The seventh edition of Device_art festival of art, robotics and new technologies closed a few weeks ago at the Museum of Contemporary art in Zagreb.

Branimir Štivić, B E L L O W S, 2021. Photo by Vanja Babic

Anthea Caddy, Miodrag Gladović, 6c6f6e67207468726f77, 2021. Photo by Josip Bolonic

Device_art questions, subverts and adds poetry and humour to the many devices, systems, mechanics and machines that share our life. Like the previous editions of the festival, Device_art 2021 nimbly balanced enthusiasm and criticism; wit and bite; experimentation and function. Moreover, this edition also reflected the current climate of anxiety and uncertainty brought about by a pandemic, an increasingly hard to negate climate meltdown and the uneasy relationship between technology and the more than human living world.

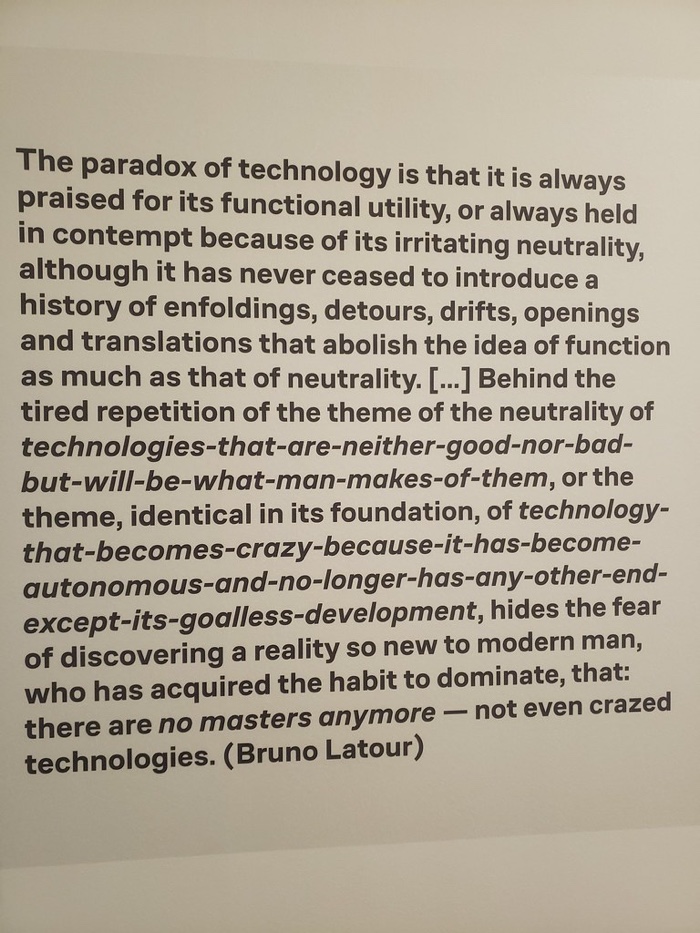

The title of the festival exhibition, Machine Does Not Give Change, alludes to the machines that require exact change to bring about their services. They might be useful but they are uncompromising. The ready-made title also opens up the reflection about the agency of technological apparatuses, their entanglement with social structures and our conflicted attitude towards techniques: we constantly hover between hyping or spurning them. The result is a festival inhabited by bagpipes that breathe when you talk to them, a racing coat that appropriates the visual communication of the whole festival, a nifty hack that generates a virtual traffic jam in Google Maps, two robots battling over a plastic fish, etc. At first sight, the works look just entertaining. However, look closer and you find that they probe issues such as the toxic history of media, the ecological impact of the digital, the obsolescence of electronic devices, our dependence on plastic and other unintended consequences of modernity.

Soll, Your Image Is My Weave and All I Want Is a Racing Coat, 2021. Photo: Jani Mardešić

Right from its first edition in 2004, KONTEJNER | bureau of contemporary art praxis conceived the festival as a research project that would facilitate dialogue between Croatian device art and related art scenes in other countries. After Slovenia and the Czech Republic, Japan, Canada and California, the 2021 edition of the festival united the Croatian and the German scene (or rather the Germany-based scene since so many international artists have chosen to live in Berlin and other German cities.) Here are some of the works I particularly enjoyed during my visit:

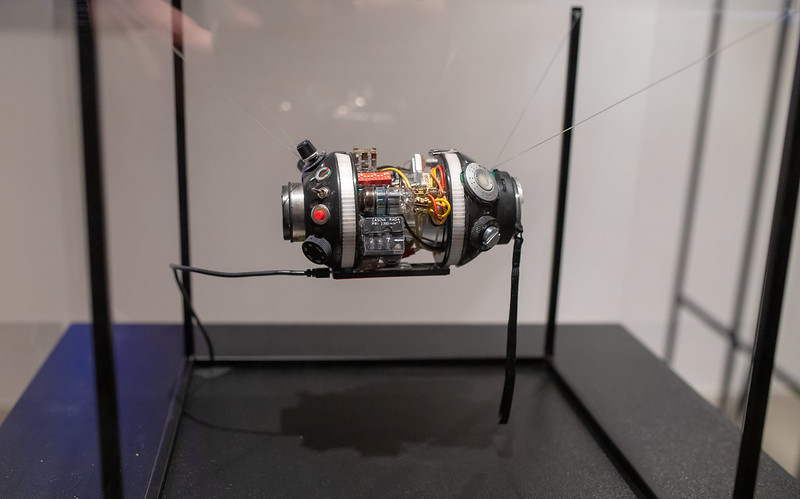

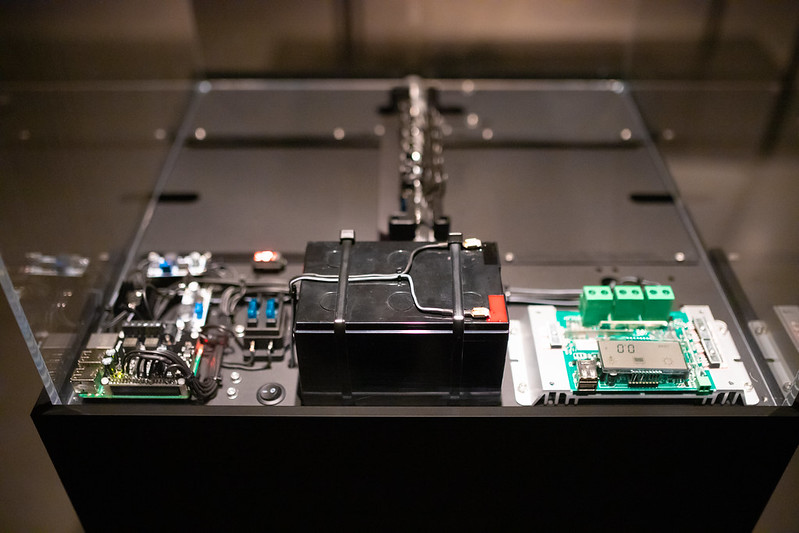

Dominik Gadže, Self-sustainable Computer, 2020, DIY devices. Photo by Josip Bolonic

The larger and more sophisticated the computer, the higher the carbon footprint. While internet service providers and manufacturers of electronics promise that their products and activities are “greener” than ever, our production, storage and exchange of data are increasing exponentially. That’s what economists call the rebound effect or Jevons paradox. The Self-sustainable Computer, by Dominik Gadž, attempts to address the problem. The prototype uses regular rechargeable batteries. The difference is they are charged with the decomposing radioactivity of thorium.

Another reason why the computer never had to be recharged since it was turned on is the device data processing infrastructure. It is similar to the one found in cell phones, except its elements are much bigger – this type of configuration is much more economical because it hardly overheats, while the elements such as the CPU, RAM, etc. are much closer to each other, allowing for speedier communication between them.

The most surprising element of the Self-sustainable Computer is the way it challenges the habits and expectations of the user. Instead of the usual flat surfaces, the interface invites users to manipulate the device, move it around and get a more tangible understanding of the interface.

The prototype might be fairly small and compact but the number of concerns it explores is impressive: more efficient methods of data processing, alternative interfaces and the thorny issue of the role that nuclear energy can play in reducing carbon emissions.

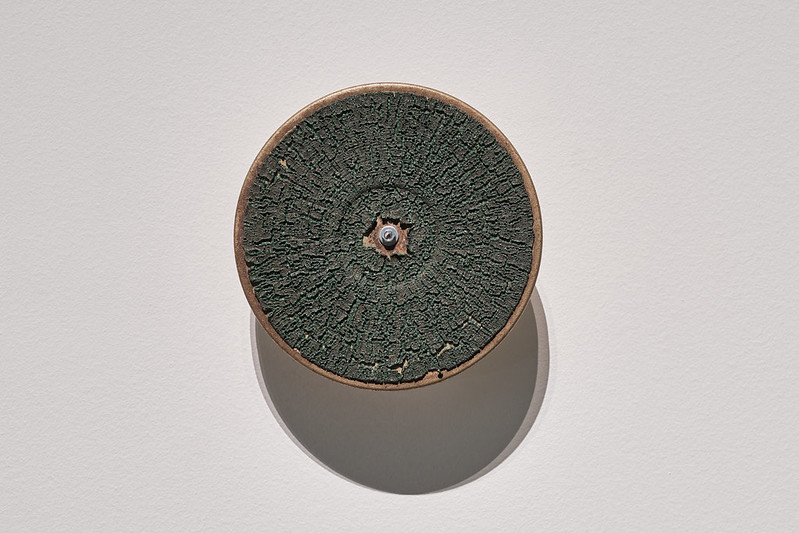

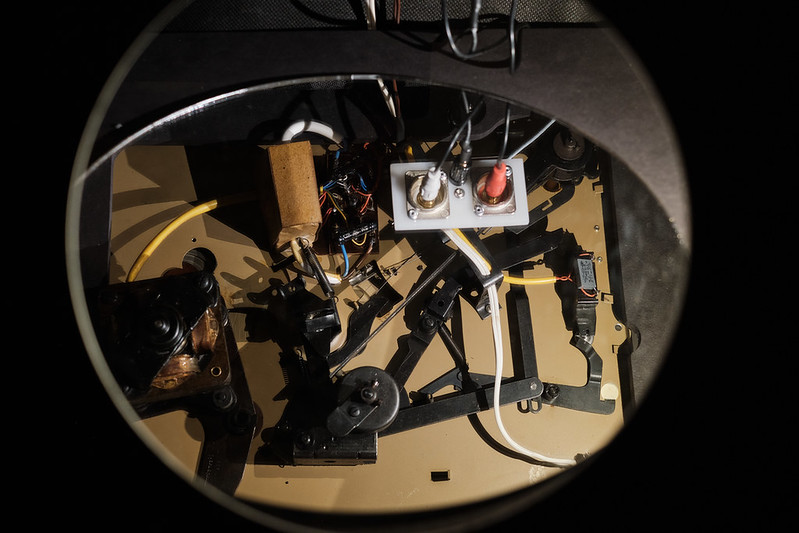

Darsha Hewitt, High Fidelity Wasteland II: The Protoplastic Groove, 2021. Photo by Vanja Babic

Darsha Hewitt, High Fidelity Wasteland II: The Protoplastic Groove, 2021. Photo by Vanja Babic

Darsha Hewitt, High Fidelity Wasteland II: The Protoplastic Groove, 2021. Photo by Vanja Babic

Darsha Hewitt, High Fidelity Wasteland II: The Protoplastic Groove, 2021. Photo by Vanja Babic

Darsha Hewitt, High Fidelity Wasteland II: The Protoplastic Groove, 2021. Photo by Vanja Babic

Darsha Hewitt, High Fidelity Wasteland II: The Protoplastic Groove, 2021. Photo by Josip Bolonic

Shellac looks and behaves like plastic but it is in fact a resin secreted by the female lac insect as a protective shelter for her offspring. The material is used by various industries as a colorant, as food glaze, wood finish, etc. This by-product of the survival strategy of the insect was massively farmed to manufacture the first disks until 1948 when vinyl long-playing records took over. From 1921 to 1928, 18,000 tons of the resin were used to create 260 million records for Europe. In the 1930s, it was estimated that half of all shellac was used for gramophone records.

High Fidelity Wasteland II: The Protoplastic Groove is an immersive sound installation centered around a 1950s era record player that devolves the audible timescale of music from a past when disks were made of shellac.

Rather than rapidly spinning music at the standard 78 rpm, the player slows everything down to a mere 16 revolutions per minute and stretches sound, subtly revealing the impurities, noise and biological origins of shellac records.

High Fidelity Wasteland II is the second chapter in Darsha Hewitt’s trilogy that exposes the long shadow of waste cast by the music industry. Not only does the installation make visible the obsolescence of media, it also fleshes out the gradual dematerialisation of music. That dematerialisation is only apparent: the whole infrastructure and maintenance of servers, underwater fiber optic cables, access points and many the electronic parts that make streaming possible come with their own energy and extractivist prerequisites.

Carolin Liebl & Nikolas Schmid-Pfähler, RE:PLACES, 2021. Photo by Vanja Babic

Carolin Liebl & Nikolas Schmid-Pfähler, RE:PLACES, 2021. Photo by Vanja Babic

Carolin Liebl & Nikolas Schmid-Pfähler, RE:PLACES, 2021. Photo by Vanja Babic

Carolin Liebl & Nikolas Schmid-Pfähler, RE:PLACES, 2021. Photo by Vanja Babic

RE:PLACES is a robot that turns plastic waste from 3D printers into sculptures.

The type of plastic used is PLA, a material made from plant-derived substances like corn starch and sugarcane. It is biodegradable but takes months to decompose. In most industrial recycling plants, PLA is not separated by type and is simply burned, although some industrial composting plants allow for the degradation of PLA within a few months.

To make the most of the energy used for the PLA production, the robot transforms this waste into abstract sculptures.

The extrusion bot moves around autonomously and “decides” where and how to drop the plastic sculptures based on sensor data. By granting the robot a creative behaviour, the artists hint at our own role as earthly actors.

I liked the ambiguity of the work. It shows how a material otherwise associated with cheap throwaway culture can become a valuable source material for artworks. It is light and playful. As the artists explained when I was visiting the show, it looks like the machine is pooping plastic. However, the artists are keen to avoid any temptation of greenwashing robotic art. Bioplastic cannot be melted down and brought into a new form infinitely. With each new cycle, the material loses properties, the viscosity drops and the plastic becomes brittle. RE:PLACES is thus also exploring how the aesthetic properties of the sculptures change with each cycle.

Pfeifer & Kreutzer, L’emur, 2020. Photo by Josip Bolonic

Pfeifer & Kreutzer, L’emur, 2020. Photo by Vanja Babic

L’emur is a kinetic sculpture made of two windscreen wipers that “stroke” an imitation of fur, flattening its hair downwards and then ruffling them upwards, then downwards, then upwards. And so on. It’s hypnotising and strangely soothing.

Yannick Hofmann, Johannes Jensen, Composing on Wheels2020 – 2021. Photo by Josip Bolonic

Yannick Hofmann, Johannes Jensen, Composing on Wheels2020 – 2021. Photo by Josip Bolonic

Yannick Hofmann, Johannes Jensen, Composing on Wheels, 2020 – 2021. Photo by Josip Bolonic

Composing on Wheels reflects a growing concern among media artists: the invisible and intangible carbon footprint of their practice. The installation uses the muscle power of visitors to produce electronic music. The bicycle is connected to belt-driven generators, which power a sensor-controlled device consisting of an energy-efficient single-board computer and several photo-resistors. While it makes the creation and consumption of energy visible, the installation doesn’t pretend to be the solution to our non-renewable resources troubles.

Moritz Simon Geist, Hard Times – Soft Sounds, 2020 – 2021. Photo by Vanja Babic

Moritz Simon Geist, Hard Times – Soft Sounds, 2020 – 2021. Photo by Vanja Babic

During the pandemic, artist Moritz Simon Geist started to create sound machines and filmed them on Instagram.

The small instruments use mundane objects and natural elements. They look as charming and soothing as they sound.

Michail Rybakov, Peekaboo, 2017. Photo by Vanja Babic

Michail Rybakov, Peekaboo, 2017. Photo by Vanja Babic

Michail Rybakov’s mirror won’t reflect your face unless you scream at it.

More images from the Device_art exhibition:

Troika, Terminal Beach, 2020. Photo by Vanja Babic

Troika, Terminal Beach, 2020

Branimir Štivić, B E L L O W S, 2021. Photo by Vanja Babic

Quadrature, LOOP, 2014. Photo by Vanja Babic

Alex Brajković, Drumming 0.3, 2021. Photo by Vanja Babic

The 2021 edition of the Device_art festival was developed by KONTEJNER in collaboration with a group of curators from ZKM | Center for Art and Media in Karlsruhe and was conceived as a dialogue between the German and Croatian “device art” scene.