I first came across the name of this extraordinary place in one of the BBC’s Imagine-documentaries about German director Werner Herzog, who asked to be met in what he called one of his favorite places in Los Angeles, The Museum of Jurassic Technology. After locating it in Culver City, BBC’s Alan Yentob remarks: “I begin to understand why Herzog likes it here. The exhibits in the museum cross the line between fact and fiction, between reality and imagination.”

Front of the museum in Culver City, Los Angeles

Front of the museum in Culver City, Los Angeles

The collections of the museum, which was founded in 1989 and is being curated by David Hildebrand Wilson and Diana Wilson, span over three little buildings and consist of pieces from about a dozen sub-collections which are often centered around a certain subject such as belief and knowledge or personalities like Athanasius Kircher and their work. But, unlike what one might expect of a technology museum, throughout all of the exhibits, the boundaries between history and fiction, magic and reason, narrative and scientific method are in fact completely fluid (and the curators pleasurably make no effort to make things more clear, even indulge in elaborate descriptions and allusions that make it even more mysterious).

Many of the pieces consist of wonderfully crafted models and often amazing analog visual tricks for superimposing images. As a result, the whole space turns into a magical wunderkammer like I’ve rarely seen it, and probably one of the most astonishing approaches to the culture of art and technology on the planet. A few examples from the collections:

Duck’s Breath

Duck’s Breath

Tell the Bees…Belief, Knowledge and Hypersymbolic Cognition, is one of the newest additions and reflects on the relationship between ancient beliefs and recipes and how some of them still bear importance today. Yet, the application of lithium for neurological illnesses sits right next to the practice of letting children breathe in the cold breath of a duck or goose.

An especially intriguing practice refers to bees, which were understood to be related to and a manifestation of the muse from which comes the bees alter identity of the muse’s bird. And, the practice of telling of the bees of important events in the lives of the family has been for hundreds of years a widely observed practice and, although it varies somewhat among peoples, it is invariably a most elaborate ceremonial. The procedure is that as soon as a member of the family has breathed his or her last a younger member of the household, often a child, is told to visit the hives. and rattling a chain of small keys taps on the hive and whispers three times: “Little Brownies, little brownies, your mistress is dead.”

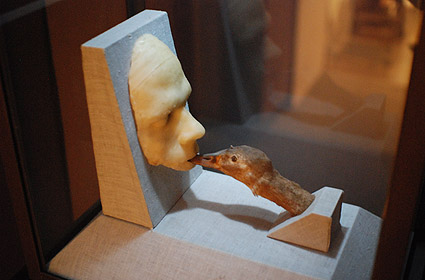

The Conversion of St. Eustace at Mentorella

The Conversion of St. Eustace at Mentorella

Another collection, titled The World is Bound with Secret Knots, is devoted to the life and work of 17th century Jesuit scholar Athanasius Kircher, who dedicated himself to his parallel obsessions with magnetism, musicology, astronomy, archaeology, and linguistics, Kircher researched and compiled enormous amounts of data, invented innumerable optical, magnetic, and acoustic devices, composed music, poetry, and imaginative fiction. Created with the Karl Ernst Osthaus-Museum in Hagen, Germany, the exhibit consist of many gorgeous pepper’s ghost-style dioramas which illustrate Kircher’s range of fascinations and inventions, especially in relation to his theory of magnetism being the invisible force that binds all the universe together.

Garden of Eden on Wheels

Garden of Eden on Wheels

One part of the permanent exhibition focusses on Geoffrey Sonnabend, who in his three volume work Obliscence, Theories of Forgetting and the Problem of Matter, departed from all previous memory research with the premise that memory is an illusion. Forgetting, he believed, not remembering is the inevitable outcome of all experience. Sonnabend believed that long term or “distant” memory was illusion, but similarly he questioned short term or “immediate” memory. On a number of occasions Sonnabend wrote that there is only experience and its decay, by which he meant to suggest that what we typically call short term memory is, in fact, our experiencing the decay of an experience.

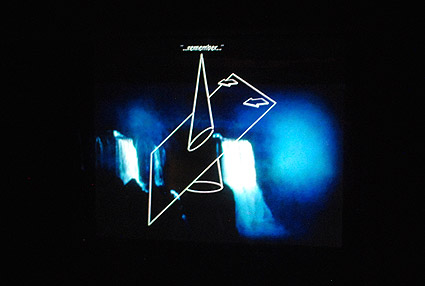

The Sonnabend Model of Obliscience

The Sonnabend Model of Obliscience

Sonnabend believed that this phenomenon of true memory was our only connection to the past, if only the immediate past, and, as a result, he became obsessed with understanding the mechanisms of true memory by which experience decays. In an effort to illustrate his understanding of this process, Sonnabend, over the next several years, constructed an elaborate Model of Obliscence (or model of forgetting) which, in its simplest form, can be seen as the intersection of a plane and cone.

As with many pieces in this exhibition, it’s practically impossible to find out whether Geoffrey Sonnabend even ever existed, but then again that’s part of it all. As Herzog puts it: “Inventions [in every sense of the word] have a deeper reach, a deeper stratum of truth quite often than we’d like to admit. And that’s the beauty of the museum here.”