Pratchaya Phinthong; Damián Ortega; Marco Godinho; Nairy Baghramian. ©Blaise Adilon

Apichatpong Weerasethakul, The Vapor of Melancholy, 2014. Courtesy Kick the Machine Films, Bangkok et kurimanzutto, Mexico City

I still haven’t decided how much i liked this year’s edition of the Biennale de Lyon which is still open -but only for a few more days- at the Musée d’art contemporain (MacLyon) and at La Sucrière.

Biennale de Lyon: Floating Worlds is the second episode in a trilogy exploring the “modern”. For this edition, invited curator Emma Lavigne found inspiration in Zygmunt Bauman’s concept of liquid modernity. In the 1990s, the Polish sociologist and philosopher started questioning the use of the term “postmodern.” He suggested “liquid modernity” as a better way to describe the condition of constant plasticity and change he observed in social life, identities and global economics within society. Other influences for Lavigne’s vision included the Japanese culture of “the floating world” (ukiyo) and, more prosaically, the important role that the rivers Rhône and Saône have played in the development of the city of Lyon and its surroundings.

I was expecting these ideas of transience, instability and uncertainties to be translated into powerful works that directly engage with some of today’s most pressing and depressing concerns. I got very little of that. I got plenty of clouds (including a couple of atomic ones), foam, puddles, waves and fountains though. Plenty of poetry and classics of modern art that “converse” with contemporary art pieces.

Fortunately, the biennale also features a surprisingly high number of sound works (always a perk in my book!), extraordinary visual and emotional experiences and, here and there, a couple of more politically-minded artworks.

Maybe my problem is that i should be more open-minded and learn to spend more time again with pieces of art don’t coem with dissent and explicit calls to arms. And maybe a contemporary art event that shies away from politics is more laudable than one that pretends to engage with protests and activism just because that’s what gets people’s attention nowadays.

I suspect that i’m going to keep on pondering on the above for a while. In the meantime, here’s a short list of some of the works i found most in line with my expectations from a contemporary art event:

Doug Aitken, Sonic Fountain II, 2013-2017. ©Blaise Adilon

Doug Aitken, Sonic Fountain II, 2013-2017. © Blandine SOULAGE

I’ll start with the biggest exhibition space: La Sucrière, a former sugar warehouse on the banks of the river Saône. Some of the works were massive and played with the battered and enormous volumes of the ex-industrial space. Doug Aitken’s Sonic Fountain II, which occupies one of the silos of the building, is one of them.

A concrete crater has been dug out of the gallery floor and filled with a pool of milky water that is disrupted by droplets tinkling or cascading from the ceiling onto its surface. The drips and drops are released according to a precisely written score and their sounds, recorded by underwater microphones, are amplified in the space. The experience is incredibly soothing. You could stay there for hours.

Susanna Fritscher, Helices soniques / Flügel, Klingen, 2017. ©Blaise Adilon

Susanna Fritscher, Helices soniques / Flügel, Klingen, 2017. ©Blaise Adilon

Susanna Fritscher fills another of the three silos at the Sucrière with a work that plays with the industrial volume and reveals its intrinsic acoustic properties. Simple white pipes, activated by a rotating motor, behave like propellers and produce different sound pitches and geometries according to the speed of their movements through the air. Faster speed makes for higher pitches and almost horizontal volumes that reach out and almost touch the faces of visitors. Dramatic and slightly disquieting.

Philippe Quesne, Welcome in Caveland, 2017. ©Blaise Adilon

Philippe Quesne, Welcome in Caveland, 2017. ©Blaise Adilon

Philippe Quesne, Welcome in Caveland!, 2017. ©Blaise Adilon

The cave dreamed up by theatre director Philippe Quesne for Welcome to Caveland! squeezes in and outside the pillars of the space. The vast, almost organic entity breathes and inflates at the rhythm of the fans that fill it with air. The plastic ecosystem is made of simple black tarpaulin and its inside is lit up by lamps which luminosity changes over time. But what matters is probably the way visitors use the cave: as a site to investigate, a mysterious stage to take selfie, a vast playground, etc. It’s ridiculous how much i was drawn to that one!

Damián Ortega, Hollow /Stuffed: market law, 2012. ©Blaise Adilon

Damián Ortega hung a nine-metre long submarine above one of the largest rooms of La Sucrière. The sculpture, based on a plastic model of a World War II German Type XXI submarine, is made from industrial food sacks stuffed with salt. Salt escapes from a hole in the sculpture and slowly piles up on the floor. The work is a reference to the recent use of submarines to traffic cocaine along the coasts of South America into Mexico. Instead of being martial and aggressive like the original submersible, Ortega’s vessel is pitiful, deflated and unable to protect its contents from the effects of gravity. Not sure i understand the full reasoning behind this one but damn! it is stunning!

Tomás Saraceno, Hyperweb of the present, 2017. © Blandine SOULAGE

Tomás Saraceno, Hyperweb of the present, 2017. ©Blaise Adilon

A single spider moves across and weaves its web over a ‘hybrid web’ designed by Tomás Saraceno. The vibrations of the spider movements are picked up by microphones and amplified to create the subtle soundtrack of the installation.

Beside the arachnid is a projection of the Large Magellanic Cloud, a galaxy 163,000 light years away from earth. The work thus establishes links between the “miniature universe of a spider’s web” and the vast collection of galactic objects and phenomena.

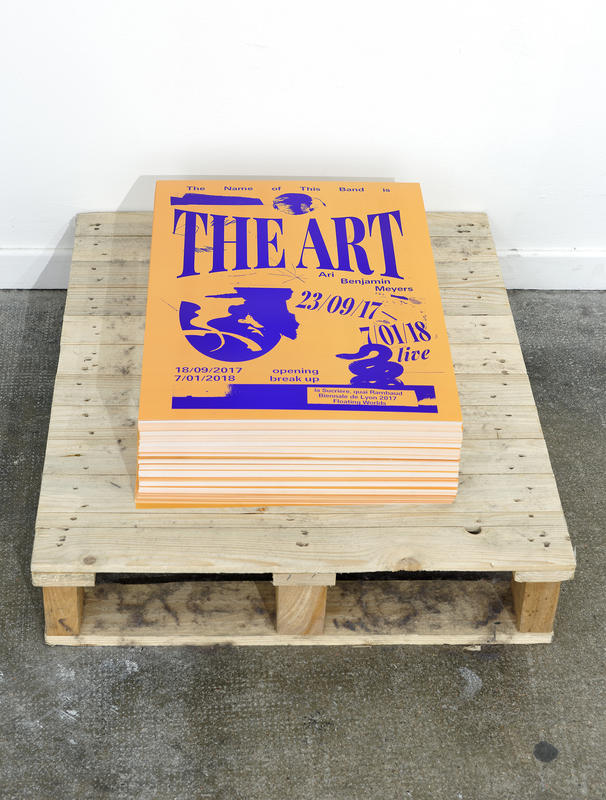

Ari Benjamin Meyers, The Art, 2016. ©Blaise Adilon

Ari Benjamin Meyers, The Art, 2016. ©Blaise Adilon

A disused industrial space is the perfect setting for the rehearsals and performances of a rock band. The Art is an ephemeral group made up of five art students who get together every weekend to play inside one of the exhibition rooms for the duration of the biennial. The group’s stage is surrounded by posters, musical scores, a framed contract that details the terms of the band existence, t-shirts with their “tour dates”, etc. The band and its paraphernalia have all been devised and brought together by composer, conductor and artist Ari Benjamin Meyers. The musicians are free to improvise, modify and interpret the scores as they wish but they are required to disband when the biennale ends.

The Art is part of the artist’s attempts to disrupt the settings of live music events. Meyers wanted live music to free itself from its usual economic model, venues and logic. Talking about his attempt to stage music outside of the traditional clubs and concert halls, Meyers explained: “If I imagine presenting a new work in a gallery context, it’s very different: now it means you didn’t pay, so I don’t owe you anything in that sense, and if you don’t like what you hear or see, leave. And if you do, you can come back the next day, next week, and actually have a relationship with the piece and experience it unfolding over time.”

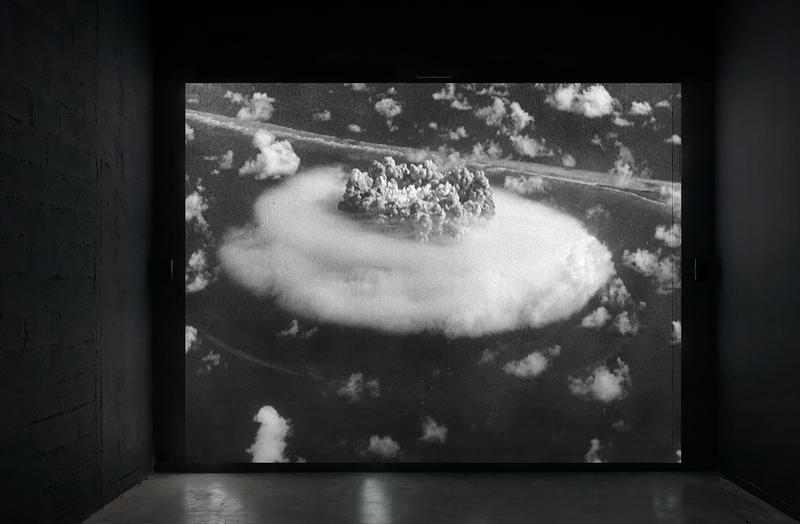

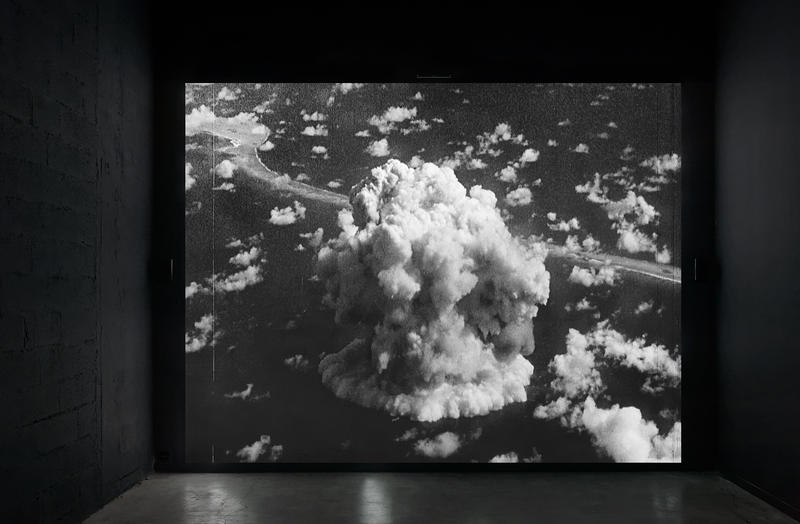

Bruce Conner, Crossroads, 1976. ©Blaise Adilon

Bruce Conner, Crossroads, 1976. ©Blaise Adilon

Bruce Conner, Crossroads, 1976. ©Blaise Adilon

Operation Crossroads was the name of the first two of numerous nuclear weapons tests the United States conducted at Bikini Atoll between 1946 and 1958. Both tests involved the detonation of a weapon as powerful as the atom bomb dropped on Nagasaki.

Because the purpose of the tests was to investigate the effect of nuclear weapons on warships, the U.S. surrounded the site with over 700 cameras, and some 500 camera operators surrounded the test site. Nearly half the world’s supply of film was at Bikini for the tests, making these explosions the most thoroughly photographed moment in history. Yet, the images long remained classified.

In 1976, Bruce Conner asked for the declassified but so far unreleased footage. He then used the archival material to present 23 shots of the same detonation from multiple viewpoints, so that the viewer can experience the test several times over the course of a 36-minute film. We all know these images of the mushroom clouds. By extending the length of this otherwise ultra short moment, Conner reminds us that these images are as visually fascinating as they are terrifying, especially in the light of the recent insults and threats exchanged between Kim Jong-un and Trump.

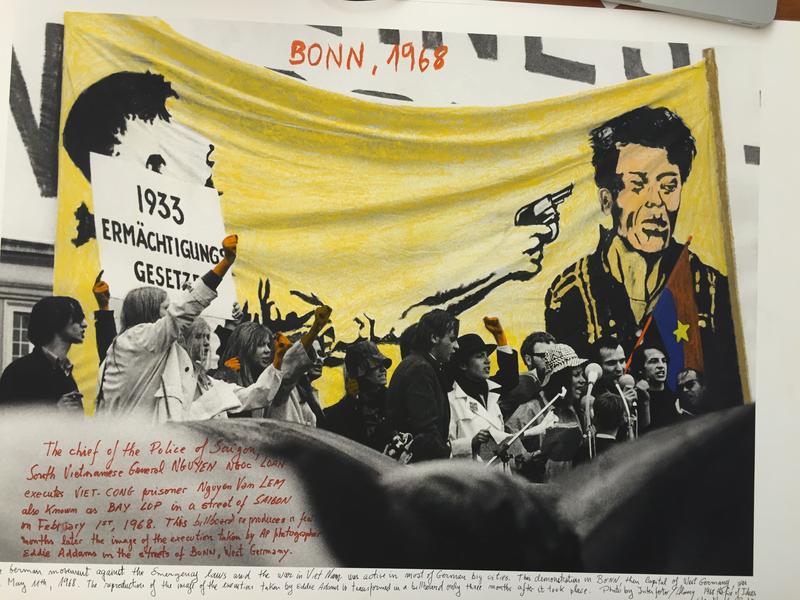

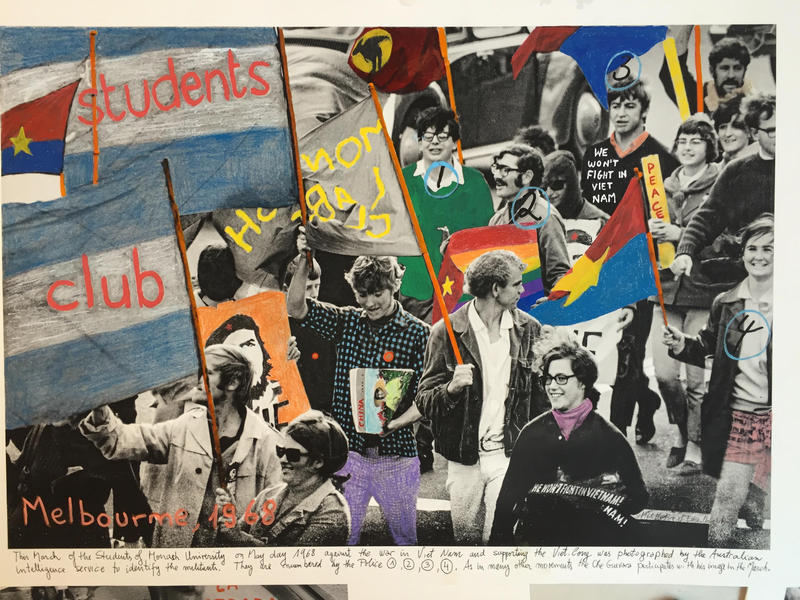

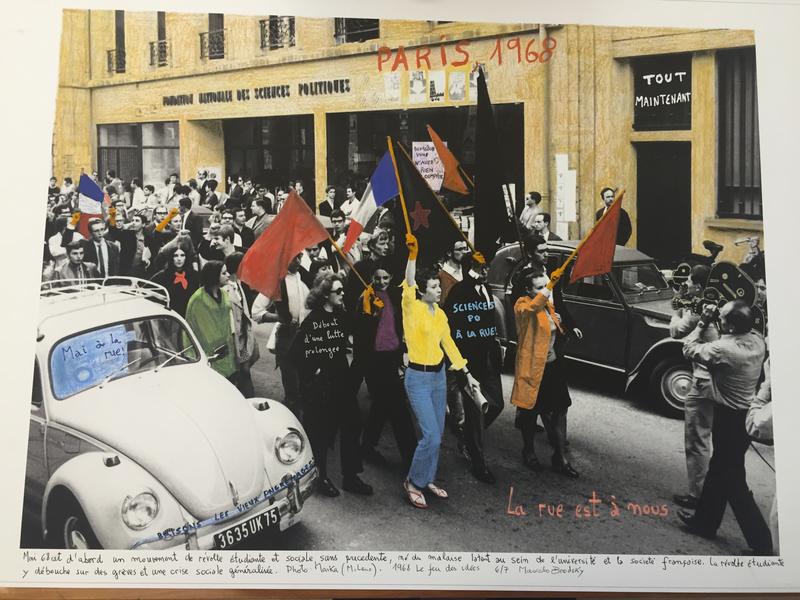

Marcelo Brodsky, 1968 le feu des idées

Marcelo Brodsky, Bonn-Saigon, 1968

Marcelo Brodsky, Melbourne, 1968

Marcelo Brodsky, Paris, 1968

1968 was an important a year for civil rights: young people took to the streets around the world demanding more freedom and brandishing new slogans: No more War, More Political Participation, More Freedom, Power to the Imagination, The Street is Ours, etc. The states often responded with repression and violence.

Marcelo Brodsky spent three years investigating visual archives all over the world, trying to find the most representative images of these street protests and intervened directly on the photos to highlight the protagonists and their demands. The artist, who was forced into exile the military dictatorship in Argentina (1976- 1983), writes: These photographs enable us to approach the facts through the emotions that they (the photographs) elicit. They contain details and also ideas, they tell stories within stories. The way I have treated these photographs underlines the context of the time, those moments of life, the exuberance of the proposals. The ideas of 1968 are more alive than ever and are still relevant to the present.

Now off to the MAC, Lyon’s Museum of Contemporary Art, for other works:

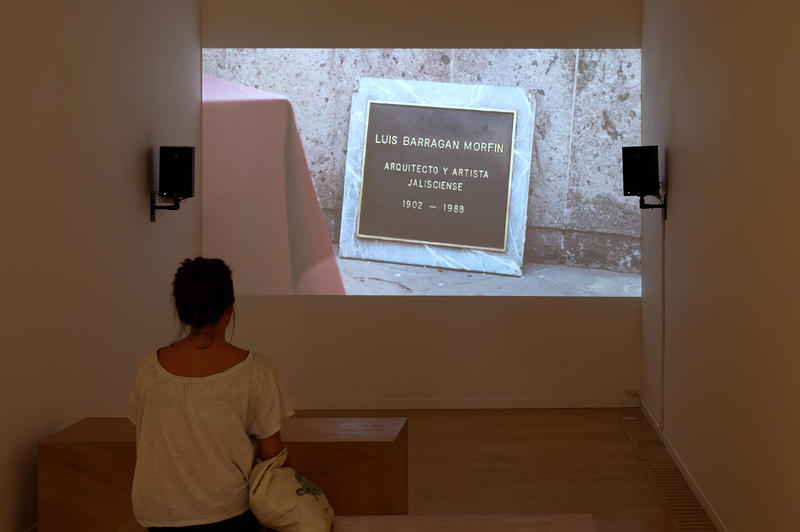

Jill Magid, The Exhumation (video still), 2016

Jill Magid, The Exhumation (video still), 2016

Jill Magid, The Proposal (Trailer)

Jill Magid, The Exhumation, 2016. ©Blaise Adilon

Since 2013, Jill Magid has been exploring the consequences for an artist’s historical legacy of the acquisition of their archive and copyright by a private company. Her research focuses on the Mexican architect Luis Barragàn, whose professional archive -including the rights to his name and work and all photographs taken of it- was bought by Rolf Fehlbaum (the chairman of Vitra and collector of architectural and design iconic works) as an engagement gift for his fiancée, the architectural historian Federica Zanco. For the last twenty years, the archive has been publicly inaccessible.

After being refused access to the archive several times, Magid made the couple a rather astonishing proposal: the repatriation of Barragàn’s professional archive from Switzerland (where it is currently held) in exchange for a ring with a diamond made from some of Barragàn’s ashes: “the body of the artist, in exchange for his works.” Her offer didn’t raise the lady’s interest.

Despite Zanco’s silence, Magid continues her exploration of “the intersection between psychological and legal identity, international property rights and intellectual property, the author and his or her estate.”

David Tudor & Composers Inside Electronics, Rainforest V (variation 2), 2015. ©Blaise Adilon

David Tudor & Composers Inside Electronics, Rainforest V (variation 2), 2015. ©Blaise Adilon

David Tudor & Composers Inside Electronics, Rainforest V (variation 2), 2015. ©Blaise Adilon

Rainforest V (Variation 2), by avant-garde composer David Tudor, is a colourful ecosystem of mundane and often oddly-assembled objects that entices visitors to go from one contraption to the other and immerse themselves into sound. The sculptures hum, whistle, grunt, click, ring and use the exhibition space as a vast amplifier. The distance between the visual perception of an object and the kind of sound added to it participates to the joyful cacophony.

Cildo Meireles, Babel, 2001. ©Blaise Adilon

Cildo Meireles has erected a tower made from 800 of second-hand analogue radios at the entrance of the MAC. The older the radio, the bigger and the lower it is placed in the tower. The top of the tower is thus made of more recent, mass-produced and smaller radios.

The artist tuned each of the radios to different stations and adjusted to the minimum volume at which they are audible, creating a dissonance of incoherent information and music, like a contemporary, electronic Tower of Babel.

Icaro Zorbar, Home, 2017. ©Blaise Adilon

Icaro Zorba works with obsolete technology and equipment he had already used in previous exhibitions to create an immersive, enchanting world. He tinkered with the cathodic tubes of 89 mini tv screens till the image they produce is reduced to one luminous pixel. He then hung them on the wall of one room as if they were a flock of birds, while a record player on the floor quietly plays out a soothing soundtrack.

As he explained in a video interview, Zorbar was inspired by his grandparents who repair everything at their home in Colombia. A poetical nostalgia for a time when objects accompanied us our whole life.

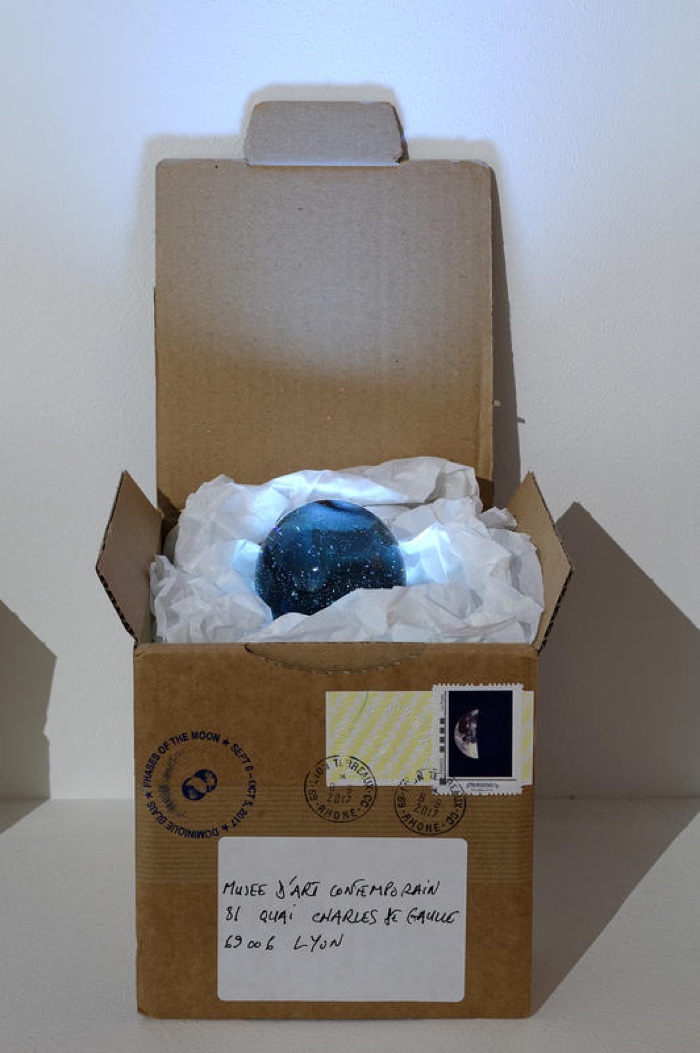

Dominique Blais, Phases of the moon (Full Moon Cycle), 2017. ©Blaise Adilon

Dominique Blais, Phases of the moon (Full Moon Cycle), 2017. ©Blaise Adilon

Dominique Blais, Phases of the moon (Full Moon Cycle), 2017. ©Blaise Adilon

Every day, from 6 September until 5 October 2017, Dominique Blais (who had a number of super interesting works in the biennale) has been posting in the mail a glass representation of the Moon. Each parcel is identical to the last, with the exception of the stamp, which depicts the moon-phase of the postage date. Together, the small globes recreate a complete lunar cycle.

Phases of the moon (Full Moon Cycle) is a kind of mail art that depends on the involuntary collaboration of the postal service and brings together astronomical phenomenon and a not so reliable public service (one of the boxes got lost on its way to the museum.)

Lygia Pape, New house, 2000-2017. ©Blaise Adilon

Lygia Pape, New house (inside), 2000. Photo: ©Paula Pape © Projeto Lygia Pape

New House stands in two, very different locations: overgrown with tropical vegetation in the Tijuca forest in Rio de Janeiro, and in the gallery, in the form of a house which interior appears to have been smashed to pieces.

The piece evokes the progressive destruction of a favela and the marginalization of the people who live there.

More images from the 14th Biennale de Lyon:

Davide Balula, Coloring the WiFi Network (with Power Pink) ; Coloring the WiFi Network (with Pale Yellow) ; Coloring the WiFi Network (with Banana White), 2015. ©Blaise Adilon

Dominique Blais, Untitled (Melancholia), 2016. ©Frederic Lanternier

Anawana Haloba, Leggkhota Za Mazwahule, 2017. ©Blaise Adilon

Apichatpong Weerasethakul, Power Boy (Mekong), 2011. Courtesy of Kick the Machine Films, Bangkok and kurimanzutto, Mexico City

Cerith Wyn Evans, A=P=P=A=R=I=T=I=O=N, 2008. ©Blaise Adilon

Peter Moore, 52 photos, 1963-1978. ©Estate of Peter Moore ©Blaise Adilon

The Biennale de Lyon: Floating Worlds was guest curated by Emma Lavigne. The exhibition takes place across several venues in Lyon until 7 January 2018.