Art in the Age of Anxiety, edited by writer, curator and cultural historian Omar Kholeif.

Publisher MIT Press describes the book: Every day we are bombarded by information, misinformation, emotion, deception, and secrecy in our online and offline lives. How does the never-ending flow of data affect our powers of perception and decision making? This richly illustrated and boldly designed collection of essays and artworks investigates visual culture in the post-digital age..

Wafaa Bilal, Domestic Tension, 2007

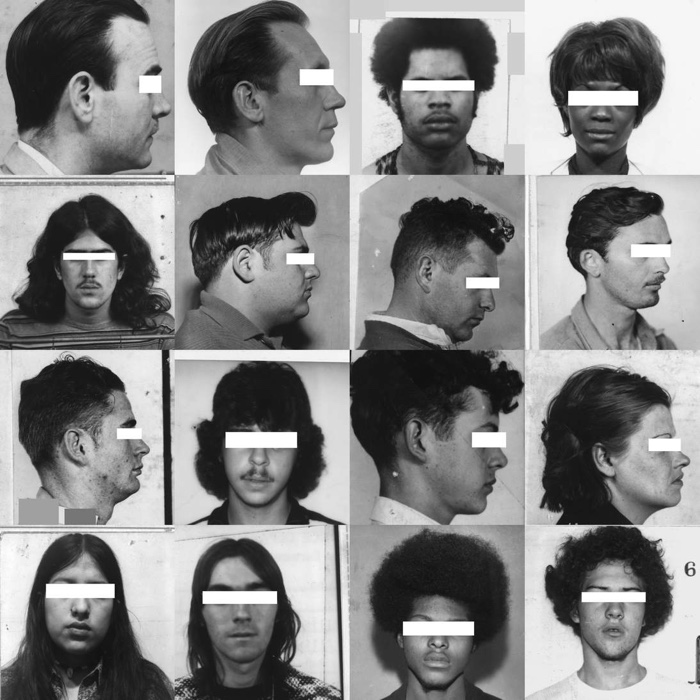

Trevor Paglen, They Took the Faces from the Accused and the Dead… (SD18), (detail), 2020.

The global pandemic and strict lockdowns have left us free to contemplate our anxieties. It’s in this context that I received the catalogue of an exhibition that was prevented from opening precisely because of said pandemic.

The publication confronts head-on the state of perpetual anxiety we find ourselves in and the role that technology plays in amplifying our apprehensions and in fashioning new ones. Information technology has given us greater access to knowledge, greater ease in voicing our opinions, in protesting and resisting injustices (positive impacts that the book also explores.) That same IT has also turbo boosted the spread of misinformation, hate speech, conspiracy theories, polarised views, provided intelligence agencies with new ammunition to spy on us and multiplied the ways private companies can turn us into mere commodities. Even content we should welcome, like information or entertainment, often feels overwhelming. How many free online panels with a stellar line-up can one fit into one day? What does this overload of intellectual stimulation and blue light do to our brains? And should we try and learn to switch off when we’re already self-flagellating for not being productive enough?

Not all essays in Art in the Age of Anxiety are gripping but there are some real gems: Simon Denny writes about how he turned his collection of Margaret Thatcher’s scarves into politically-loaded Patagonia Nano Puff Power Vests. Aruba Khalid explores how digital technology is disrupting money and how this could alter not only the global monetary system but society at large. Marc Tuters and Omar Kholeif have an engaging conversation about online subcultures. Saira Ansari has an essay on grieving online, virtual funerals on WoW and the digital trail we leave behind. Douglas Coupland contributed with both a photo essay featuring spray cans for global warming and a text dissecting the comfort of silliness and other human “superpowers”. As for Cory Arcangel, he wrote about Warhol’s experiments with Amiga software and hardware and about the pop artist’s vision of the straight line between graffiti art and digital art.

Many of the essays are haunted by the pandemic. Or rather by the early days of the pandemic. When all wasn’t jolly Pfizer, projects of antiviral oral drugs and a possible end of the tunnel. Because of that precise timestamp, it will be interesting to see how some of the essays age over time. The initial concept of the exhibition, however, will probably remain relevant and poignant for years to come.

Still, there’s something strangely assuaging in holding in your hands a book that confirms that you might be freaking out but at least you’re in good company.

A couple of works that were part of the Art in the Age of Anxiety exhibition:

Lawrence Abu Hamdan, A Convention of Tiny Movements, 2015-Ongoing

Lawrence Abu Hamdan, A Convention of Tiny Movements, 2015-Ongoing

A Convention of Tiny Movements responds to MIT’s research around visual microphones – devices that can record and then recreate your voice based on micro-vibrations reflected off everyday objects. The extraction of these frequencies has led to a new method of sound recovery, which allows objects to become listening devices.

Although this technology is not yet implemented by spying agencies, the photograph of a supermarket in Beirut suggests all the objects (shown in colour) that can, to date, be successfully used as sound recording devices. The black and white sections of this photo indicate the objects that cannot yet be used as microphones and therefore show the blind or silent spots of this technology.

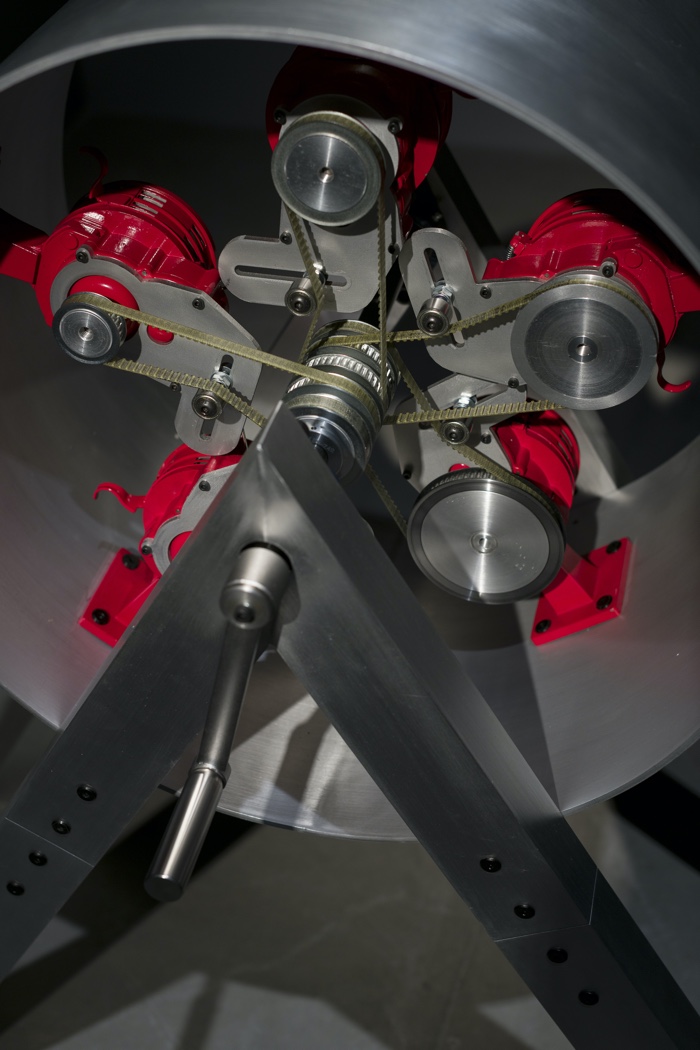

Aleksandra Domanović, Kalbträgerin (detail), 2017. From ‘Votive’, 2016–ongoing. Installation view: Art in the Age of Anxiety, Sharjah Art Foundation, 2020. Photo: Danko Stjepanovic

Aleksandra Domanović’s sculpture Kalbträgerin translates scientific research in breeding certain traits in cattle (such as hornless bulls) into 3D printed sculptures. The calf on the votive stela is a biotech version of the 6th century BC Moschophoros (Calf Bearer), found on the Acropolis of Athens.

Lynn Hershman Leeson, Shadow Stalker (still), 2019

Lynn Hershman Leeson’s Shadow Stalker draws attention to internet systems used by law enforcement that promote racial profiling (Predictive Policing) and to the erosion of individual rights in a time of excessive surveillance and misuse of data.

Jenna Sutela, Nimiia Cétïï, 2018

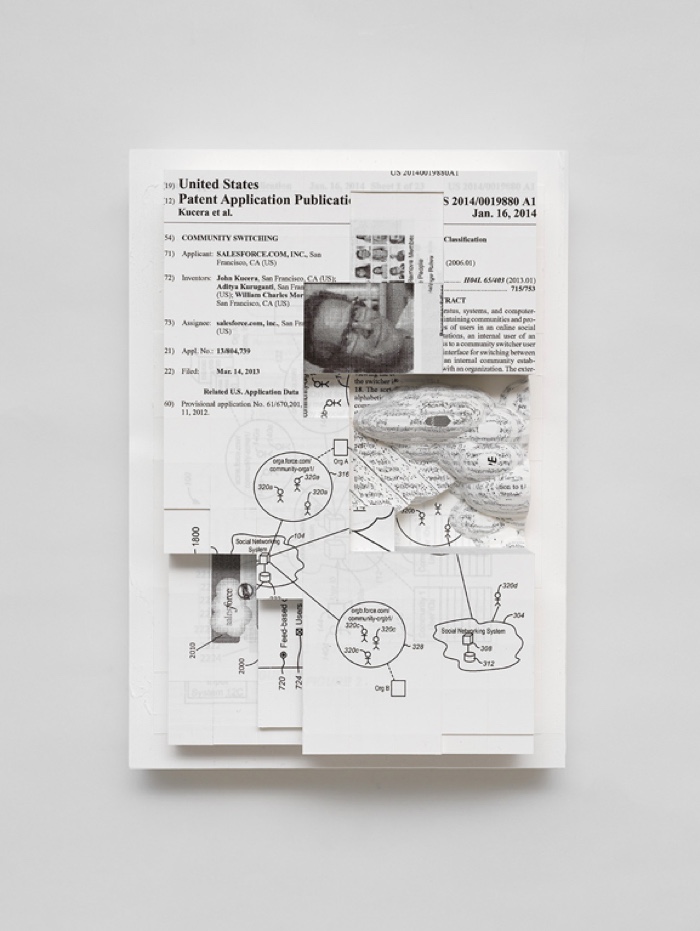

Simon Denny, Document Relief 16, 2019

Electronic Disturbance Theater, Transborder Immigrant Tool, 2007–ongoing

Eva & Franco Mattes, What Has Been Seen, 2017

Eva & Franco Mattes, What Has Been Seen, 2017

Thomson & Craighead, More Songs of Innocence and of Experience (video still), 2013. Installation view: Art in the Age of Anxiety, Sharjah Art Foundation, 2020. Photo: Danko Stjepanovic

Aura Satz, The Wail That Was Warning, 2018