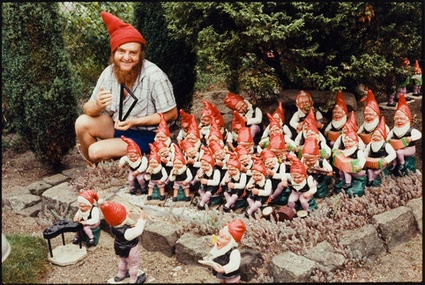

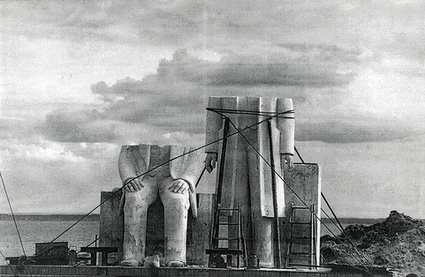

Sibylle Bergemann, from the series Das Denkmal (A Monument), 1975-1986,

Sibylle Bergemann, from the series Das Denkmal (A Monument), 1975-1986,

After Postopolis, a talk at ENSAD in Paris, a few days at the STRP festival in Eindhoven, a couple of days washing dirty clothes, queuing all over the city and catching up with work at home, i’m back on the road again and will probably disappear for half a week unless i manage to extract myself from the ‘evening entertainment’ that -rumour has it- will be forced upon me these coming days.

Gundula Schulze, Ohne Titel, Dresden (1986)

Gundula Schulze, Ohne Titel, Dresden (1986)

The plan was to write a long and well-documented post about a remarkable exhibition i saw at LACMA in Los Angeles a couple of weeks ago: Art of Two Germanys/Cold War Cultures, i promised myself i’d do it before i get on the plane to Linz but guess what? The plan failed miserably. So here, dear reader, for your eyes only comes a sloppy version of what this post should have been. It is not exhaustive, it is not very informative but it might give you an idea of a couple of works i found particularly striking. Sometimes i might even explain why:

Gunther Uecker’s “TV auf Tisch (TV on Table)”, 1963

Gunther Uecker’s “TV auf Tisch (TV on Table)”, 1963

Art of Two Germanys/Cold War Cultures: For East and West Germany during the Cold War, the creation of art and its reception and theorization were closely linked to their respective political systems: the Western liberal democracy of the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG) and the Eastern communist dictatorship of the German Democratic Republic (GDR). Reacting against the legacy of Nazism, both Germanys revived pre-World War II national artistic traditions. Yet they developed distinctive versions of modern and postmodern art–at times in accord with their political cultures, at other times in opposition to them. By tracing the political, cultural, and theoretical discourses during the Cold War in the East and West German art worlds, Art of Two Germanys reveals the complex and richly varied roles that conventional art, new media, new art forms, popular culture, and contemporary art exhibitions played in the establishment of their art in the postwar era.

Wolf Vostell, Coca-Cola

Wolf Vostell, Coca-Cola

I knew i would get a powerful lesson of history but i was not expecting the show to be so overwhelmingly good.

Installation view. Image courtesy LACMA

Installation view. Image courtesy LACMA

Artworks are choreographed in chronological order. First comes WWII’s immediate aftermath, 1945-1949, a dark period that would not be brightened by the division of the country into two separate states–East Germany and West Germany–along the lines of Allied occupation.

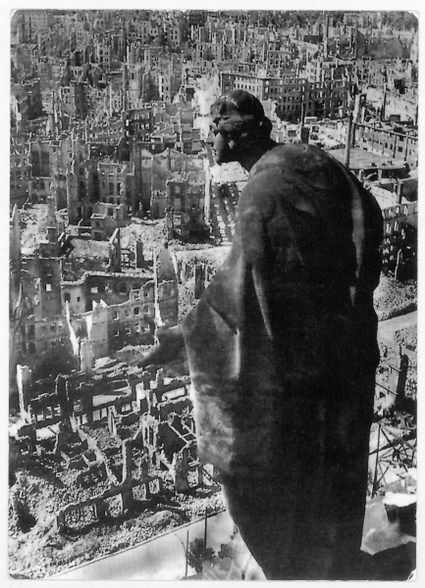

Richard Peter Sr.‘s B&W photographs that document the bombing of Dresden translate the mood better than any word could:

Richard Peter Sr., Dresden, from the series Dresden, eine Kamera klagt an (“Dresden, a photographic accusation”)

Richard Peter Sr., Dresden, from the series Dresden, eine Kamera klagt an (“Dresden, a photographic accusation”)

The second section, covering the 1950s, reveals the influence of Soviet and communist imagery on East Germany.

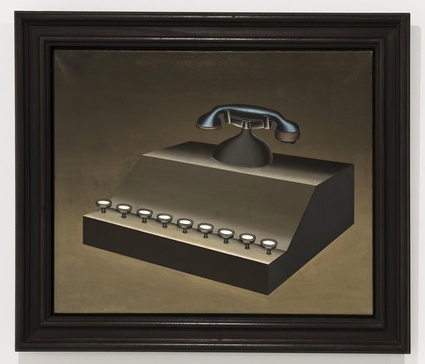

Konrad Klapheck, Erwartung, 1959

Konrad Klapheck, Erwartung, 1959

I particularly liked Konrad Klapheck‘s strict and flat paintings of various instruments and devices that have often been interpreted as a reflection of the stern and strong Nazi regime.

Heinz Mack, Relief Wand (Relief Wall), c. 1960

Heinz Mack, Relief Wand (Relief Wall), c. 1960

The Zero Group explored the relationship between science, technology and art. Strangely (to me) the movement was illustrated by an installation of it founder, Heinz Mack, that covered a wall with slowly spinning silver panels and disks.

Section three, dedicated to the 1960s and ’70s brings familiar faces: Joseph Beuys (right from my arrival at the exhibition, i was pacing the rooms wondering “so which Beuys will be here? Which one?), Sigmar Polke and Gerhard Richter.

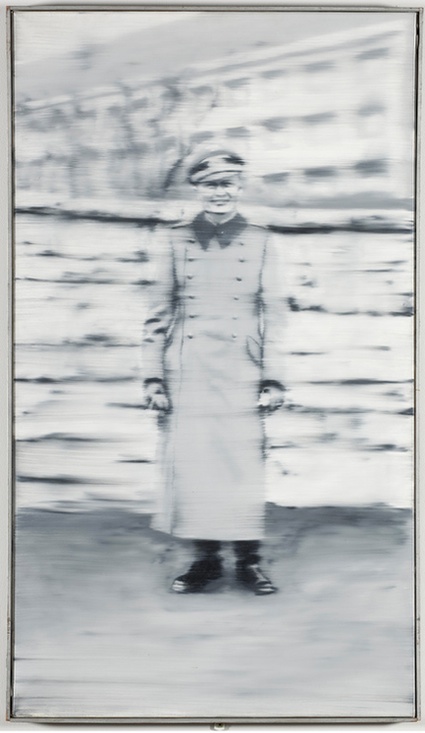

Gerhard Richter, Onkel Rudi (Uncle Rudi), 1965

Gerhard Richter, Onkel Rudi (Uncle Rudi), 1965

Uncle Rudi is a 1965 painting of a family snapshot of a SS officer, he was Richter’s uncle, “the Nazi in the family”. A smiling and proud young man who, years after the picture had been taken, evokes war and violence.

Raffael Rheinsberg, Hand and Foot, 1980. Installation shot

Raffael Rheinsberg, Hand and Foot, 1980. Installation shot

The final section brings us to the fall of the Berlin Wall. The most arresting piece in the section refers to the country’s darkest hours again. For the installation “Hand and Foot” (1980), Raffael Rheinsberg carefully ordered on the floor 400 shoes and gloves painted dark brown. The shoes belonged to forced laborers during World War II, they were found in an abandoned train station in Berlin.

Sibylle Bergemann, Ohne Titel (Gummlin) (Untitled [Gummlin] (1984)

Sibylle Bergemann, Ohne Titel (Gummlin) (Untitled [Gummlin] (1984)

Sibylle Bergemann’s photos of sculptures of Marx and Lenin have become symbols of the dismantling of the Soviet power in Eastern Germany, when in fact the images documented the monument’s birth, not its destruction.

Candida Höfer, Ratingen, 1976. From the series Turks in Germany, 1973-79

Candida Höfer, Ratingen, 1976. From the series Turks in Germany, 1973-79

Art of Two Germanys/Cold War Cultures is on view until April 19, 2009 at LACMA: Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

All images courtesy LACMA.