Het Nieuwe Instituut, a museum in Rotterdam dedicated to architecture, design and digital culture, has recently opened an exhibition that challenges visitors to look at the inventive and creative side of cybercrime. What if malware were not just damaging pieces of software but also anonymous works of design?

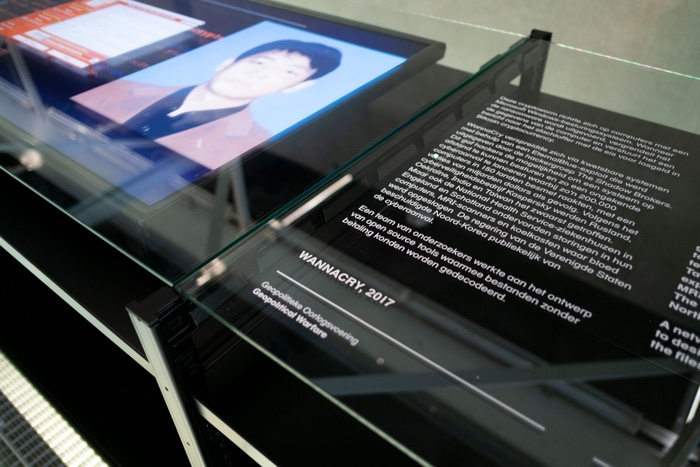

CryptoLocker. Malware, exhibition view at Het Nieuwe Instituut. Photo: Ewout Huibers

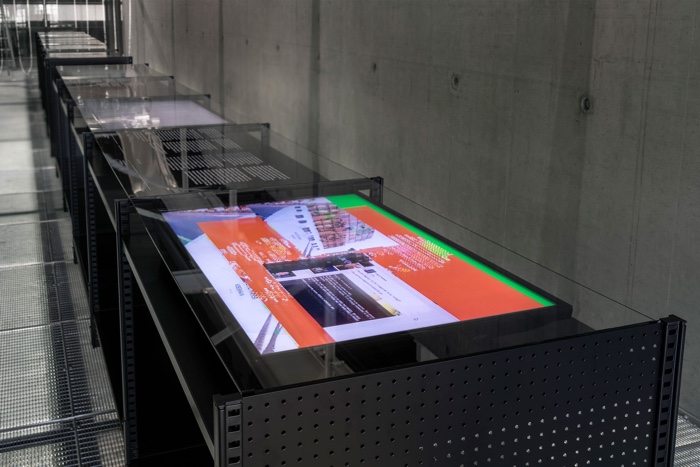

Malware, exhibition view at Het Nieuwe Instituut. Photo: Astin le Clercq

Curated by designer Bas van de Poel together with architect, researcher and curator Marina Otero Verzier, Malware: Symptoms of Viral Infection charts the eventful history of computer viruses. Harmful software started infecting our devices over 30 years ago. They started as experimental pranks and underground activism but they soon became nifty works of social engineering that incorporated the human in the scripting language, exploiting our weaknesses and making us behave as they wished. Nowadays, their playground is politics and warfare. Malware have grown to become painfully sophisticated spying tools and geopolitical weapon developed by governments.

Malware, exhibition view at Het Nieuwe Instituut. Photo: Ewout Huibers

Malware – exhibition about the history and evolution of the computer virus. A video by Marit Geluk

As the exhibition demonstrates, the future of malware is bright. But not for us. We might feel that we, as individuals, are less exposed to virus misdeeds than in the early days but we should not underestimate the Damocles Sword hanging over our head. A depressingly high number of serious ransomware, data breaches, state-backed hacking campaigns and other cybersecurity incidents have already marked 2019 and reminded us that technology has always grown in close connection with conflicts. And as we increasingly rely on AI algorithms, on the comfort of the so-called “smart” cities and on connected medical devices implanted inside our bodies, malware will come back to haunt us personally, invading our private spaces and potentially manipulating our behaviours and emotions.

Kenzero, 2010. Artistic interpretations by Tomorrow Bureau and Bas van de Poel

In her presentation during the opening night, Svitlana Matviyenko, a media scholar and the co-author of Cyberwar and Revolution, highlighted the cultural and strategic importance of malware. She made the bold but pertinent suggestion that internet might seem to have become unfriendly, almost impossible to use, to the point that some have claimed that the internet is “broken”. Maybe, she continued, the internet isn’t broken, maybe it has come to its true realization as a malicious environment. It’s finally reached its perfect stage and we’re not the receiver of the message anymore, we’ve become a relay in the war.

Malware, exhibition view at Het Nieuwe Instituut. Photo: Ewout Huibers

I learnt a lot while visiting Malware. Through its brief but dense history of malicious software, the exhibition not only inform visitors about the many challenges related to security, warfare and geopolitics in times of rapid technological advance, it also invites designers and other creative minds to reflect on the role they can play to counter theses forms of innovative but malignant digital practices.

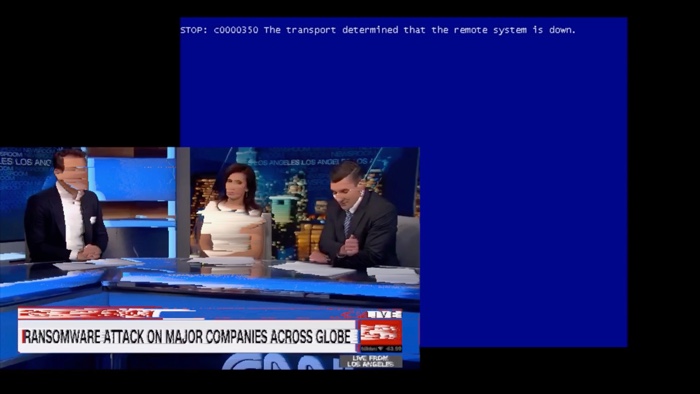

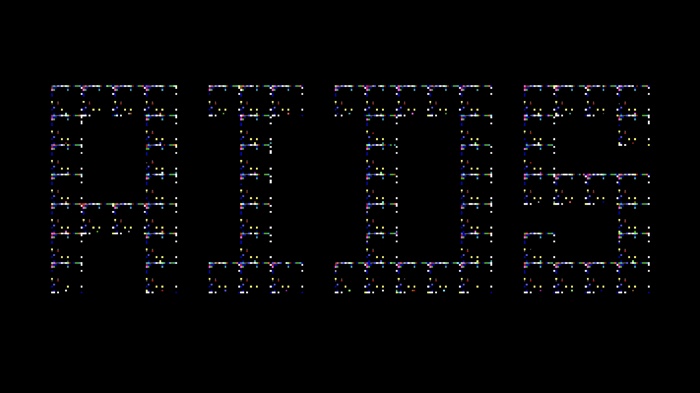

Most of the malware cases highlighted in Rotterdam are illustrated by an artistic interpretation designed by Bas Van de Poel and Bureau Tomorrow. They used screenshot of the viruses, news footage, images of the type of facilities infiltrated and other visual clues to help visitors understand the power and creativity behind malicious software. Here’s a small selections of the viruses exhibited:

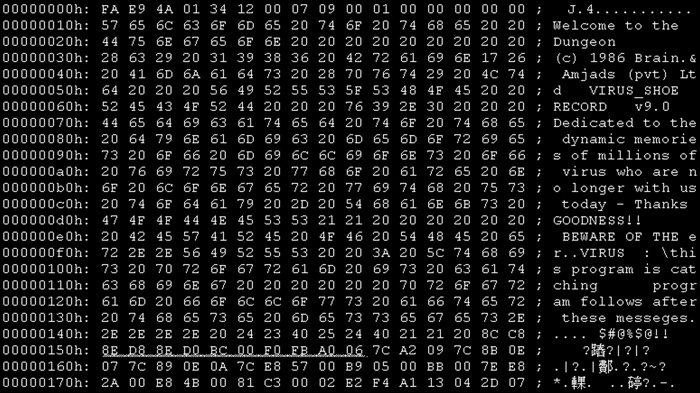

DOS Virus BRAIN, part of the Malware exhibition at Het Nieuwe Instituut

Brain: Searching for the first PC virus in Pakistan. Mikko Hypponen traveled to Lahore to find the authors of BRAIN

Also known as “Pakistani flu”, Brain was created in 1986 by Basit and Amjad Farooq Alvi, two brothers based in Lahore. Considered the first computer virus for Microsoft disk operating system, the code was designed to protect their medical software from piracy. Brain corrupted IBM PCs by replacing the boot sector of a floppy disk. The virus was accompanied by the brothers’ address, phone numbers and a message informing the user that their machine was infected and to call them for inoculation.

The brothers intention was not malicious so they were surprised to receive phone calls from people in the UK, the United States and elsewhere, demanding that they disinfect their machines. Their telecommunications company Brain still exists at the same address. They had to change their phone numbers though.

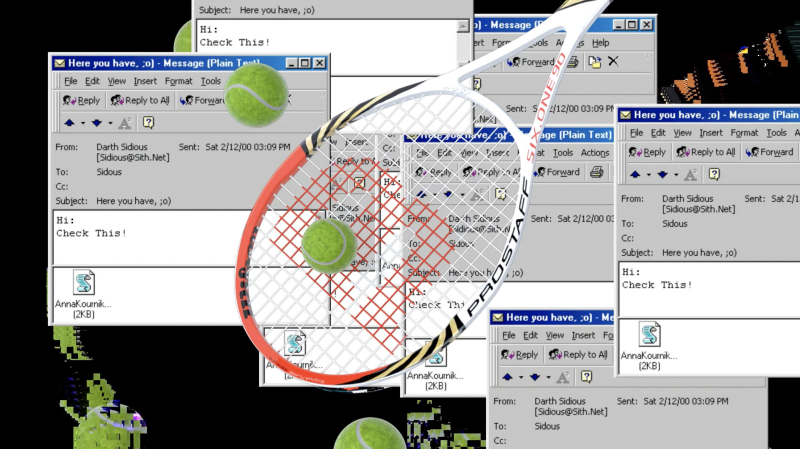

Artistic interpretation of the Anna Kournikova virus by Tomorrow Bureau and Bas van de Poel

The Anna Kournikova computer worm hit computers on 11 February 2001, when some people received a short e-mail that tricked them into opening a file allegedly containing a picture of the Russian tennis player. Millions of them spread the virus in a short time. The designer of the malware, 20-year old Jan de Wit, was caught and sentenced to 150 hours of community service. The mayor of De Wit’s hometown, Sneek, offered him a position at the local IT department, mirroring the case of several hackers who, once caught, were offered lower sentences and even a job if they accepted to collaborate with the FBI.

What makes this virus (maybe we would even call it “clickbait” these days) particularly interesting is that the short statement De Wit posted on a website: “I never intended to harm the people who opened the attachment. But in the end it’s their own fault that they got infected.”

In his talk during the opening night, Jussi Parikka, a new media theorist and the author of Digital Contagions: A Media Archaeology of Computer Viruses, echoed that statement when he suggested that a computer user nowadays who doesn’t know how things work becomes part of the problem.

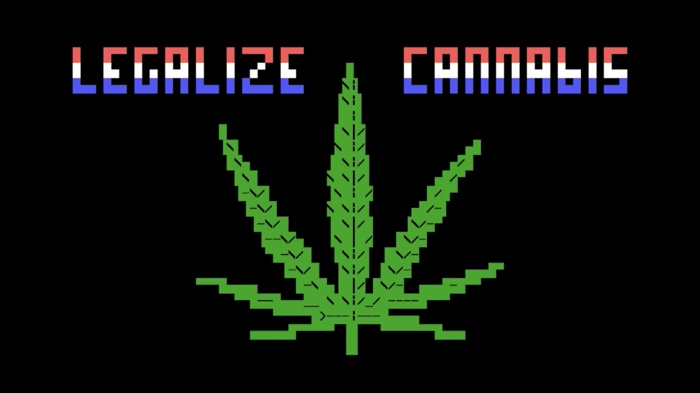

Coffeeshop DOS computer virus, part of the Malware exhibition at Het Nieuwe Instituut

Coffeeshop would have failed into oblivion were it not for the fact that it demonstrated in the early 1990s that computers could be used to make a political statement. One of the earliest manifestations of hacktivism, this DOS virus spread through floppy disks and inserted the text string “CoffeeShop” into infected files, prompting the message “Legalize cannabis” and an 8-bit marijuana leaf to appear on computer screens.

Stuxnet, artistic interpretation. Image by Tomorrow Bureau and Bas van de Poel

Stuxnet, artistic interpretation by Tomorrow Bureau and Bas van de Poel

Stuxnet was a malicious worm that changed global military strategy in the 21st century. Delivered via a USB drive, it was designed to disrupt programming instructions that control assembly lines and industrial plants. Regarded as the first weapon made entirely from code, Stuxnet has been linked to a policy of covert warfare against Iran’s nuclear armament that might have been led by the U.S. and Israel.

Stuxnet paved the way for digital viruses that have a direct impact on the physical world. On nuclear power stations and soon on self-driving cars and every single component of the Internet of Things.

Malware, exhibition view at Het Nieuwe Instituut. Photo: Ewout Huibers

Regin (also known as Prax or QWERTY) was a sophisticated malware and hacking toolkit. According to Die Welt, security experts at Microsoft gave it the name “Regin” in 2011, after the smart and crafty character in Norse mythology.

Designed as a weapon for mass surveillance, Regin captured screenshots, stole passwords, recovered deleted files and intercepted traffic without being easily detected. The data collection had been deployed for targeted operations against government organisations, business, infrastructures, financial institutions and individuals. Its impact and complexity raised suspicions that it was used by NSA and its British counterpart, the GCHQ. The Trojan was reportedly found on the network of telecom provider Belgacom and on a USB flash drive used by a staff member of Chancellor Angela Merkel in December 2014.

Artistic interpretation of Ransomware Pollocrypt. Image: Tomorrow Bureau and Bas van de Poel

In 2015, PolloCrypt silently encrypted all the data on infected hard drives, then demanded that their owner pay a “ransom” of several hundred dollars in Bitcoin to a group of hackers. In case of refusal to pay, the files remained encrypted and the users had no access to them. This ransomware used the logo from Los Pollos Hermanos, the chicken restaurant from the Breaking Bad tv show. The most stressful aspect of PolloCrypt was that it suggested that the money had to be paid as quickly as possible, because the price increased as time went on.

More images from the show:

NotPetya, artistic interpretation. Image by Tomorrow Bureau and Bas van de Poel

Malware, exhibition view at Het Nieuwe Instituut. Photo: Ewout Huibers

DOS Virus AIDS, part of the Malware exhibition at Het Nieuwe Instituut

Malware is the first episode of a trilogy that will explore phenomena that are barely visible but have an impact on our personal space (the next one sounds very promising: it will be about ghosts and real estate!)

Malware, curated by Bas van de Poel and Marina Otero Verzier, remains open until 10 November 2019 at Het Nieuwe Instituut in Rotterdam.