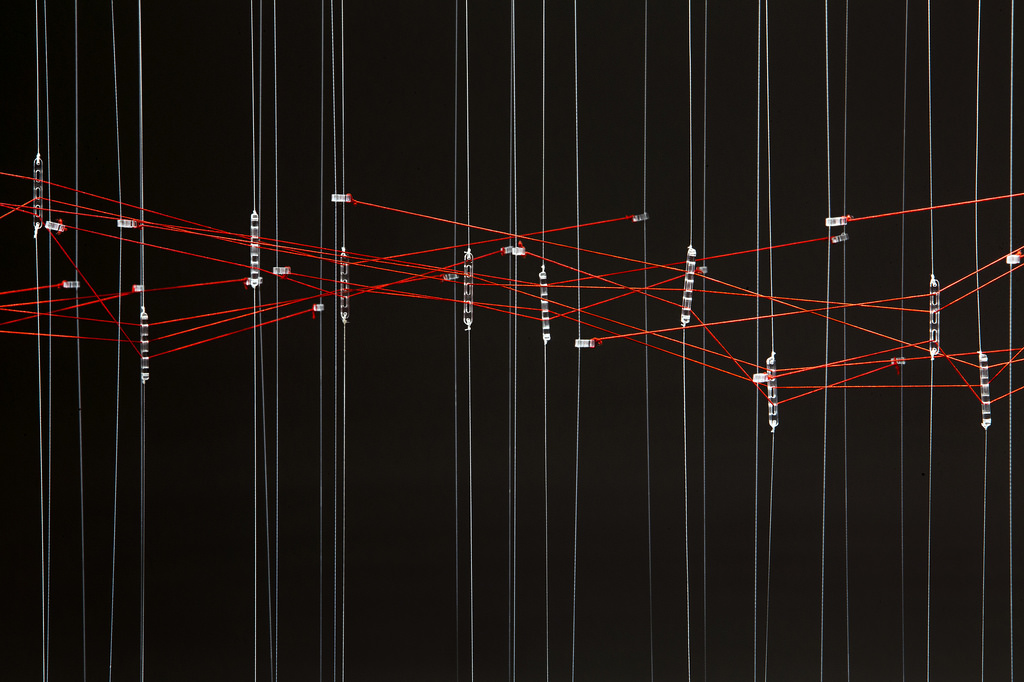

Ralf Baecker, Order+Noise (Interface I), 2016. Photo by Bresadola+Freese/drama-berlin.de for NOME

Ralf Baecker, Order+Noise (Interface I), 2016. Photo by Bresadola+Freese/drama-berlin.de for NOME

I’ve been fascinated by the work of Ralf Baecker ever since i discovered it back in 2009. The way his projects disclose the inner logic and dynamics of machines speaks to the über geek. But you don’t need to be versed in the subtleties of technology to be touched by his installations. Their grace and deceptive simplicity, the way they never quite seem to reveal themselves completely appeal to the aesthete and the amateur of fine craft and enigma.

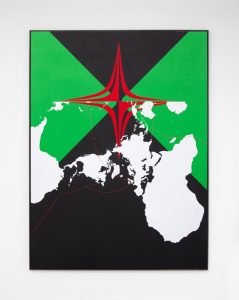

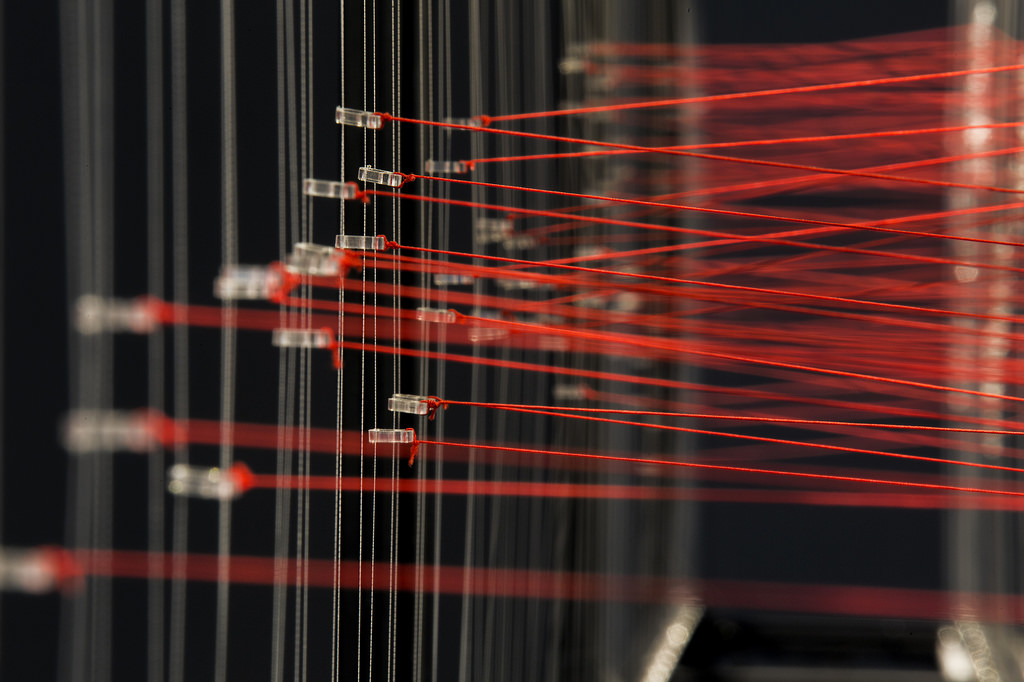

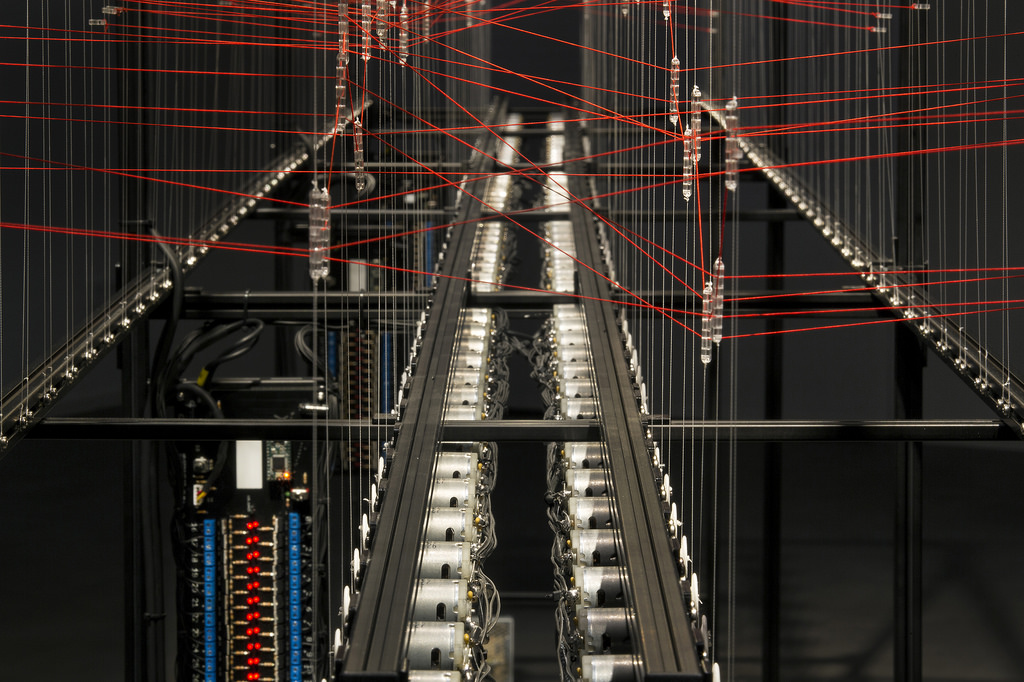

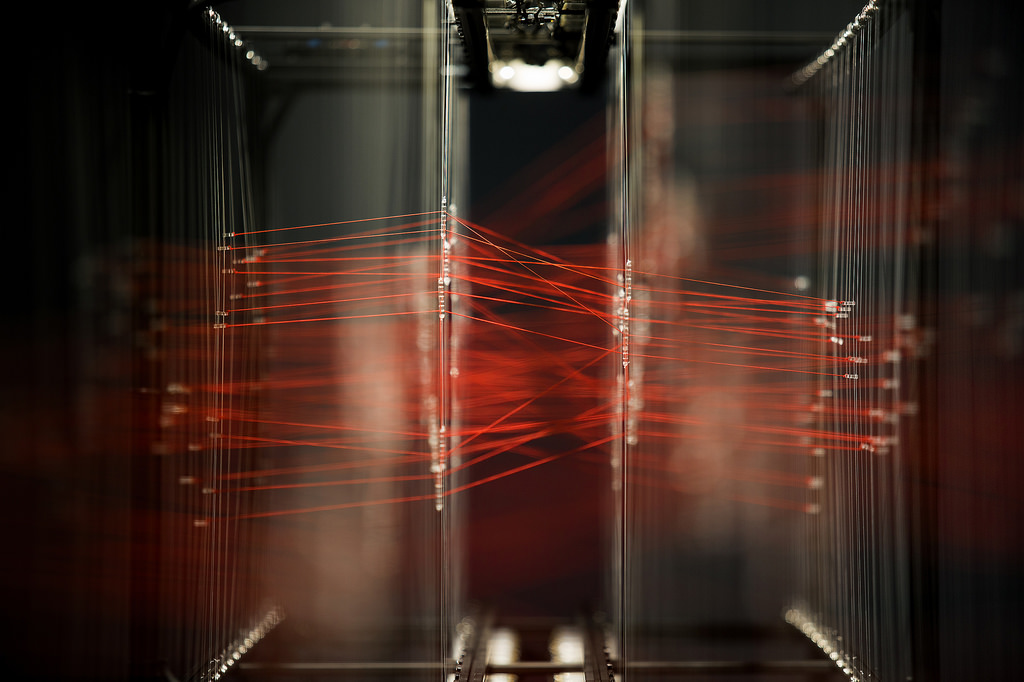

Order+Noise (Interface I), his latest installation currently on view at the NOME gallery in Berlin, is made of motors, strings and elastic bands set in motion by the random signals of Geiger-Müller tubes which pick up the natural ambient radiation of the earth and add an element of chance to the system.

Motors gently hum and pull coloured strings in opposite directions, like in a tug of war. The patterns designed by the network of threads and rubber bands lay bare the struggles, negotiations and fluctuations of the system.

Here, what underlines the aesthetic experience is the materiality by which action produces knowledge, transforming data space into real space. As observers take in the rules, operations and parameters of the work, they gain insight into their perception. The installation’s mechanical workings and network of strings allow us to explore the poetic potential of technology via its materiality, so that Interface I sits on the boundary between an imaginary field and an epistemological condition.

Ralf Baecker, Teaser: Order+Noise (Interface I)

By isolating and zooming in on the abstract mechanisms and systems that are at the core of digital media and information technology, the work of Baecker reveals their otherwise unsuspected rhythms and noises.

I had a Q&A with the artist right before the opening of his show in Berlin:

Hi Ralf! Order+Noise (Interface I) brings our attention to the ambient radiation of the earth. Why were you interested in exploring a geological phenomenon?

The ambient radiation of the earth is only a minor aspect of this work. In case of Interface I it is one way of feeding a system with entropy (chance) and an external rhythm, caused by the unpredictable radioactive decay of elements. I used these kind of “geological” detectors already in previous works, like Irrational Computing (2011) and Mirage (2014), where I measured the magnetic flux of the earth with a magnetometer. What I’m focusing on is the contrast of clean digital machinery and its operations and the crudeness of the geological minerals they are made of. The social and political issues that are connected to the mining of rare earth materials in many countries do not apply to silicon because it is made from quartz sand, which exists in large amounts on earth. With Irrational Computing I was investigating this material layer of contemporary technologies. I build crude digital elements from semi-conducting minerals, like galena, silicon carbide, etc, in its raw form directly taken from the crust of the earth.

Beside this material stack I am interested in the mathematical foundations of these technologies. A closer look reveals a fully closed deterministic system, that is the result of separating mathematics from the world and our experience of it, in order to create a pure formal system. And these are the systems that reach very deep in our daily lives now. Sure, the devices can produce some kind of pseudo randomness, emergent behaviour and we interact with them, but always in the framework of this strict formal system and their protocols.

I don’t think that the machines become more like us, it is more likely that we adapt to the languages of the machines, to become computable. Over the years I tried different approaches to investigates the logic of the internal structures of these systems on one side, and to break them up with more intuitive models on the other side.

In interface these random impulses are used to stimulate two mechanical systems that interact with each other through a network of strings and elastic bands. So the noise acts like a catalyst. From complexity theory we know the principle of self-organisation or “Order from Noise”. Whereby spontaneous order can arise by random fluctuations, like the flocking of birds or in an economy.

Ralf Baecker, Order+Noise (Interface I), 2016. Photo by Bresadola+Freese/drama-berlin.de for NOME

Ralf Baecker, Order+Noise (Interface I), 2016. Photo by Bresadola+Freese/drama-berlin.de for NOME

Ralf Baecker, Order+Noise (Interface I), 2016. Photo by Bresadola+Freese/drama-berlin.de for NOME

The installation explores the interaction between on the one hand, ambient radiation of the earth and on the other one, a set of motors, strings and elastic bands deployed in the gallery. Did you conceive the work as a metaphor about the way natural elements and our man-made industrial world influence each other?

Maybe you allow me to write a few words about metaphors. I’m struggling with the term. I never explicitly have a metaphor in mind, except maybe in Mirage, because my machines are based on symbolic interactions. Sure I don’t avoid hinting to analogies to other systems in other scales. But digital processes are per se not bound to any medium, silicon is just the most efficient and economic one. But every digital circuit can be translated into any medium, like water, air pressure, mechanics etc. I translate and enlarge these processes into other materials in order to allow a spectator to perceive them on an affective level.

Although many of your artworks deal with revealing the materiality of hidden structures and phenomena, there is also something inherently poetical and mysterious about them. At least, that’s the way i see them. What guides the aesthetics and design of your installations?

The aesthetics is always a result of a long experimental process. Usually it starts with a thought experiment that I strip down to a set of minimal components. For Interface I was trying to imagine the tiny and rapid interactions and transactions of a communication between two separate structures. How do they meet in one point and develop a language and get entangled it some kind of dialog. I tried different mechanical approaches, e.g. a push-based system, that turned out yo be too rough and tended to damage itself. There is always a gap between my imagination of a process, its physicality and its actual performance. I usually need a lot of iterations to find a good representation of my initial thought or even adapt my concept to the physical conditions. I started with this method a couple of years ago with Rechnender Raum (2007), I felt a little lost in working only in software, where I already tried to strip the aesthetics down to the minimum in order to offer a sight at the internal/raw aesthetics of these processes before they appear on a screen. But this did not work out for me me because, I still had the feeling that my practice is encapsulated in the logic of these strictly formal machines.

One thing that I have learned is that, making these processes transparent and open does not help to understand them but makes them even more opaque and mysterious. I became very much interested in “magical thinking” in contrast to a chronological “cause and effect” thinking. This thinking blends pretty good with contemporary complexity theory and “system thinking” where one “effect” can not be traced back to a single “cause”.

If we go back to the roots of such machines we will find metaphysical or ideological machines, like the ones of Ramon Llull ones, that are not tools but epistemological instruments.

Another important point, is that I don’t follow the usual separation between process and output. In most of my machines display and process are one, the display is where the process happens and at the same time it is indicating it. Similar to a combustion process, where a fuel and oxygen react with each other and produce an continuous flickering.

Portrait of Ramon Llull

Ralf Baecker, Order+Noise (Interface I), 2016. Photo by Bresadola+Freese/drama-berlin.de for NOME

The research and experiments necessary to the development of the exhibition were carried out within the framework of your research project Time of Non-Reality at the Graduate School of the University of the Arts Berlin. Could you tell us more about this research? And what is this idea of ‘non reality’?

For me the research project at the Graduate School of the UDK in Berlin is a very subjective/artistic genealogy of the digital and technological images. It acts as framework for me to speculate and to experiment. I’m interested in the fundamental concepts, mechanisms and ideas of the digital and the relations to the signs they produce at the other end (e.g. screen).

I stumbled about a quote by Norbert Wiener, in a transcriptions of one of the famous Macy Conferences: “Every digital device is really an analogical device which distinguishes region of attraction rather than by a direct measurement. In other words, a certain time of non-reality pushed far enough will make any device digital.”

“Time of non-reality” could also be understood as the time an electronically charged electronic component (e.g. transistor), or any bistable element, needs to switch from 0 (0 volts) to 1 (5 volts). Ideally, in our logic, there is nothing in between. But when implemented it into the physical, we have these transitions that appear millions of times per second in a contemporary digital device. The internal state of the machines, and what it represents (e.g. an image, a text or a sound), breaks down for a couple of nanoseconds, just to re-establish in the next stable state. The machines are build to blank these transitions, in order to prevent glitches or even a crash. But I’m using this idea to speculate about possible images in between.

As I tried to described earlier these machines are the result of separating mathematics from any empirical evidence, that took place in the early 20th century. The simple axiom “1+1=2” allows us to forget about the apples that we once counted to realise. But these formal systems are now interacting with the world, they produce reality. So my research also explores the gap between an ideal formalized immaterial system and its re-implementation in the world.

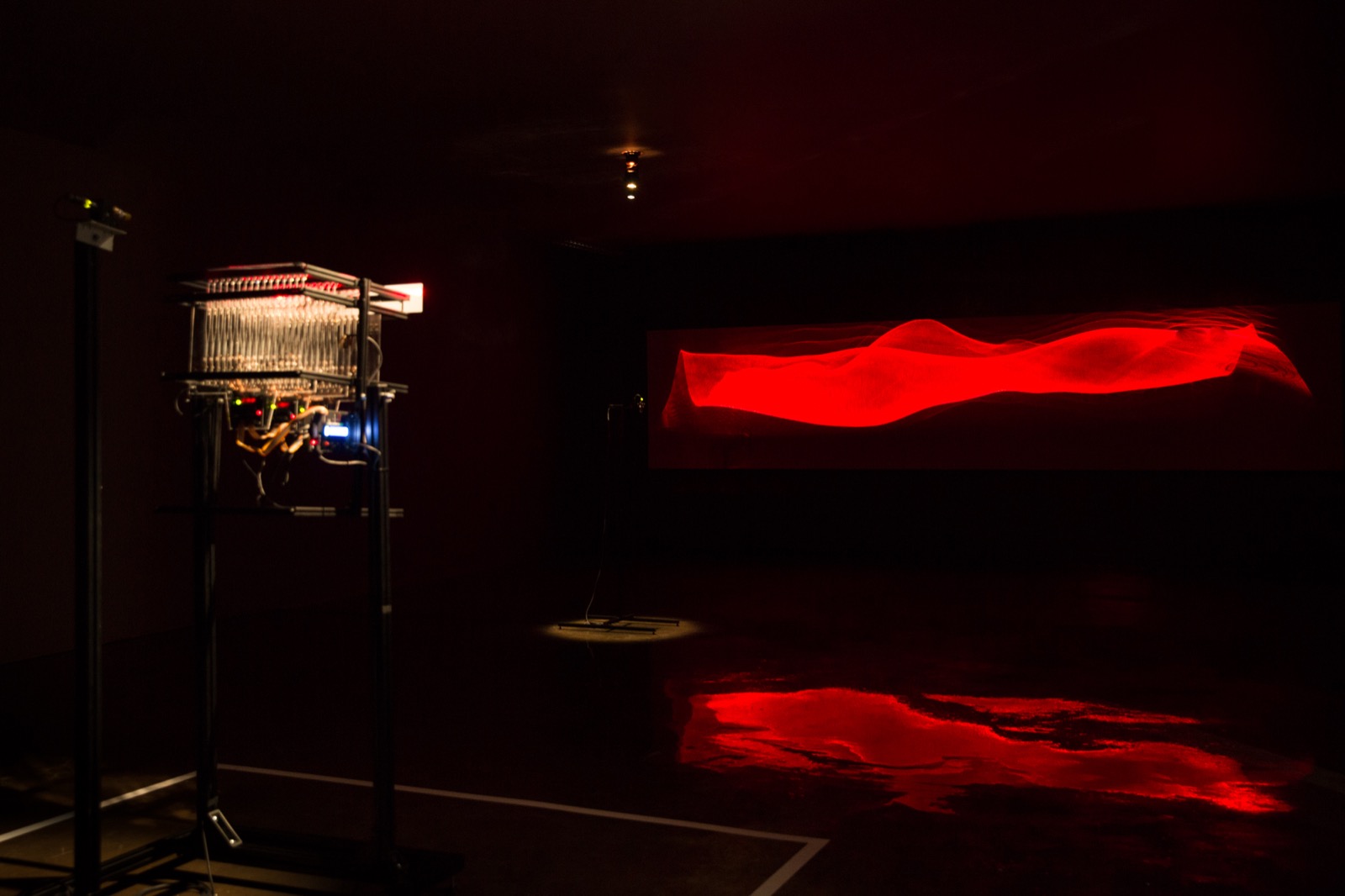

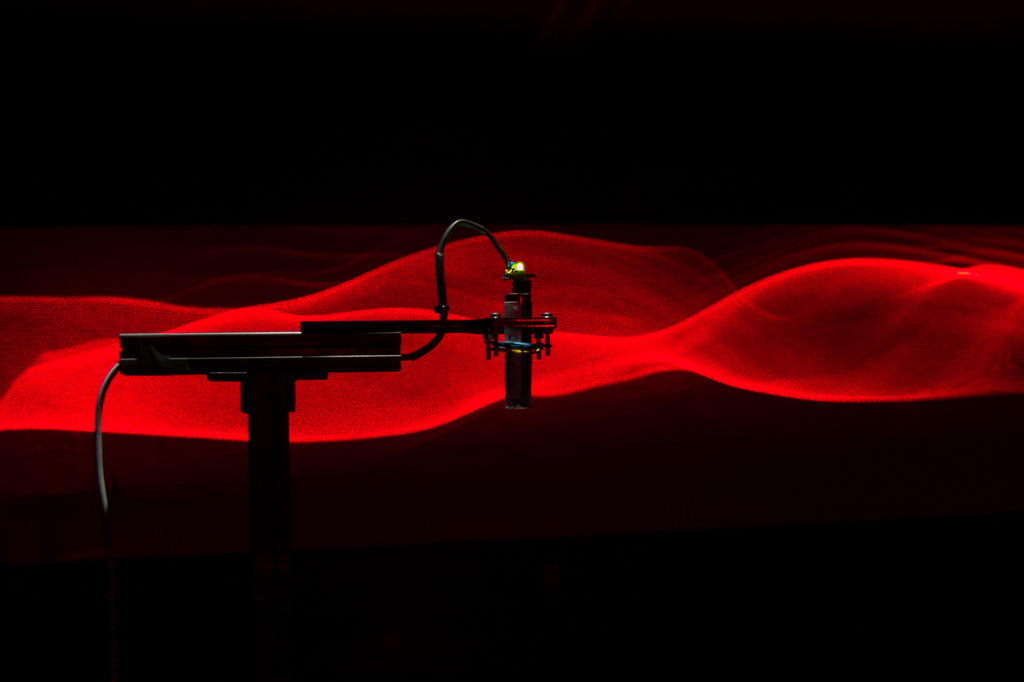

Ralf Baeker, Mirage, 2014. Installation view at Asian Culture Center Gwuangju, for ACT Festival. Photo via Creative Applications

Ralf Baeker, Mirage, 2014. Installation view at Asian Culture Center Gwuangju, for ACT Festival

I was very impressed by Mirage when i saw it at the ACT Festival in Gwangju. I was fascinated by the way the piece is anchored in sophisticated algorithms and Artificial Intelligence but at the same time it speculates about machines that fall asleep and dream. Do you think we should be afraid of machines’ dreams? Doesn’t that make them to freakingly similar to us?

No, I don’t think we have to be afraid. There is still a very big difference between us and artificial intelligence. Most artificial intelligence algorithms are made for one single purpose, they are not universal and their aims and goals are defined by us. What freaks us out is the unpredictability of such systems that arise if their complexity increases. I think this is what we are witnessing right now. We are in the paradox situation that, on one side we are totally excited about the benefits of these technologies and on the other side they evoke a strange feeling of unease. Another kind of sublime, a technological sublime, if we have the enormous world spanning infrastructures in mind they running on.

And because we can’t control our own dreams and hallucinates, i suspect we can’t control the dreams of the machines either. Was it something you experienced while observing Mirage in action? Did the projection and ‘behaviour’ of Mirage surprise you? Did they bring anything unexpected?

The “dreams” or “hallucinations” of the machines are the result of what they have “seen” before. In unsupervised neural networks these “sleep” cycles are used to consolidate the previously learned. They are actually “internal” images, that were not intended to be displayed. Probably everybody knows the images of google’s deep dream. They always include these little puppies, snails or frogs, because these images were part of the training data set. Analogous I can only dream images or things, that I have seen or have imagined before. If a two year old child has never seen or been told about a fox it can not dream it. But the interesting thing is what develops over time, the narration, how our brain constantly tries to make sense of the images that appear and involve them into a plot. Mirage produces plots. It was not trained with static images, it was trained just with a constantly changing one dimensional signal that represents the changes of the magnetic flux of the earth. For earlier experiments, I trained my system with simple sine waves. After a couple of cycles, it was able to recreate sine wave like signals with variations. Mirage recombines the previous sampled data and weaves a new chronology. These idea of machines that create space on time applies to most of my works as well as for Interface.

Thanks Ralf!

Ralf Baecker, Order+Noise (Interface I), 2015. Photo by Photo by Bresadola+Freese/drama-berlin.de

Order+Noise (Interface I) is on view at NOME, Berlin from 23 April until 18 June 2016.

Ralf Baecker is also having a solo show at Kassler Kunstverein, from 13 May until 3 July 2016.