Joachim Olender. Production: Le Fresnoy + Solilok asbl. Voice-over: Soufian El Boubsi. Music: Pierre Hujoel. Image: Vincent Pinckaers. Sound: Yannick Leroy. Editing of the image: Yannick Leroy. Sound editing: Yann-Elie Gorans. Mixing: Simon Apostolou. Calibration: Baptiste Evrard.

————

Now for the answers in french:

Why did you decide to explore the Tarnac affair? Why this particular story?

La première image dont je me souviens est celle d’un blockbuster américain. Le Libé du 3 décembre 2008 titrait “Tarnac, des terroristes vraiment?”. On voit des mecs avec des cagoules noires qui débarquent dans un village. On parlait de terrorisme à tout bout de champ, j’ai donc pensé que c’était les terroristes. Ensuite, j’ai compris que c’était les flics. Mais cette confusion m’a marqué, et elle m’est restée.

Je me suis mis à collecter tous les articles que je trouvais. Il y avait quelque chose de particulier qui me préoccupait dans cette affaire, sans savoir quoi au juste, mais j’avais l’intuition qu’il y avait quelque chose à creuser. J’ai laissé passer du temps, j’ai travaillé sur d’autres projets et j’y suis revenu à l’été 2011.

Ce qui m’avait interpellé, c’était la question non résolue, la tache sombre en plein milieu de la photo, celle qui dissimule un élément crucial, empêchant toute résolution de l’affaire et construisant, à la place, un mythe.

Tout me ramenait sans cesse à une fiction, une histoire qu’il fallait raconter afin d’en relater l’absurde. J’avais la sensation qu’il y avait là une matière, un terreau de réflexion mais surtout il y avait une dimension qui m’échappait, qui était là comme pour m’échapper. Plus je m’y plongeais, plus l’impossibilité m’apparaissait évidente et rendait à mes yeux l’enquête vaine. Non qu’il fut impossible de prouver la vérité (je veux dire juridique, des faits) mais la question à mes yeux n’était pas là. Il y avait comme des éléments qui m’empêchaient d’avancer et qui progressivement s’enracinaient dans mon projet, au point d’en devenir le noyau même. Comme une supercherie, un guet-apens qui serait la constitution et la re-constitution même de l’affaire. Et de mon film.

Can you tell us about the material you used to research, document, prepare the installation? Did you meet some of the protagonists? Use mostly information found in mainstream media?

La question des sources est sans doute l’une des plus importantes à mes yeux. Il y a eu en 2008, quelques mois avant l’arrestation des jeunes de Tarnac, la publication d’un essai de philosophie politique très engagé intitulé « L’insurrection qui vient » signé par un comité invisible. Les politiques ont pris peur face à ce livre et ont considéré que les auteurs étaient les jeunes « anarcho-autonomes » de Tarnac. Ils ont pointé des liens entre des passages du livre et les sabotages des lignes de TGV et ils ont tenté de qualifier les sabotages d’actes terroristes. Autrement dit, ce livre était une bombe et ses auteurs des terroristes.

Il y avait bien sûr les articles de presse sur l’affaire, dont nombreux publiés par Mediapart. Je lisais tout ce que je trouvais. Je me souviens en particulier d’un article d’Edwy Plenel (président de Mediapart) du 25 avril 2009 qui titrait « Pourquoi l’affaire de Tarnac nous concerne tous ». Il y expliquait de manière limpide (ce qui fut rare dans cette affaire) qu’il était question dans l’affaire de Tarnac de violation de principes démocratiques vitaux et combien cela nous concernait tous, même et surtout, si nous ne partagions pas les idées de ceux qu’elle mettait en cause. L’essentiel était dit. Quoi qu’ils aient pu penser ou écrire, et même quoi qu’ils aient pu faire, tant que leur culpabilité n’était pas démontrée, ils avaient droit à la présomption d’innocence. Etrangement, il n’était désormais plus question pour moi de chercher à savoir s’ils étaient coupables. Mais le problème, c’est qu’une fois que la présomption d’innocence est bafouée, c’est trop tard, les politiques ont gagné, parce que dans l’esprit des gens, ils sont coupables.

Ensuite, je suis entré en contact avec David Dufresne, ancien journaliste chez Mediapart qui avait couvert l’affaire de Tarnac. Au moment où je lui ai écrit, en novembre 2011, il achevait son livre « Tarnac, Magasin général ». Je lui ai écrit un long email afin de confronter ma vision tordue auprès de quelqu’un qui connaissait bien l’affaire. J’avais besoin de savoir si je ne me plantais pas complètement. Il faut dire qu’à l’époque tout était très confus. Et c’est probablement ce chaos qui m’avait attiré. J’y voyais quelque chose de totalement irréel.

J’ai donc lu le livre de Dufresne qui m’a beaucoup appris sur l’affaire mais surtout, dès le début de l’affaire fin 2008, j’avais lu les textes et essais du collectif Tiqqun, qu’on attribue généralement au Comité invisible, auteur de « L’insurrection qui vient ».

Je ne voulais pas interroger les protagonistes, ça me semblait aller totalement contre leur désir de discrétion. Je leur ai quand même écrit en leur disant que j’allais venir à Tarnac et que j’aurais aimé les rencontrer. Ils ont confirmé mon intuition en me disant qu’ils préféraient rester dans l’ombre. Quand j’étais là bas, j’ai croisé une des inculpées. On s’est dit qu’on se reverrait pour parler. Et puis il a beaucoup neigé, il faisait très froid, et je ne l’ai jamais revue.

Ça c’est pour mes sources. Je dois préciser que, bien qu’ayant à l’origine une formation de juriste, je suis devenu artiste. Contrairement à l’avocat ou au journaliste qui couvre une affaire, je peux exclusivement me nourrir des confusions, des incohérences, des manques, des failles et de mes intuitions. Plutôt que de me servir de ce qui apparaît, j’exploite ce qui n’apparaît pas. Puisque rien n’était clair dans l’affaire, j’ai décidé de produire mes propres archives. En cela, le film virtuel prend la forme d’un document comme un autre, bien que construit de toute pièce. C’est une manière de révéler la supercherie et, en même temps, je transmets l’essence de l’affaire : la reconstitution. Mon film et mon installation devenaient des sources secondaires. Ainsi tout en la révélant, je contribuais à la supercherie, je faisais exister le mythe.

Autre chose : j’ai écrit un scénario, tiré de « faits réels ». Je précise « faits réels » parce que l’impossibilité du récit commençait là. Les faits sont par nature réels mais, dans l’affaire de Tarnac, chaque élément semblait discutable. Le « réel » n’apparaissait jamais de manière évidente. Au point que mon projet documentaire était en quelque sorte déjà faussé, comme tué dans l’œuf. C’est donc là-dessus que je suis mis à travailler, sur cette impossibilité. Pas de preuve, pas de trace, rien. Excepté des livres. Et ça c’est fondamental, la source principale de l’Etat, qu’ils ont considéré comme un élément de « preuve », était un livre.

Now i’m also curious about the form that the installation takes. First, there’s a 3 screen installation showing images you shot on location. And in an adjacent room, video game images chart the whole affair in complete silence, with members of the Tarnac Nine wearing masks. Why did you chose to show explore the subject this way? Why are the protagonists silent? Why using both videos of the location and virtual images?

J’ai voulu fragmenter. Le dispositif double installe une sorte de miroir. Je voulais créer un hors champ, disjoindre les points de vue. Chaque film est le pendant de l’autre. D’un côté ce qui semble être le réel, de l’autre le virtuel. Quelle que soit la réalité que l’on décide de voir, elle reste amputée. C’est comme si aucune des deux vidéos ne suffisaient à raconter l’affaire mais que la seule chose qui pouvait en rendre compte ce serait le dispositif même, sa fragmentation, le partage entre différents matériaux, réel et virtuel.

Le processus de travail a été laborieux. Chaque étape, qui devait s’intégrer au projet, servait de base aux étapes suivantes. Je suis parti en tournage à Tarnac et à Dhuisy (le lieu des sabotages) avec mon chef op et mon monteur qui, à défaut d’argent pour payer un ingé son, avait accepté de prendre le son. L’idée était de faire un « film sans traces ». Je voulais montrer les lieux de cette affaire qui avait fait trembler la France. Bien sûr c’était des lieux déserts… Et sur ces images, il fallait qu’on entende les paroles des inculpés. J’ai pris des extraits des essais qu’on leur attribue ainsi que de l’entretien magnifique de Julien Coupat (principal suspect dans l’affaire de Tarnac) paru dans Le Monde du 26 mai 2009, alors qu’il était encore détenu dans la prison où il est resté six mois. Instaurer une voix off, c’était une manière de confronter le spectateur. Vu le chaos qui régnait, il fallait à un moment choisir de dire les choses. On peut toujours tourner autour du pot mais la seule chose qui me paraissait « vraie », c’était leur parole. Et il fallait qu’ils soient entendus. Si on reste et qu’on écoute ce qui est dit, on est forcément interpellé, c’est une « affaire de sensibilité » (dixit Julien Coupat).

La création du « jeu vidéo » a été la plus importante. Pendant cinq mois, j’ai travaillé dans Garry’s mod, un logiciel de jeu vidéo, avec deux animateurs 3D. A partir de mes rushes et d’images tirées de Google Earth, nous avons opéré une reconstitution de Tarnac et Dhuisy. Je voulais réaliser un film qu’on ne sache pas par quel bout saisir. Comme dans « Valse avec Bachir » de Ari Folman, j’avais l’impression qu’il fallait passer par l’animation pour dire le réel. L’idée était de mettre en place le suspect idéal mais que rien ne se passe. Aucune action. Aucun crime. Rien. Seule la mise en scène qui le suggère. Venir tordre l’univers du jeu vidéo, le détourner, s’approprier les bugs, les contraintes successives, les impossibilités de faire faire ce que l’on veut aux personnages, tout cela crée une forme d’étrangeté.

La particularité, c’est qu’il s’agit d’un véritable “tournage virtuel”. Je pose des caméras dans les décors reconstitués avec mes graphistes et je filme les personnages qu’on a modélisés. Je travaille donc plan par plan et non image par image. Ma démarche est donc, de ce point de vue, plus proche du cinéma que de l’animation.

L’idée du masque est née de l’anonymat des protagonistes de l’affaire. Cela faisait partie de leur idéologie : « être visible, c’est être à découvert » écrit le comité invisible dans « L’insurrection qui vient ». IIs n’acceptaient pas, ou très peu, d’interviews. Ils étaient très méfiants. Même en sortant de prison, Julien Coupat est sorti dans le coffre d’une voiture, évitant ainsi les rencontres avec les medias. Apparaître dans l’affaire, c’était rentrer dans le jeu du politique et dans la « société de spectacle ». Les masques, ça les rendait anonymes mais ça les rendait suspects aussi, et puis ça en faisait des acteurs de la Comedia del arte. Ils avaient fini au coeur du spectacle. Malgré eux, ils faisaient vivre le mythe. Et puis, c’était tout simplement une manière de jouer avec les codes du jeu vidéo. Les « bons et les méchants », tous masqués, ça ramenait la confusion générale au sein du film.

Je n’étais pas convaincu de leur innocence, mais ça n’avait plus aucune importance pour moi. En revanche, j’étais convaincu que le droit avait été violé. Le livre pouvait déplaire au pouvoir, ça n’en faisait pas des terroristes. Donc j’ai mis en scène l’étrange, la peur, la figure du coupable, avec une certaine ironie, pour que le spectateur s’interroge « mais sont-ils vraiment coupables ? qu’ont-ils fait au juste ? ».

Le silence des protagonistes, comme le masque d’ailleurs, joue sur l’ambigüité : il efface toute trace de culpabilité et en même temps accroît la suspicion. D’autre part, c’est assez proche de la « vérité » puisque les inculpés se sont très peu exprimés au sein même de l’affaire. C’est d’ailleurs ce qui a pu rendre les politiques fous. Et c’est sans doute ce qui les a « sauvés »… En revanche, la voix off du triptyque a été pensée en écho au film d’animation. Même sans visage, leur parole est donc présente. Leurs textes hantent le film.

While working on this interview, i’ve been reading about the Tarnac Affair and trying to figure out where the “Tarnac Nine” are nowadays, if they have been cleared of the accusations, etc. But i couldn’t find any satisfying answer. Information seems to stop in 2010. Has the State and the police formally apologized for the unjustified accusations? And what does the general public think? Do they still believe that the protagonists are guilty or is it now clear to everyone that there was little to no evidence to sustain the accusations?

Je ne connais pas la situation juridique actuelle des inculpés mais je sais que les jeunes de Tarnac ont été longtemps (encore lorsque je réalisais ce projet) interdits de quitter le territoire et sous contrôle judiciaire. Progressivement, on a pu voir quelques évolutions. En novembre 2011, suite à l’accusation par les jeunes de Tarnac de la police antiterroriste d’avoir rédigé un PV mensonger, le parquet de Nanterre a ouvert une information judiciaire pour « faux et usage de faux en écriture publique ». En mars 2012, le juge d’instruction antiterroriste Thierry Fragnoli s’est dessaisi de l’affaire. Et enfin, le 24 octobre 2012 (quatre ans après le début de l’affaire !), le journal Le Canard enchaîné a révélé que la carte bancaire de Yildune Lévy, compagne et depuis lors épouse de Julien Coupat, avait été utilisée à Paris dans la nuit du 7 au 8 novembre 2008, donc loin de Dhuisy, le lieu du sabotage. Un retrait bancaire fait état d’un retrait de 40 euros à Pigalle à 2h44. Deux jours après, la Cour d’appel de Versailles ordonnait l’audition de 18 policiers ayant participé à la surveillance des membres du groupe. Et, le 12 novembre 2012, Julien Coupat a pour la première fois brisé le silence et accepté de répondre aux questions des journalistes. « Désormais, la seule façon de disparaître, c’est d’apparaître” s’expliquait-il. Je n’ai pas connaissance que la justice ait déjà prononcé le non-lieu.

Concernant l’opinion générale, je pense qu’elle a dû évoluer au cours de l’affaire. Pendant les trois premières années, excepté sur Mediapart, il y avait très peu de contre-information. Je pense malheureusement que quand les medias suivent le politique et bafouent la présomption d’innocence, les citoyens suivent. (Libération, journal communément considéré à gauche, avait titré le 12 novembre 2008 : « L’ultra gauche déraille » pour ensuite revenir sur sa position mais c’était trop tard). Je pense que beaucoup ont du penser qu’ils étaient coupables. Surtout, comme je l’ai écrit plus haut, que les inculpés créaient le mystère, notamment par leur refus d’apparaître. Depuis la sortie du livre de David Dufresne « Tarnac, Magasin général », l’élection de François Hollande, ainsi que les derniers éléments judiciaires de l’affaire, la bavure semble avérée. Mais en réalité je pense que la plupart des gens ne se sentent pas concernés.

There’s this really interesting essay written in 2009 by Alberto Toscano for The Guardian. He argues the Tarnac Nine has demonstrated that we are losing “the political literacy, and the legal capacity, to distinguish between sabotage and terrorism, vandalism and mass murder, as every oppositional alternative to the status quo is swallowed up under the umbrella of terrorism. ”

Was your work commenting on this kind of issue? Or did you want spectators to draw their own conclusion?

Comme je l’ai dit plus haut, avant de me tourner vers l’art, j’ai fait des études de droit. Il est évident que la question de la qualification pénale de « terrorisme » m’a beaucoup préoccupé dans cette affaire. Souvenons-nous que les « terroristes » de 40 ont été considérés comme des héros à la Libération. Mais vous savez, tout est lié. Dans une affaire pareille, on ne peut pas prendre une partie et en délaisser une autre. Le reste, c’est une question de « comment transmettre ». Je pense que le spectateur ne comprend jamais aussi bien que quand il fait son propre trajet. Il faut qu’il soit libre de comprendre.

J’ai voulu mettre en évidence l’absurdité d’une affaire qui s’est bâtie sur la publication d’un livre. L’incrimination de la pensée est un cauchemar qui échappe à l’entendement. C’est de la pure littérature (ou, comme vous l’écrivez, c’est aujourd’hui digne de séries télévisées). On est dans Le procès de Kafka, dans 1984 de Georges Orwell, on est dans de la science fiction. Dans Minority Report, Philip K. Dick imagine une société où l’on traque le « Précrime », c’est-à-dire avant que le crime ne soit commis. Seule la fiction pouvait faire réfléchir. Et paradoxalement, les gens y voient un documentaire. Pourtant j’ai écrit un scénario à partir de faits totalement réinterprétés. Comment aurais-je pu faire autrement ? Qu’est-ce qui est réel finalement, à part les livres que j’ai lus et le montage d’une affaire dont on ne sait rien ? L’absence de traces ou comment créer une archive avec de la fiction, voilà l’enjeu. Peut-on voir dans des reconstitutions virtuelles, dans un jeu vidéo, un élément de preuve, une archive ?

Merci Joachim!

Crédits:

Film d’animation

scénario et réalisation : Joachim Olender ; production : Le Fresnoy et Solilok asbl ; animation 3D : Thomas Jorion et Alexis Fradier ; montage image : Yannick Leroy ; montage son : Yann-Elie Gorans ; mixage : Simon Apostolou ; étalonnage : Baptiste Evrard

Triptyque

scénario et réalisation : Joachim Olender ; production : Le Fresnoy et Solilok asbl ; voix off : Soufian El Boubsi ; musique : Pierre Hujoel ; image : Vincent Pinckaers ; son : Yannick Leroy ; montage image : Yannick Leroy ; Mmontage son : Yann-Elie Gorans ; mixage : Simon Apostolou ; étalonnage : Baptiste Evrard