Z33 House of Contemporary Art in Hasselt, Belgium, has just opened an exhibition with a very promising title. Architecture of Fear explores how feelings of fear pervade daily life in the contemporary media society.

Z33 House of Contemporary Art in Hasselt, Belgium, has just opened an exhibition with a very promising title. Architecture of Fear explores how feelings of fear pervade daily life in the contemporary media society.

I’m going to visit it on Thursday but in the meantime i thought i’d ask one of the participating artists, Jill Magid, to tell us about the work she is showing at Z33 and more generally about her experience with impersonal power structures (police, intelligence agencies, security systems, etc.) which, whether they contribute to it or fight it, are part of this ‘architecture of fear.’

One of Magid’s most ironic works is System Azure. In 2003, the artist introduced herself to the Amsterdam Police as a “Security Ornamentation Professional” working for a fictitious company. Magid’s proposal to embellish police cameras was accepted and she was hired to hand-glued rhinestones to security cameras at the Amsterdam Headquarters of Police, a work that had previously been rejected when she had first presented it as an art project.

Evidence Locker, 2004

Evidence Locker, 2004

In Evidence Locker, Magid developed a personal relationship with the operators of Liverpool’s citywide video surveillance cameras. Dressed in red, she had them follow her every steps as she moved across the city. Back in New York, she managed to gain the trust of a police officer and infiltrate his professional (and personal) world. Magid pushed even further her enquiries into the personality of the human beings hidden behind the faceless instruments of power and surveillance in 2005, when she met with employees of the Dutch secret service, the AIVD, and almost turned into an agent herself for a commission by the AIVD itself to create an artwork that would help them improve upon their public persona and provide them ‘with a human face’.

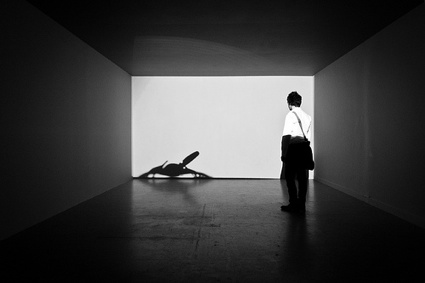

A Reasonable Man in a Box, 2011. View of the installation during the opening Architecture of Fear. Photo: Kristof Vrancken / Z33

A Reasonable Man in a Box, 2011. View of the installation during the opening Architecture of Fear. Photo: Kristof Vrancken / Z33

The work Magid is showing at Z33 this Fall, A Reasonable Man in a Box, was inspired by the “Bybee Memo”, a 2002 document signed by Assistant Attorney General Jay Bybee. The document considered the use of mental and physical torment and stated that acts widely regarded as torture might be legally permissible under an expansive interpretation of Presidential authority during the “War on Terror.” The memos were declassified by President Obama in 2009. One of the acceptable methods of “enhanced interrogation” described in the document involved the use of a confinement box. The prisoner would be confined inside this box with insects which would not harm them. The people in charge would know that the insect or the animal is innocuous but would leave the prisoner in the dark about it.

Magid’s take on the interrogation technique is a room where the silhouette of a big hissing scorpion is projected wall. Every once and a while a pair of tweezers appears on screen to catch the animal by the tail.

Hi Jill! I”ve been following and admiring your work ever since i started blogging. So far i associated you with performative works in which you put yourself on the front line (Lincoln Ocean Victor Eddy, Lobby 7 or Evidence Locker for example.) There’s no visible trace of you in “A Reasonable Man in a Box”. How do you decide whether you are going to be so visibly involved and present in a new work or when you are going to step back?

The Spy Project— in which I am the main protagonist, finished just before I began the research that led to A Reasonable Man in a Box. The Spy Project involved the censorship of my novel by the Dutch secret service about my experience working with it. This redacted manuscript got me to thinking about other government-censored documents. Simultaneously I was researching torture as it is used by democracies, and how these practices are hidden from public view or scrutiny. Both paths led me to the Bybee Memo. As the document was already complete and therefore no longer open to change, I did not feel I could not enter into it as a protagonist. I found a different way to engage it.

A Reasonable Man in a Box. Installed at the Whitney Museum of American Art, 2010 (entrance)

A Reasonable Man in a Box. Installed at the Whitney Museum of American Art, 2010 (entrance)

A Reasonable Man in a Box. Installed at the Whitney Museum of American Art, 2010

A Reasonable Man in a Box. Installed at the Whitney Museum of American Art, 2010

I saw images and read descriptions of the installation at the Whitney Museum. The room where the film was screened seemed to be spacious, with a visible entrance/exit. From what i gathered it still made quite an impact on visitors. But why didn’t you chose to take a more extreme road and show the video in a claustrophobic space or in one that looked more like a cell or in a room you couldn’t exit until the end of the video?

Would it have been too literal?

Will the setting of the work at Z33 be similar to the one at the Whitney?

I was not trying to make the viewer the tortured victim inside the box (i.e. gallery); rather, I wanted the viewer to consider the fundamental questions at the heart of the memo: what is reasonable; and what is a reasonable man in a box? The install is creepy, uncomfortable, and simple. The gallery becomes a shadow box: the shadow of the scorpion in the gallery is proportional to ‘the stinging insect’ in a confinement box. The shadow, as projected in both the Whitney and at Z33, is larger than life, as the rooms in which they are installed are of course bigger than a confinement box, which is only the size of a person sitting or standing. The fragment of the Bybee Memo discussing the enhanced interrogation practice of placing a man in a box with a stinging insect is also enlarged to scale. This enlargement is a kind of highlighting. Through it, the language has been made physical, enterable. Under these conditions, the memo and the questions it provokes can be examined and experienced on a personal level.

The installation was inspired by the “Bybee Memo”. I had never heard of it before. In Europe we are familiar with stories about the kind of music played to drive prisoners crazy, rendition flights (which couldn’t have been carried out without the complicity of European governments anyway), etc. But i think that the “Bybee Memo” is less well-know here. Is that the same in the USA? Did the installation play with something that the audience was familiar with or did it reveal the existence of that “Bybee Memo” as well?

There seem to be varying degrees of awareness about The Torture Memos (the common name for the Bybee memos), and the CIA’s Enhanced Interrogation program. (Most notably in the press was the detailed practice of waterboarding, a type of enhanced interrogation practiced that simulates drowning.) Regardless, I felt 1. That it was an important document to (re)consider, and 2. That the installation was self-contained and therefore, did not rest upon a prior knowledge.

The practice of placing a man in a confinement box with an insect was detailed in the Bybee Memo that was released in 2009 when President Obama came to office. I’d heard of the memo before working on this project, but I’d never actually read it (It’s 18 pages of legalese). I have not yet met more than a few people who have. When I in fact did read it, I was shocked– more by its language and (absurdist) ’empirical’ logic than even by the practices it invoked and legalized.

I’m interested in things that appear to be obvious or known, but aren’t. I wanted to slow down the memo, focus and enlarge it, so that I could really look at it. The Bybee memo successfully changed the definition of torture in the United States for half a year, making acts that under the Geneva Convention were considered torture, legal.

A Reasonable Man is one of a series of projects that deal with secret services. In previous works you explored the Dutch secret service and engaged with a number of intimate relationships with members of the AIVD. The purpose of these meetings was “to collect personal data of the agents and to use this information to find the organization’s face.” So how were these people like? Is secret service all James Bond, exciting adventures and fearless clean-shaved men?

What I find most intriguing about my engagements with government institutions is that in entering them I find that they are far more fantastic than I could have imagined, and rarely resemble what I have seen in films. I never cease to be surprised as to what I find and what I cannot find, and how both of these things affect me. The people I have engaged with are as varied and complex inside the service as they are outside of it.

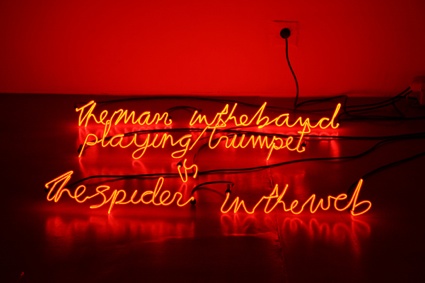

I Can Burn Your Face, part of the Spy Project

I Can Burn Your Face, part of the Spy Project

While working on A Reasonable Man, how much information did you manage to find about the “enhanced interrogation” of high-level Al Qaeda operatives? Did you contact anyone? Meet? Found other pieces of information? How close did you manage to get to the issue?

I focused on the memo and understanding it. I was also interested in the memo as to what was visible and what was missing due to redaction, and how my understanding of the former was influenced by the latter. The idea of the shadow– of not being able to see the real but only its ghost, had much to do with this schism of visible/hidden.

When I had questions about the memo, I did have some people to turn to. I was in contact with an investigative reporter (who has both a military and intelligence background) that had been embedded with the US army in both Iraq and Afghanistan and had visited Abu Ghraib (He is a protagonist in my current project), and a PhD student at NYU studying torture, law and the media. I also read about torture and democracy in books and in the news. These contacts and this research helped me approach and re-approach the memo with a continually deeper understanding.

Are secret services a theme you’re going to keep on exploring?

I never know where the work is going from project to project, as my process is organic. That being said, secret services will no doubt continue to interest me. They epitomize many of my interests (secrecy, intimacy, power, legal and coded language), and they are inexhaustible. I still find myself drawn to any story on intelligence matters in the paper. I’m still a little hurt the CIA has never contacted me; )

System Azure | Rhinestoning Headquarters

System Azure | Rhinestoning Headquarters

I’m curious about something else… What happened to the rhinestone-studded surveillance cameras you installed in Amsterdam?

They are still there, in full glamour (perhaps with a little city dirt and grime) on the headquarters of the police in Amsterdam. Check them out. They’re permanent.

Thanks Jill!

Architecture of Fear remains open at Z33 in Hasselt, Belgium through December 31, 2011.