Obfuscation. A User’s Guide for Privacy and Protest, by Assistant Professor of Media, Culture, and Communication at New York University Finn Brunton and Professor of Media, Culture, and Communication and Computer Science at NYU and developer of TrackMeNot Helen Nissenbaum.

(available on amazon USA and UK

)

Publisher MIT Press writes: With Obfuscation, Finn Brunton and Helen Nissenbaum mean to start a revolution. They are calling us not to the barricades but to our computers, offering us ways to fight today’s pervasive digital surveillance—the collection of our data by governments, corporations, advertisers, and hackers. To the toolkit of privacy protecting techniques and projects, they propose adding obfuscation: the deliberate use of ambiguous, confusing, or misleading information to interfere with surveillance and data collection projects. Brunton and Nissenbaum provide tools and a rationale for evasion, noncompliance, refusal, even sabotage—especially for average users, those of us not in a position to opt out or exert control over data about ourselves. Obfuscation will teach users to push back, software developers to keep their user data safe, and policy makers to gather data without misusing it.

Every day, we produce gigantic volumes of data and that data stays around indefinitely even when we’ve move on. We might want to keep personal data as private as possible but that often means opting out from many forms of credit and insurance, social media, efficient search engines, cheaper prices at the shop, etc. It’s perfectly doable of course but it can often be inconvenient and/or expensive.

So Nissenbaum and Brunton see in obfuscation the means to mitigate or even defeat digital surveillance and they provide us with a brief description of it:

Obfuscation is the deliberate addition of ambiguous, confusing, or misleading information to interfere with surveillance and data collection.

The authors also call obfuscation the ‘weapon of the weak’ because this method and strategy of resistance is available to everyone in their everyday life. You don’t need to be rich nor tech-savvy to disobey, waste time, protest and confound.

So now we know what obfuscation is, we might want to understand how it works. At this point, the authors provide the reader with a series of historical and contemporary cases that illustrate various obfuscation techniques. Some of them can immediately be applied to your daily life (speaking in a deliberately vague language, using false tells in poker or swapping loyalty cards with other people to interfere with the analysis of shopping patterns.) Others not so much but all are inspiring. Here’s a quick selection of obfuscating actions:

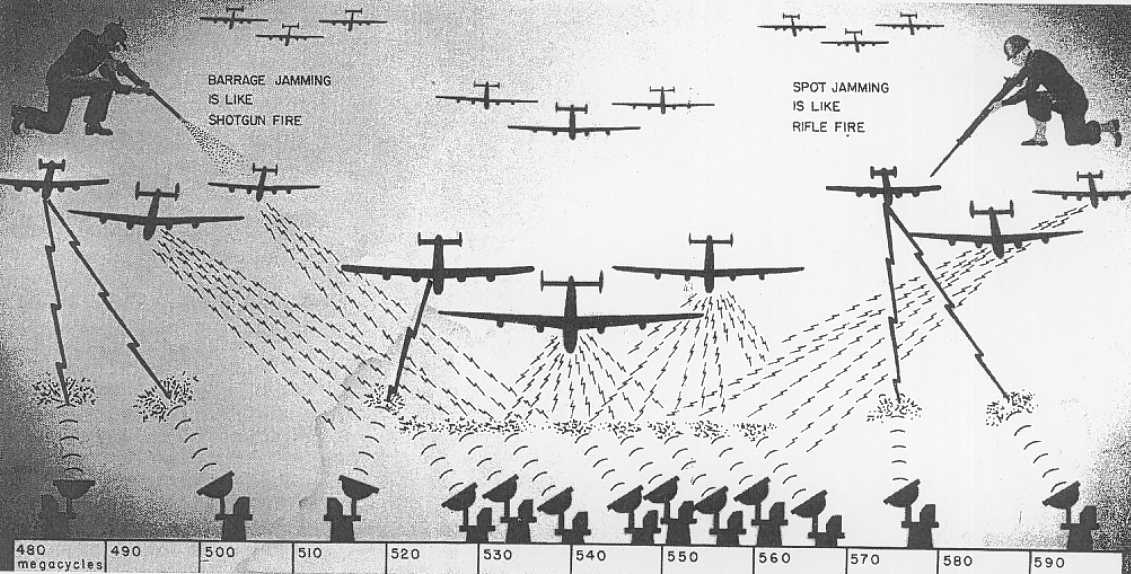

Radar Jamming. Image via Steve Blank

– Chaff is a radar countermeasure in which aircraft or other targets spread a cloud of small pieces of aluminium, metallized glass fibre or plastic, which either appears as a cluster of primary targets on radar screens or swamps the screen with multiple returns. The method was used during WWII to jam the German military radars. All the operator would see was noise, rather than airplanes.

– Twitterbots can fill the conversation on a channel with noise, by using the same # as protesters for example and rendering it unusable.

– “Babble tapes” are digital files played in the background of a conversation in order to defeat audio surveillance.

– AdNauseam clicks on every ad on an online page, creating the impression that someone is interested in everything. The plugin confuses the system and thus protects people from surveillance and online tracking.

– Bayesian Flooding, an idea of Kevin Ludlow, consists in overwhelming Facebook with too much information (most of it false) in order to confuse the advertisers trying to profile the user and the algorithmic machines that are trying to make predictions about his/her interests.

Spartacus film (Dir. Stanley Kubrick) excerpt featuring the “I’m Spartacus” clip, a classic obfuscation moment

The other half of the book attempts to help us understand obfuscation, its role, purposes, limits and possible impact. The authors also spend a few pages exploring whether and when obfuscation is justified and compatible with the political values of society.

Obfuscation: A User’s Guide for Privacy and Protest is an important and straight to the point book that reminds us that, ultimately, we’re up against intimidating asymmetries of power and knowledge. Stronger actors -whether they are corporations, governmental bodies or influential people- have better tools at their disposal if they want to hide something. What we have is obfuscation. It might require time, money, efforts, attention but it gives us some leverage as well as some measures of resistance and dignity.

The book offers 98 pages of dense, informative and never tedious text. I’m glad a publisher as respected and as widely distributed as MIT Press chose to print it.