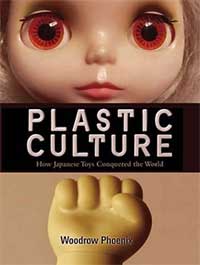

Plastic Culture – How Japanese Toys Conquered the World (Amazon USA

Plastic Culture – How Japanese Toys Conquered the World (Amazon USA

Editors say: Plastic Culture explores the world of toys: why we love them, what they represent, and why there is a growing market for “designer” and “art” toys aimed at adults. In this book, British author Woodrow Phoenix. takes a look at our relationship to toys in the twenty-first century, with particular reference to Japan–an exporter of both merchandise and ideas. Plastic toys based on Japanese comics, movies, and TV shows, from Astro Boy, Godzilla, and Gatchaman, to Power Rangers, Sailor Moon, and Pokémon have had a powerful effect on the imaginations and markets of the West, and have kick-started trends in design and pop culture that have crossed from Japan to the West and back East again.

I bought the book on an afternoon when i was in need of easy and shallow reading. But it proved to be much better than i expected.

The author argues that the current fascination for designers toys/urban vinyl is not about regression or infnatilism. It’s a mix of a “journey from wishspace to reality”, an object that triggers memories and as such it becomes a part of its owner, cultural objects shaped by the values and obsessions of the society that produced them and have recently become art pieces of a new genre. Designers vinyls are now sold in limited editions, snapped up by collectors and are exhibited in art galleries.

Ultraman toys from the ’70s and Garon vintage tin wind-up by Osaka Tin Toy

Ultraman toys from the ’70s and Garon vintage tin wind-up by Osaka Tin Toy

The book takes a look at the history of plastic toys, starting with the post-WWII period and the first plastic dolls manufactured by Ideal Novelty and Toy Company. Along with generic toys (trains, farm sets, teddy bears, etc) the biggest sellers were dolls modelled on film stars, comic book characters and later on science-fiction (robots, flying saucers, ray guns, etc.) then tv programs.

Later on came character merchandising and mascots created to attract customers and entice them to buy more of a given product. The best example of the phenomenon being breakfast cereals packets of the ’50s and ’60s. McDonald’s has understood the potential of giving away free toys with their Happy Meal menus. They started as early as 1977 and the success of the scheme has turned the fast food giant into one of the largest distributors of toys in the world.

The role of TV and character merchandising in disseminating culture was very important in Japan as well but the phenomenon of plastic toys took a more exciting turn in the ’80s, the decade when the word otaku started to get used in the country. Phoenix examined (a bit superficially imho) the social background of otaku and the emergence of “garage kits.” In the beginning of the ’80s young enthusiasts started making reproductions of characters from old animes, manga and special-effect movies first for their own use then they opened a studio at Kaiyodo. In 1999 though Kayiodo broke through the otaku barrier when they collaborated with confectionary company Furuta to produce the Choco Egg, each of the chocolate egg contains a limited-edition miniature model of an animal. The success was so big that Choco Egg speciality stores opened and fans started to trade duplicate or rare models.

After the long introduction on the history of toy culture for adults, the author proceeds by spotlighting several of the most famous designers of urban vinyl: starting with Michael Lau and Eric So who customized standard GI Joe action figures and turned them into either “gardeners” or Bruce Lee figures. Bounty Hunter, Presspop Gallery, Junko Mizuno, etc.

My sweet dog pull toy by Yoshitomo Nara and Murakami plushes

My sweet dog pull toy by Yoshitomo Nara and Murakami plushes

The most fascinating chapter for me was “The Toy as Art”. Takashi Murakami‘s view in particular. He believes that his plushes and figurines work both as fine art and toys, adding that the consumer groups for these will be different, “but it is the same aesthetic form in the end. And i would like it if these consumer groups were one and the same.” A confusion further increased by the fact that some of his sculptures actually had their toy form first, not the other way around. Toys are just another way to bring art in the life of everyone: “Art does not habe to be in a gallery. It does not have to cost thousands of dollars. It does not have to be elitist. It can be entertaining, and available.”

I was also glad to read the history of the Blythe doll. I discovered them a few years ago on a postcard. The doll had huge green eyes, jet-black hair and porcelaine skin just like my friend Caroline whom i miss a lot since she fell in love with a surfer and moved to Biarritz. The doll was launched in the US in 1972. Her eyes change color by pulling a cord at the back of her head. Children found her too scary and production stopped. In 1997, Gina Garan started using a 1972 Blythe to practice her photographic skills. She took the doll everywhere with her and took hundreds of photos. In 2002, Gina published her first book of Blythe photography, This is Blythe. Later that year, Hasbro gave the rights to make Blythe dolls to Takara of Japan. Blythe was used in a tv commercials in Japan, its re-vamped version was marketed to adults and became an instant hit. Success in Japan led Blythe back to the U.S.

I was also glad to read the history of the Blythe doll. I discovered them a few years ago on a postcard. The doll had huge green eyes, jet-black hair and porcelaine skin just like my friend Caroline whom i miss a lot since she fell in love with a surfer and moved to Biarritz. The doll was launched in the US in 1972. Her eyes change color by pulling a cord at the back of her head. Children found her too scary and production stopped. In 1997, Gina Garan started using a 1972 Blythe to practice her photographic skills. She took the doll everywhere with her and took hundreds of photos. In 2002, Gina published her first book of Blythe photography, This is Blythe. Later that year, Hasbro gave the rights to make Blythe dolls to Takara of Japan. Blythe was used in a tv commercials in Japan, its re-vamped version was marketed to adults and became an instant hit. Success in Japan led Blythe back to the U.S.

This month there was an exhibition of Blythe dolls dressed by designers at the Galeries Lafayette in Berlin)

More toys: Girltron that mix doll parts and transformer-style toys to create a new species; Tickle Me Elmo vibrating coat; Modified Toy Orchestra makes electronic music that derives from the modification of toys; and the magnificent Ken Stelarc.