Helen Pynor, Head Ache (detail), 2008

Helen Pynor, Head Ache (detail), 2008

Featuring over 150 artefacts including real brains, artworks, manuscripts, artefacts, videos and photography,Brains: The Mind as Matter follows the long quest to manipulate and decipher the most unique and mysterious of human organs, whose secrets continue to confound and inspire.

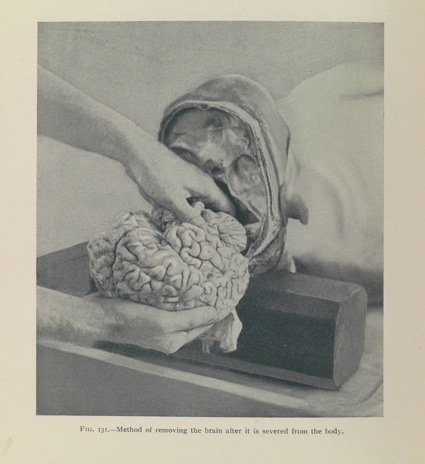

Examination of the skull and brain: method of removing the brain after it is severed from the body. Henry W. Cattell, 1903. Wellcome Library, London

Examination of the skull and brain: method of removing the brain after it is severed from the body. Henry W. Cattell, 1903. Wellcome Library, London

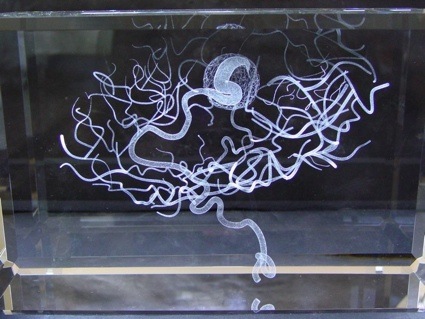

Katharine Dowson, Memory of a Brain Malformation, 2006

Katharine Dowson, Memory of a Brain Malformation, 2006

As the intro to the exhibition says, the works displayed include real brains. Complete brains, bits of brains, brains that have been freeze-dried, dessicated or galvanized. The slices of Albert Einstein’s brain seem to gather much attention from the press and visitors alike. I doubt the fascination would have filled its original owner with euphoria. He had indeed expressed the wish to be cremated intact.

The remains of the physicist are in awkward company. They are shown next to a phial of tissue allegedly coming from William Burke’s brain. With his accomplice William Hare, Burke made a living from murdering poor people and selling their bodies to Dr Knox’s anatomy school. He was hung on 28 January 1829. Ironically, Burke’s body was dissected, exhibited to the public in the Edinburgh University Museum and souvenirs were made and sold from his skin.

Other brains on show includes the one of suffragette Helen H Gardener, the left hemisphere of mathematician Charles Babbage’s brain, and the segment of a suicide victim, with a bullet lodged in it. This one came with a text explaining that bullet wasn’t “the fatal one”.

Installation view of ‘Brains: The mind as matter’. Courtesy: Wellcome Library, London

Installation view of ‘Brains: The mind as matter’. Courtesy: Wellcome Library, London

Unlike previous exhibitions such as Dirt: The filthy reality of everyday life,High Society: Mind-Altering Drugs in History and Culture or War and Medicine, Brains: The Mind as Matter has a seemingly very specific, very narrow focus: the brain. Not even the mind, just the physical organ. Yet, the exhibition branches out into issues of ethics, history, and reminds us that while some of the moments in the history of neuroscience are glorious, others are downright disgraceful. The exhibition displays a number of instruments designed to measure the brain. The one below was developed by Sir Francis Galton, the ‘father of eugenics‘. Using a variety of ‘anthropometric’ devices, Galton sought evidence of links between physical appearance and the supposed evolutionary progress of different population groups.

Headspanner, c.1896. The Galton Collection, University College London

Headspanner, c.1896. The Galton Collection, University College London

This kind of discourse was particularly well received during the Nazi period. A series of photos and letters document the case of 3 brothers, Alfred, Gunther and Herbert K. aged 3, 7 years old and 15 months. They suffered from a rare hereditary neural disease and were likely murdered in 1942 and 1944. Their mother was told that they had died of pneumonia. Like many other people suffering from neural disease, they have probably been gassed or drugged, their brains harvested and examined by neuropathologists who went on to continue eminent careers long after the war. As for the specimens taken from the victims, they were used by researchers until recent decades.

Daniel Alexander, Children’s cemetery: the grave of Alfred, Günther and Herbert K (2003)

Daniel Alexander, Children’s cemetery: the grave of Alfred, Günther and Herbert K (2003)

The quest to understand the functioning of the brain is as grandiose and challenging as the one to send men in outer space. Brains: The Mind as Matter can keep you in the rooms of the Wellcome Collection for hours on end. It’s an absorbing, educational and at times disturbing exhibition.

I was particularly fascinated by the photos amassed by American neurosurgeon Harvey Williams Cushing. Taking pre- and post-operative photographs were part of his practice. Two examples below:

Pre-operative photograph of female patient with craniopharyngioma, 1919. Cushing/Whitney Medical Library, Yale University

Pre-operative photograph of female patient with craniopharyngioma, 1919. Cushing/Whitney Medical Library, Yale University

Many of the patients in these photographs presented with much more advanced tumours than would normally go unchecked today. The 15-year-old subject of this photograph suffered years of headaches, nausea, convulsions, restricted development and impaired vision before being referred to American neurosurgeon and pioneer of brain surgery Dr Harvey Cushing. She was in and out of hospital for the next 12 years, although the final letter in her file, from her father in 1931, strikes an optimistic note and thanks Cushing for his care.

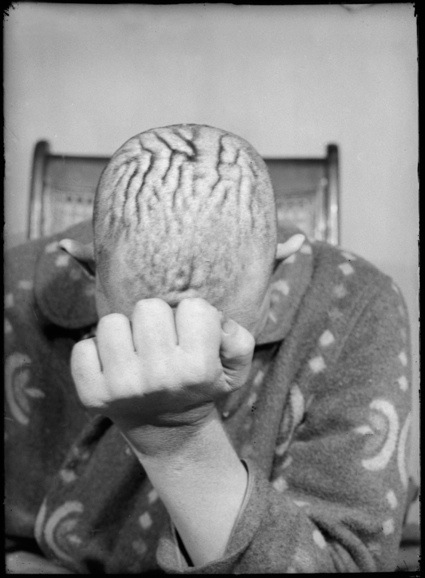

Pre-operative photograph of male patient with pituitary adenoma, 1914. Cushing/Whitney Medical Library, Yale University

Pre-operative photograph of male patient with pituitary adenoma, 1914. Cushing/Whitney Medical Library, Yale University

An excess of growth hormone caused by a tumour of the pituitary gland in the brain can result in acromegaly and gigantism, where the person grows very tall and suffers a coarsening of the facial features, enlarged hands and feet, and thickening and wrinkling of the scalp. Unfortunately, this patient died after his second operation; his skeleton was preserved and photographed in comparison with a normal specimen.

More images from the show:

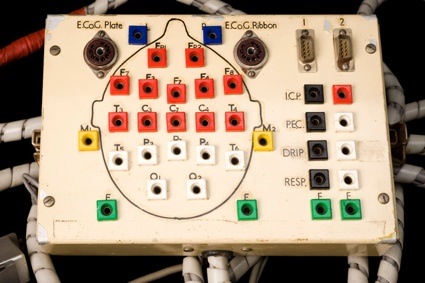

Electrode head board, Bristol, England, 1958. Courtesy: Science Museum

Electrode head board, Bristol, England, 1958. Courtesy: Science Museum

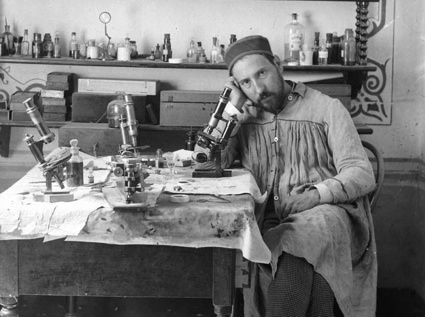

Santiago Ramón y Cajal

Santiago Ramón y Cajal

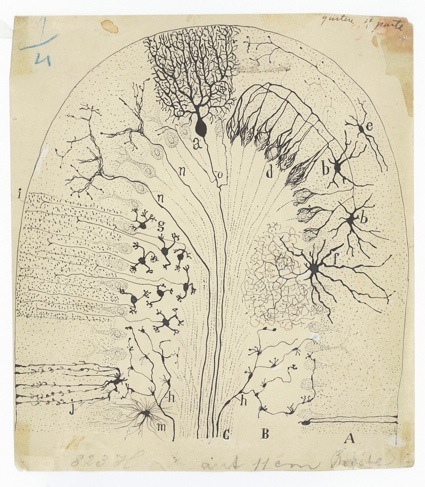

Santiago Ramón y Cajal, Parasagittal section of the cerebellum, 1894. Image courtesy of Cajal Legacy, Instituto Cajal (CSIC), Madrid

Santiago Ramón y Cajal, Parasagittal section of the cerebellum, 1894. Image courtesy of Cajal Legacy, Instituto Cajal (CSIC), Madrid

Spanish Nobel Prize-winner Santiago Ramón y Cajal, whose pioneering research at the turn of the 20th century gave us an understanding of the microscopic structure of the brain. Cajal had aspired to be an artist, but his father had insisted he follow the family tradition into medicine. He nevertheless made hundreds of drawing to illustrate brain structure.

Corrosion cast of blood vessels in the brain, 1980s. Gordon Museum, King’s College London

Corrosion cast of blood vessels in the brain, 1980s. Gordon Museum, King’s College London

Daniel Alexander, ‘Haus 40, interior’, Brandenburg State Hospital, 2011

Daniel Alexander, ‘Haus 40, interior’, Brandenburg State Hospital, 2011

Installation view of ‘Brains: The mind as matter’. Courtesy: Wellcome Library, London

Installation view of ‘Brains: The mind as matter’. Courtesy: Wellcome Library, London

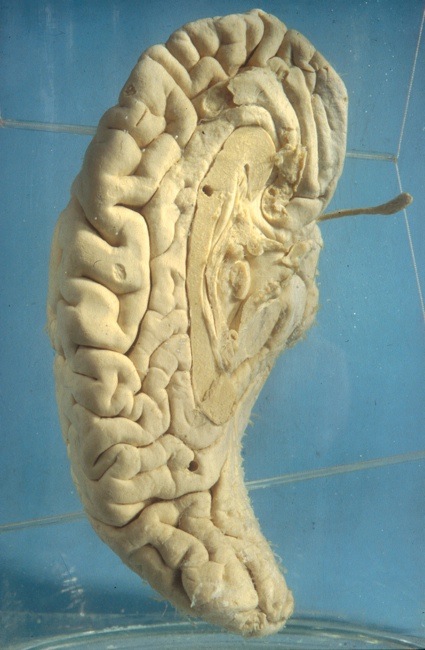

Left hemisphere of the brain of Charles Babbage. Wet specimen (human tissue), 1871. Hunterian Museum, Royal College of Surgeons, London

Left hemisphere of the brain of Charles Babbage. Wet specimen (human tissue), 1871. Hunterian Museum, Royal College of Surgeons, London

English mathematician Charles Babbage donated his brain to be analyzed. He is regarded as a “father of the computer”, having invented in 1822 the ‘Difference Engine’, a mechanical computer complete with printer. One of his assistants was Augusta Ada King, the Countess of Lovelace.

Trephination set. Sirhenry, Paris, 1771-1830. Science Museum, London

Trephination set. Sirhenry, Paris, 1771-1830. Science Museum, London

Trephines are the surgical devices used for trephination, or trepanning. The basic practices and tools have remained largely unchanged for centuries. Among the trephines themselves, with their cylindrical blades, are a large brace to hold the trephines during drilling, two rugines to remove connective tissue from bones, two lenticulars to depress brain material during surgery and a brush to remove fine fragments of bone.

Installation view of ‘Brains: The mind as matter’. Courtesy: Wellcome Library, London

Installation view of ‘Brains: The mind as matter’. Courtesy: Wellcome Library, London

Brains: The Mind as Matter remains on show at Wellcome Collection in London until 17 June.

Previously at the Wellcome Collection: Mind Over Matter, Dirt: The filthy reality of everyday life, Art, bricks, domestic dust, High Society: Mind-Altering Drugs in History and Culture, Exquisite Bodies at the Wellcome Collection, War and Medicine exhibition at the Wellcome Collection in London.