A few days ago, i visited the National Museum of the Mountain in Turin. Located “on Monte dei Cappuccini, the Museo Nazionale della Montagna “Duca degli Abruzzi” commands splendid panoramic views of a large sweep of the Alps and the city of Turin below,” its website says. The view is indeed imposing (as my crappy shot below will attest) and the presence of the mountains nearby makes the current temporary exhibition Post-Water all the more affecting. The title sounds like a threat. Is any life even possible in a post-water world?

Francesco Jodice, Aral, Citytellers, 2008

It’s difficult not to contemplate the possibility of an arid future when you realize how much climate change is affecting the Alps. Snow season is shortening; tourism relies more than ever on artificial snow to keep its industry prosperous (which rather ironically further depletes water reserves); glaciers have shrunk to half their earlier size, and by the end of the century all the Alpine glaciers, with a few exceptions, may well have melted away. The consequences are rock falls, more landslides and even national borders that need to be redrawn (as Studio Folder’s Italian Limes demonstrates.)

The art show, curated by Andrea Lerda, explores the ecological and socio-political issues that accompany the water crisis. The works of about twenty artists are accompanied by photos from the museum archives and by a series of texts written by scientists for the exhibition. In her contribution, for example, expert in Atmospheric Physics Elisa Palazzi explains that the water emergency concerns each of us. The global warming conditions that are having such devastating effects on the nearby glaciers are affecting the rest of our planet. Higher temperatures have led to an increase in water evaporation from the oceans and the soils. This higher concentration of vapour in the atmosphere has brought about more intense rainfall and an increase in the risk of fire and droughts. This in turn will have (and is already having) an impact on biodiversity as well as on agriculture and economic systems upon which many human activities depend.

We already know all that and more of course. And yet, what are we doing? Hopefully, the works selected for the Post-Water exhibition will drive us to reflect on our individual responsibility and incite us to call for more governmental action to address climate change.

Here’s a quick tour of the works i found most inspiring. And alarming:

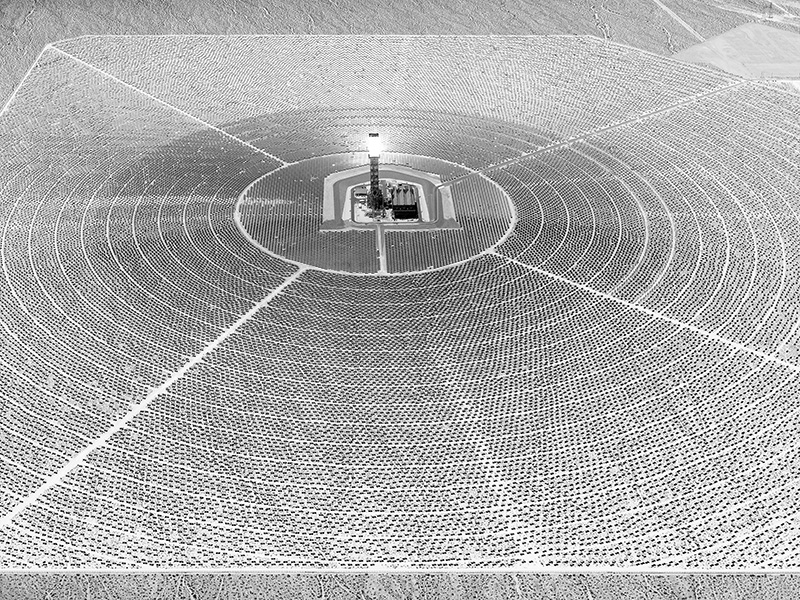

Olivo Barbieri, Ivanpah Solar Electric Generating System CA (from the series “American Monument and Monument”), 2017

Inaugurated in 2014, Ivanpah is the largest thermodynamic solar power plant in the world. Located in the Mojave desert in California, the massive complex deploys 173,500 heliostats and is able to meet the needs of about 140,00 homes.

Despite its very low impact in terms of emissions, the plant raises a number of environmental concerns. One of them is the enormous amounts of water that Ivanpah, located in a drought-prone state, requires to cool its infrastructure. The solar thermal plant is the testimony that there is no quick fix to our energy crisis.

Francesco Jodice, Baikonur, 2008

Francesco Jodice, Aral, Citytellers, 2008

Francesco Jodice, Aral, Citytellers, 2008

Francesco Jodice, Aral_Citytellers (excerpt)

Back in 1954, the Soviet Union turned the Vozrozhdeniya island in the Aral Sea into a classified military town, a secret base for testing chemical and bacteriological weapons. By the 1960s, the island began to grow in size as the sea around it was drying up. Starting in 1959, the Soviet government decided to divert the course of its two tributaries to irrigate a large area in central Asia and introduce the cultivation of cotton. It turned out to be a tragic engineering mistake. The area is now an ecological disaster, former fishing towns have become ship graveyards and the Aral Sea has declined to 10% of its original size.

Today, the Vozrozhdeniya island is one of the most contaminated sites in the world. The receding sea has left plains covered with salt and toxic chemicals resulting from weapons testing, industrial activity, and pesticides and fertilizer runoff. These substances form a toxic dust that winds spread throughout the region. Local communities are suffering from a lack of fresh water, poor quality crops and health problems.

The other element of this devastating Cold War scientific-military experiment is the Baikonur Cosmodrome, located at the East of the Aral Sea, by the city of the same name. Although the city is in Kazakhstan, it is still administered by the Russian Federation. It is from this remote area that humans first sent a satellite, an animal and a man into orbit. The site not only constitutes a geopolitical Russian invasion in Kazakh territories, it is also littered with debris and trash from space missions and experiments, adding to the general feeling of abandonment and contamination of the region.

In Aral_Citytellers, artist Francesco Jodice explores the social, geopolitical and environmental aspects of life in the Aral region. The film is part of the Citytellers trilogy which explores future social conditions in Dubai, Aral Sea and Sao Paulo, areas which are going through drastic geopolitical changes. The film is a video essay, a documentary and a work of video art at the same time. It combines unhurried rhythm, spellbinding images and very relatable characters.

Frank Hurley, By early Spring the Endurance is in a hopeless situation, 1916 (Silver bromide gelatin print from the original negative)

A century ago a ship sank beneath the ice of the Weddell Sea off Antarctica. Polar explorer Ernest Shackleton and his 27-man crew had planned to cross Antarctica from coast to coast. But after a six-day gale in January 1915, the Endurance became trapped in ice in the Weddell Sea. The ship would remain trapped in the ice for 10 months until the crushing forces of the ice eventually breached its hull.

Australian photographer Frank Hurley recorded the last days of the Endurance and the crew’s struggle to stay alive.

Hurley figured out how to take pictures in the dark, without artificial lights. He would light a flare, holding it with one hand to illuminate the scene while taking a photo with the other. His photo of a ship literally frozen in the ice reminds us how different the situation is today. The ice is melting faster than ever, the region, once regarded as inhospitable and dangerous, has become a tourist destination and a place to observe the evidence of climate change.

I read this morning that researchers embarked on an icebreaker are hoping find the wreckage of the lost vessel later this week.

Adam Jeppesen, Ar Chalten I (from the series Folded), 2014

Adam Jeppesen travelled for 487 days, from the north pole to the Antarctic with a photo camera as his sole companion. He documented the vast expanses but it is the materiality of his images that best embodies the landscapes he encountered.

He printed his pictures of majestic glaciers onto rice paper and then folded them. The result are large-scale images that look fragile and are creased like maps. They offer a poignant contrast to the seemingly everlasting appearance of the glaciers.

Mario Fantin, Expedition to the South-East Greenland: ethnographic and archaeological mission, 1966

In 1966, alpinist and documentary maker Mario Fantin made two trips to Greenland. The photos he took to document the adventures are now testimony of a constantly changing world. According to climate model predictions, sea ice in the Arctic could have disappeared in summer by 2040. Less conservative models and recent satellite images, however, suggest that it will come before 2020. The accelerating melting of the ice, year after year, will have a dramatic impact on the climate system. It will also open up new routes for the shipping and oil industry and thus an intensification of pollution in the region.

More works and images from the exhibition:

Ana Mendieta, Ocean Bird (Washup), 1974

Laura Pugno, A futura memoria, 2018

Bepi Ghiotti, unknown source, Bali, 2015

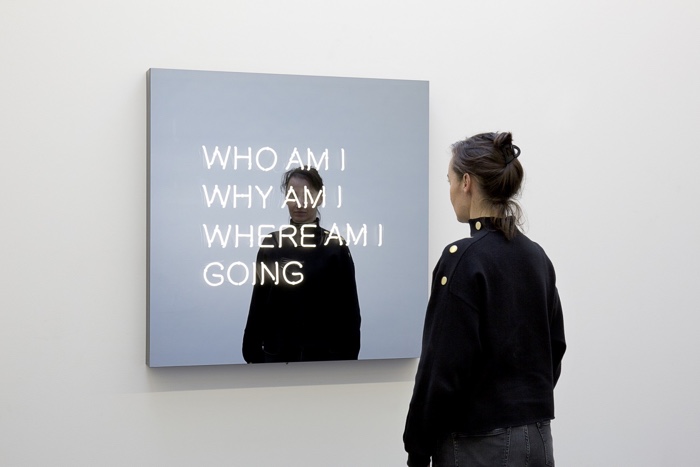

Jeppe Hein, Who Am I Why Am I Where Am I Going, 2017

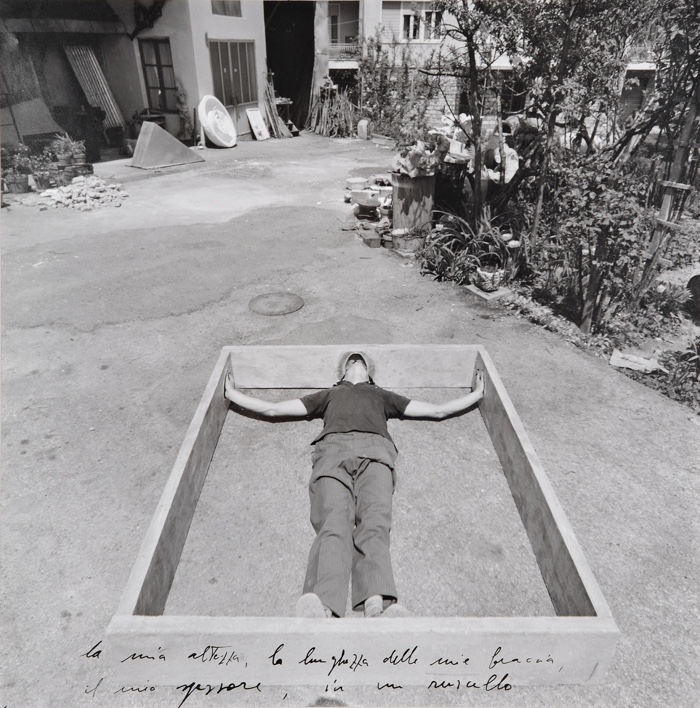

Giuseppe Penone, Alpi Marittime, 1968

Mario Fantin, Italian expedition at K2 (aka Mount Godwin Austen, in the Karakoram range) thermal water sources, Chogo. Left to right: Lino Lacedelli, Cirillo Floreanini, Sergio Viotto, 1954

William Henry Jackson, Castle Geyser, Yellowstone National Park, 1898

Post-Water. Exhibition view at Museo Nazionale della Montagna, 2018 @Museo Nazionale della Montagna CAI Torino

Post-Water. Exhibition view at Museo Nazionale della Montagna, 2018 @Museo Nazionale della Montagna CAI Torino

Post-Water. Exhibition view at Museo Nazionale della Montagna, 2018 @Museo Nazionale della Montagna CAI Torino

Post-Water, curated by Andrea Lerda, is at the Museo Nazionale della Montagna in Turin until 17 March 2019.