Ground-up City. Play as a Design Tool, edited by Liane Lefaivre and Döll.

Ground-up City. Play as a Design Tool, edited by Liane Lefaivre and Döll.

010 publishers says: Ground-up City. Play as a Design Tool maps the continuing history of an urban design strategy for play in the city. Liane Lefaivre has developed a theoretical model for tackling playgrounds as an urban strategy. She steps off from a historical overview of play and the ludic in art, architecture and urban design, focusing particularly on the post-war playgrounds realized in Amsterdam as joint ventures between Aldo van Eyck, Cornelis van Eesteren and Jakoba Mulder.

(…)

Ground-up City places the playground high on the agenda as an urban design challenge. It also shows how specifying a generic, academic model for a particular situation can lead to a practically applicable design resource.

The first interesting aspect of the book is that it was written by a theorist and an architecture firm both very keen on exploring the potential of playgrounds as a means to connect people together, to increase a sense of community and to improve the integration of immigrants into the city.

Liane Lefaivre is Professor and Chair of History and Theory of Architecture, University of Applied Art, Vienna, and Research Associate at the Technical University of Delft. The architecture firm Döll – Atelier voor Bouwkunst has developed a practice where creativity and innovation are deployed in order to tackle the design task in an undogmatic way.

Lefaivre has been investigating playgrounds for years, tracking the archive of urban playgrounds Aldo van Eyck had told her about before he died, setting up an exhibition about playgrounds and design for children at the Stedelijk museum in 2002, and writing numerous books on architecture, playgrounds and van Eyck.

Bertelmanplein, 1947 (image)

Bertelmanplein, 1947 (image)

The legacy of Van Eyck pervades the book. The Dutch architect is famous for having designed the playgrounds that almost everyone who grew up in Amsterdam during the ’50s, ’60s and ’70s have played in.

In 1947, the young architect was asked to design a small public playground for Bertelmanplein, a residential area in the Dutch capital. Van Eyck designed a sandpit bordered by a wide rim. He adeed four round stones and a structure of tumbling bars. Bordering the square were trees and five benches. Van Eyck also designed the playground equipment with the objective that it could stimulate the minds of children. The first playground was a success. Many playground commissions followed and Van Eyck adapted his compositional techniques to each site.

Of the 700 playgrounds realised by van Eyck between 1947 and 1978, 90 still maintained their original layout in 2001, though sometimes equipment designed by others had been added. With the playgrounds, he had the opportunity to put the needs of the child and neighbourhood democracy at the centre of town-planning and urban renewal.

Playgrounds are hardly ever taken seriously in urban projects, at least not as much as car parking or street density for example. Besides, the emphasis is usually on safety rather than spontaneity and creativity.

Pink Ghost by Périphériques

Pink Ghost by Périphériques

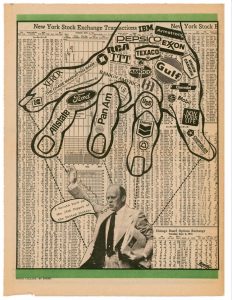

In their chapter about “The Nature of Play”, Döll explains that There is a need for an inspiring alternative that cultivates the potential of homo ludens in an urban context. They set out to demonstrate that the city is already full of playful opportunities by listing some of the most inspiring examples of the re-appropriation of public space by city dwellers: Ingo Vetter’s exploration of Urban Agriculture, free-running, urban golf, street football, rockabilly fans gathering for dance sessions in Tokyo parks on Sunday afternoons, Stadtlounge in St Gallen by Pipilotti Rist and Carlos Martinez, a blue house, Pink Ghost in Paris by Périphériques Architectes, etc.

Stadtlounge (image)

Stadtlounge (image)

Lefaivre then kicked in again with a long and fascinating chapter on the place of play, in particular in the art world, from XVIthe century Dutch paintings to Carsten Höller’s Test Site at Tate Modern. Another focus of the chapter is the history of post-war playgrounds, in particular in Amsterdam.

Lefaivre and Döll had the opportunity to apply their ideal of top-down (driven by the citizens themselves) playground design in a study they realized in two urban redevelopment areas in Rotterdam. Oude Westen in the inner city and Meeuwenplaat in Hoogvliet, both defined as “multicultural neighbourhoods” experiencing social problems. They asked children to give them a tour of their neighbourhood, to take pictures of anything in their area on which they had a positive or negative opinion and to report on how and where they play. See Döll, Work / The World is My Playground.

Image: Dölll – Atelier voor Bouwkunst

Image: Dölll – Atelier voor Bouwkunst

The study has received much interest in the field of public space and play but its materialization into policy and practice is still accompanied by a big question mark.

An interesting appendix is the one made of the interviews carried out by Lefaivre with 2 artists and a curator whose practice involves a particular attention to play: Dan Graham, Erwin Wurm, Jerome Sans.

I picked up that book without thinking too much while i was in my favourite Berlin bookshop, it followed me reluctantly in my suitcase and i only opened it the other day because i was stuck in a hotel room without internet. It might have been one of the very first times that i said “thank you” to the evil and capricious spirits that govern internet connections. Ground-up City is an inspiring little book.

More playground: Playful Parasites, A playground under the table, Playing with urban geography, etc.

Image on the homepage: Daniel Ilabaca does a cat balance, by Jon Lucas.

And one for the road: