Heba Y. Amin, Operation Sunken Sea: Relocating the Mediterranean, Inaugural Speech (video still), 2018

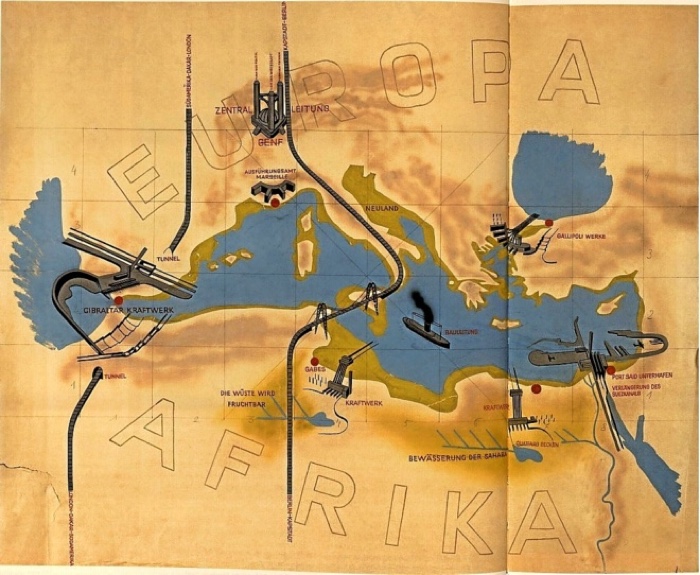

In the 1920s, German architect Herman Sörgel was working on Atlantropa (aka Panropa), a massive engineering and colonisation proposal that called for dams to be built across the Strait of Gibraltar, the Dardanelles, and between Sicily and Tunisia. The scheme would lower the Mediterranean Sea level. This drop would provide the government, company or alliance financing the colossal project two advantages. First, the difference between the Mediterranean and the Atlantic sea levels could be harnessed to generate hydroelectric power. An independent overseeing authority would then be able to cut the energy supply to any country posing a threat to peace. The other consequence of the sea level drop was it would partially drain the Mediterranean, providing land to settle and grow food as well as overland access to Africa. The engineer also planned to dam the Congo river to irrigate the Sahara and give shipping access to the African interior.

Atlantropa, Exhibition poster, 1932, via El Pais

Sörgel believed that uniting Europe and Africa as one continent would make that region of the world more powerful and peaceful. It would provide work and stimulate the post-WW1 economy. His techno-utopia is typical of a mindset that emerged in the early twentieth century and has never really left us: the technofix, this belief that technology can solve the world’s problems.

The engineer never took into consideration how other countries would react. How state borders would shift and how geographical changes might provoke new local conflicts over territory or resources. He didn’t think about the wildlife and human population that would be displaced. He completely ignored local cultures that would be erased and fishing communities that would lose their livelihood. The planned dams and bridges would landlock regions and cultures that had relied on the sea for centuries.

A look at current scientific knowledge also suggests that the implementation of the project would have had unpredictable and disastrous environmental consequences on a global scale. Once dry, the lands would have been too salty for most crops. The Mediterranean itself would have become gigantic hypersaline lakes. Even the cycles of rain would have been disrupted throughout the basin.

Claiming ownership over the Mediterranean Sea is not just utopian, it also demonstrates a deep-seated sense of entitlement…

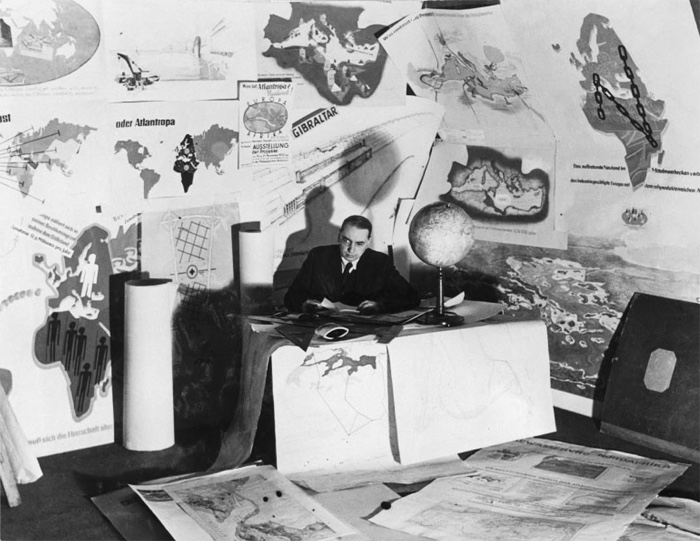

Herman Sörgel in the office of the New York Times, n.d. ADM 92. Photo Deutsches Museum

Heba Y. Amin, The Master’s Tools I (restaging of Herman Soergel’s portrait), 2018

Artist Heba Y. Amin reappropriates this arrogance in a series of works that take a critical look at colonialist attitudes and turn the Atlantropa’s infrastructural plan on its head. In the video Operation Sunken Sea: Relocating the Mediterranean, Inaugural Speech, the artist portrays herself as the ruler of a fictional nation, re-enacting the speeches, gestures, logic and languages of male authoritarian figures from recent history who have planned or implemented megalomaniac proposals. This time, however, the mastermind in charge of launching the aggressive geoengineering operation is a woman from an Arabic country. With humour and sarcasm, Amin subverts the duality between the Southern and the Northern side of the Mediterranean. Draining and rerouting the Mediterranean sea, her character asserts, would benefit the African continent. It would bring an end to terrorism and the migration crisis, provide employment and energy alternatives, counter the rise of fascism in Europe, challenge the continent’s imperialist stance and finally bring justice to the looted people of Africa.

Heba Y. Amin, Operation Sunken Sea: Relocating the Mediterranean. Inaugural speech, Malta, May 25, 2018 (Excerpt)

Heba Y. Amin, Operation Sunken Sea: Visual Research, Flower Bouquets (video still), 2020

Her grandiloquent speech is resolute and aggressive. Her text is composed entirely of fragments from actual speeches of eight dictators, including Benito Mussolini, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan and Xi Jinping. By plagiarising this presumptuous and patriarchal energy, the artist changes the way these colonialist projects and attitudes are remembered today.

In an interview with ArtForum, the artist explained that Atlantropa was part of a long lineage of similar projects that emerged throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, including a mega-plan to flood the Sahara, presented by different colonial powers. The massive infrastructure project first surfaced in Jules Verne’s 1905 novel Invasion of the Sea which featured European characters who studied the feasibility of flooding a low-lying region of the Sahara desert to create an inland sea and open up the interior of Northern Africa to trade.

Heba Y. Amin, Visions of the Sea I, 2018

Heba Y. Amin, Operation Sunken Sea: Relocating the Mediterranean, Inaugural Speech (video still), 2018

The whole universe Amin created for the project has an old-fashioned, authoritarian and bureaucratic allure. It also uses intriguing graphic symbols. The main emblem of the work series, for example, is a map of the Mediterranean that the artist found in a 10th-century Islamic manuscript, where the Strait of Gibraltar forms the centre of orientation. The map, designed by Persian geographer Al-Istakhri, envisioned the sea as a positive space. A complete reversal of how many European governments envision the Mediterranean today. A stylised version of the map appears in sculptures and flags that flank her desk and speaking column.

I saw the work in several exhibitions. Most recently at the Artissima art fair in Turin. I thought it was high time I mentioned it on the blog.

Other works by Heba Y. Amin: Heba Y. Amin. The toxic legacy that European ideas of progress left on the Egyptian landscape.