Joshua Citarella & Brad Troemel, Ultraviolet Production House, 2015 – ongoing. Photo by Hanneke Wetzer

Morehshin Allahyari & Daniel Rourke, The 3D Additivist Cookbook, 2016. Photo by Hanneke Wetzer

We have transferred almost every single aspect of our daily life onto the internet. Our heartbeats, our bank payments, our musical taste and even our family memories. A group show curated by Nadine Roestenburg and Angelique Spaninks at MU artspace in Eindhoven invites us to do the opposite journey and explore the physical manifestations of the Web.

Materialising the Internet demonstrates that returning to the physical doesn’t bring us back to our starting point. New forms, new aesthetics and gestures emerge as we return to the material, as the digital becomes tangible.

I left Amsterdam and spent 3 hours in public transport just to see this exhibition. I’m so glad i did because the show is a joy! Materialising the Internet is witty, stimulating and entertaining. But if you want to dig deeper, you can also find insight and layers in the exhibition. The various artworks highlight issues such as the potential of the Internet in regards to artistic production and cultural memory, the control that Silicon Valley giants exercises over our lives, the ephemerality of communication tools, the superstitions that surround the most sophisticated pieces of engineering, etc.

Here’s a very quick and partial tour of the show:

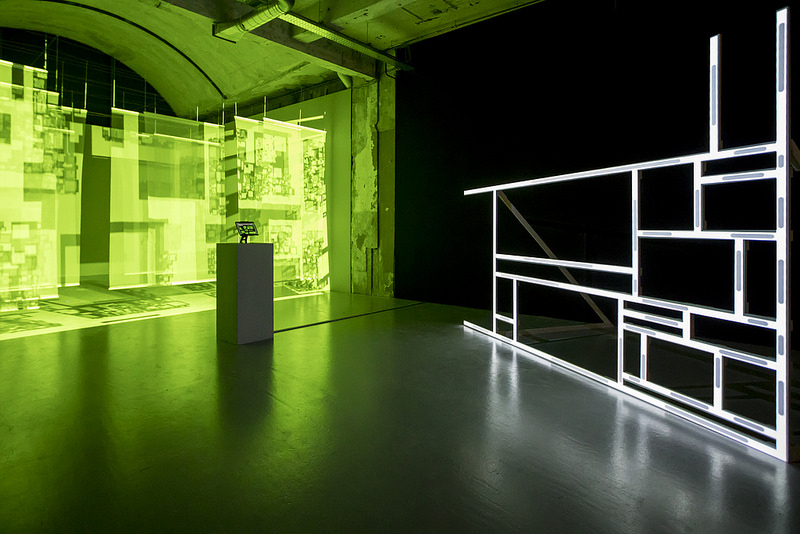

Jip de Beer, Web Spaces, 2016-2017. Photo by Hanneke Wetzer

Jip de Beer, Web Spaces, 2016-2017. Photo by Hanneke Wetzer

Jip de Beer showing some of his models to the next web

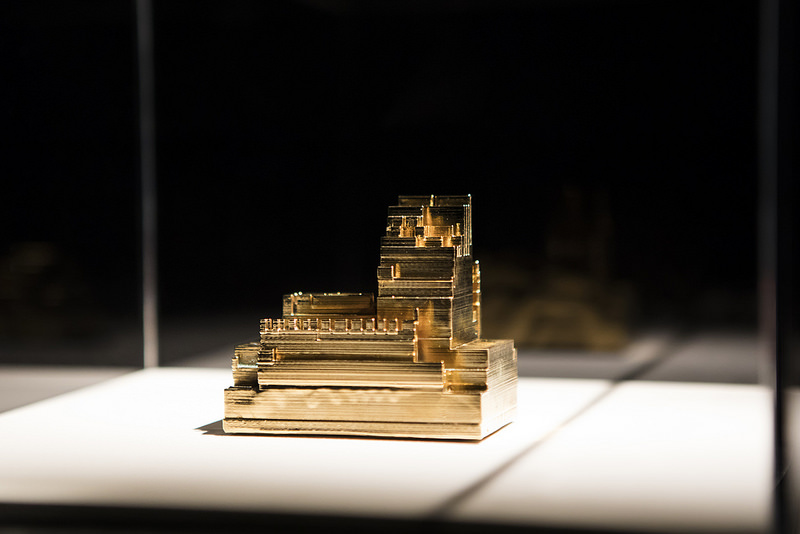

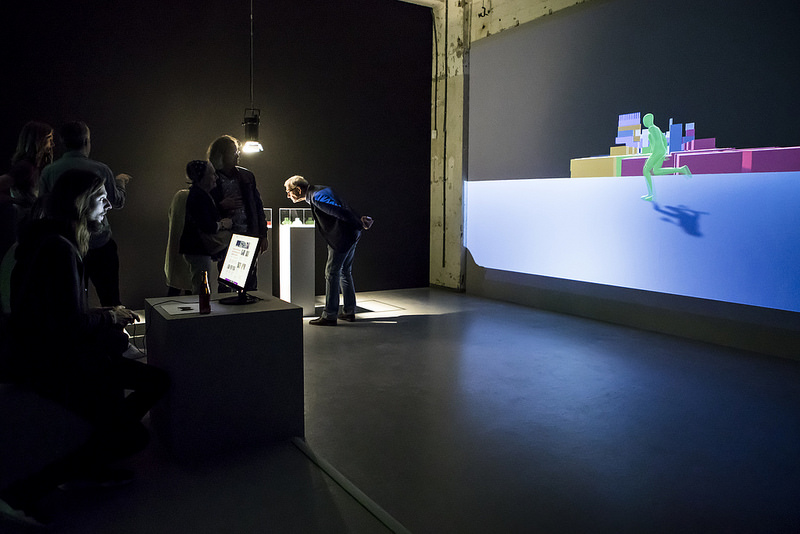

In his series Web Spaces, Jip de Beer literally unfolds the structure of the internet homepages and reveals their hidden hierarchies and three dimensional layers.

His work maps the support structure underneath the architecture of Facebook, Google, Amazon and other famous domains.

MU shows both the interactive installation and the 3d printed models of the websites. The screen installation allows you to a walk around the virtual 3D representation of a particular page while the stunning models of 3 of the most popular websites demonstrate what their physical volumes looks like. The architectures of the websites are incredibly different from one another. Google, unsurprisingly, distinguishes itself by the complexity of its search bar. Facebook, on the other hand, is recognizable by the importance of its ad spaces.

The website’s building blocks are covered in precious metal. The material seems to point to the gigantic power and wealth that the Silicon Valley tech giants have amassed over the past few years but also to the geological origins of our techno-mediated civilization.

Brilliant work that encapsulates perfectly the theme of the exhibition!

Jeroen van Loon, An Internet, 2015. Photo by Hanneke Wetzer

Jeroen van Loon, An Internet, 2015. Photo by Hanneke Wetzer

Jeroen van Loon, An Internet, 2015

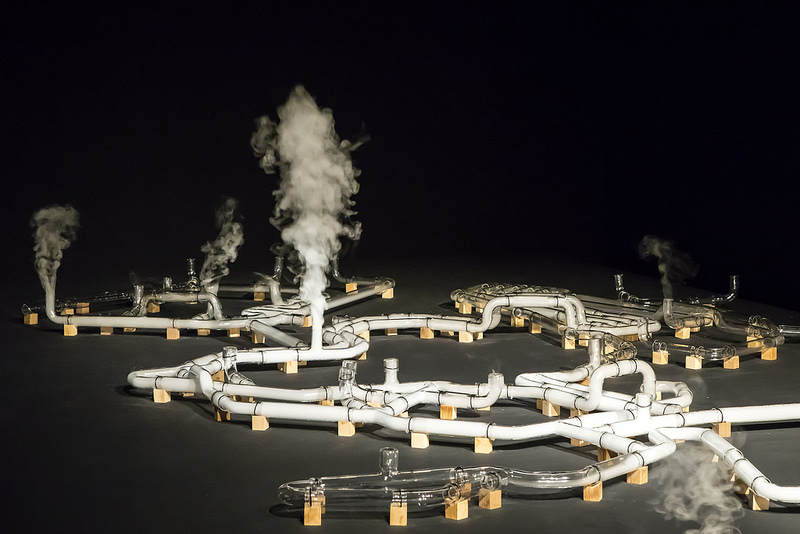

Jeroen van Loon’s An Internet uses glass tubes to reflect the undersea network of fibre-optic cables that connects continents. The system converts the 280 cable names into binary smoke signals. The smoke is puffed into the transparent tubes. You see it fill in the network and evaporate as soon as it encounter an opening in the network.

An Internet is visually seducing. Its vapour and glass representation of an interconnected world suggests the fragile and ethereal dimension of online communication. The installation also alludes to the possible destiny of today’s favourite communication technology:

An Internet shows a vision of a future Internet in which data is no longer produced to be stored for future use, but to be instantly accessible and then lost forever.

How would the internet look if all data were temporary and ephemeral?

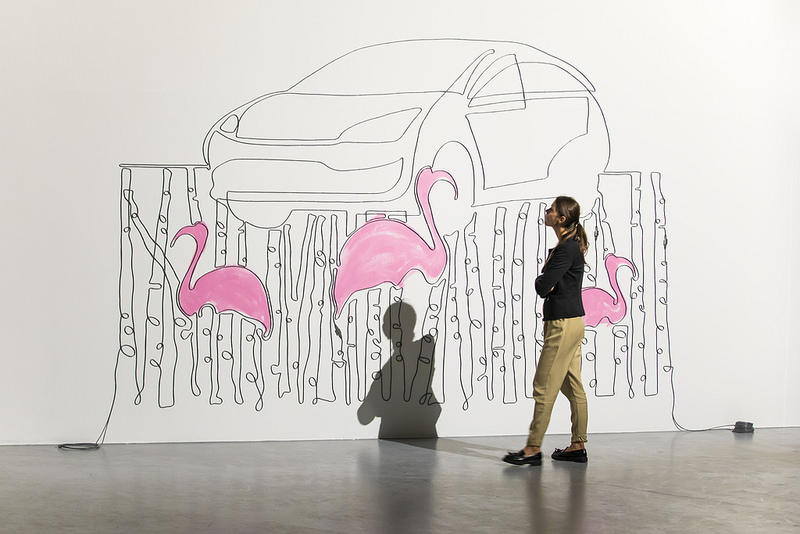

Joshua Citarella & Brad Troemel, Have A Cord Problem And a Spare Half Hour? Try Using Some of That Excess Length To Liven The Room With a Scene From Your Favorite Planet Earth Episode Including The Commercials That Aired During It, Ultraviolet Production House, 2015 – ongoing. Photo by Hanneke Wetzer

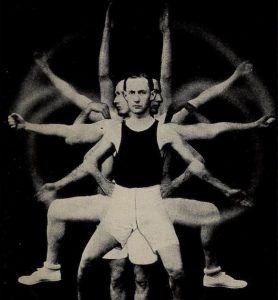

Joshua Citarella & Brad Troemel have found a solution to the problem faced by many young artists: the high production costs of artworks that leaves them indebted before they’ve even found a buyer for their work.

Their Ultraviolet Production House store allows you to order the original artwork of your choice online. After the purchase, you will receive the necessary materials, tools and a manual necessary to build the work “in the comfort of your own home”. The kit comes with a certificate of authenticity.

This innovative model for labor and production cuts the middleman (the gallery) and allows UV to sidestep the costs of overhead, material, studio, tools, etc.

MU ordered two pieces for the show: Incense Fence and Have A Cord Problem And a Spare Half Hour? Try Using Some of That Excess Length To Liven The Room With a Scene From Your Favorite Planet Earth Episode Including The Commercials That Aired During It.

Mieke Gerritzen, My Friends, 2017. Photo by Hanneke Wetzer

According to a research at Oxford University, our brains can manage a meaningful relationship with no more than 150 people at a time. For My Friends, Mieke Gerritzen selected 150 of her closest friends from her 800-plus Facebook contacts, pixelated their profile picture and had it painted.

My Friends gives the ephemeral digital network forged through social media a permanent quality. In a bid to anchor virtual reality, the project materialises part of unbounded digital space and therefore delimits it. The collection of paintings symbolises the age of the network society. The profile photos are rendered in a unique way, magnifying their digital origins.

The images are so heavily pixelated that they anonymize the individuals. Strangely enough however, if you know the people or at least their social media profile, you can still recognize them.

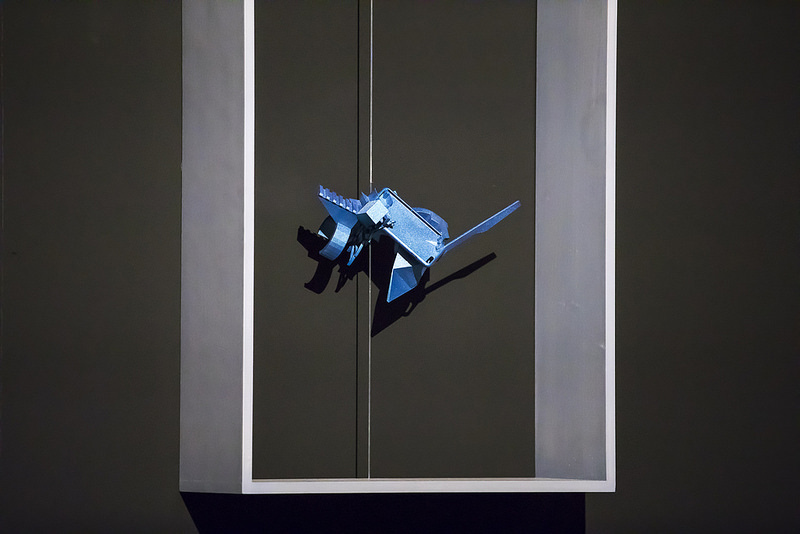

Julien Deswaef & Matthew Plummer-Fernandez, Shiv Integer, 2016 – ongoing. From The 3D Additivist Cookbook. From The 3D Additivist Cookbook. Photo by Hanneke Wetzer

Julien Deswaef & Matthew Plummer-Fernandez, Shiv Integer, 2016 – ongoing. From The 3D Additivist Cookbook. From The 3D Additivist Cookbook. Photo by Hanneke Wetzer

Shiv Integer is a computer programme that randomly picks up models from MakerBot’s Thingiverse, combines them to make odd sculptures, assigns them equally arbitrary names such as Twisty Squeegee Machine then posts the results back on the 3D design sharing platform.

As Matthew Plummer Fernandez writes: The process follows a lineage of Dadaist readymade and chance art, but also explores the authorship-inheritance of Creative Commons licensing, as well as performing an archiving of an Internet subculture, taking cross-database snapshots of 3D-Print culture.

Dries Depoorter, Get Popular Vending Machine. Photo by Hanneke Wetzer

Dries Depoorter, Get Popular Vending Machine. Photo by Kristof Vrancken

Dries Depoorter makes the economics of fake social media success visible with his usual astuteness. His Get Popular Vending Machine sells scratch tickets for a chance to win up to 25.000 followers for your Instagram or Twitter account.

Popularity, influence and prestige for only one euro!

Morehshin Allahyari, Dead Drop Heads, 2017. Photo by Hanneke Wetzer

Morehshin Allahyari’s Dead Drop Heads is a (consciously inadequate) effort to preserve the memory of the antique statues smashed by ISIS when they looted the Mosul Museum in Iraq in 2015. MU visitors can connect their laptop to the work and download a printable 3D file of one of the demolished statue.

“I think the more people who have access to this information, the less that history is forgotten in a way,” Allahyari told Motherboard. “The more files that are saved on people’s computers, even if they’re never printed, the number of PDF files that are read or kept, the more that history that was initially removed by ISIS will be saved.”

Roel Roscam Abbing, Pretty Fly For A Wifi, 2014. Photo by Hanneke Wetzer

Under its haphazard and rustic appearance, Pretty Fly for a Wifi is a wonderfully moving collection of DIY Wi-Fi antennas. It is at once a project history and a manual for the use of DIY Wi-Fi antennas. Many of these designs were once shared on homepages that no longer exist but that are still partially available through the Internet Archive. Pretty Fly for a Wifi revives the designs by rebuilding, testing and documenting them. Each of these pots, pans and cans embodies people’s dream of forging their own communication tools and building an alternative internet.

Valerie van Zuijlen, The Cellular Aura (Version 2.0), 2017. Photo by Hanneke Wetzer

Valerie van Zuijlen, The Cellular Aura (Version 2.0), 2017. Photo by Hanneke Wetzer

As lame as this might sound, many of us have caught ourselves thinking that our laptops and phones must have a spirit of their own. Valerie van Zuijlen investigates the concept of spiritual technology with a performance that offers visitors the possibility to access “the soul” of their digital devices.

All you have to do is turn on the camera of your phone, hand the device to her and watch in wonder as the aura of your phone will glow on a nearby screen.

More photos from the exhibition:

Lauren McCarthy, LAUREN, 2017. Photo by Hanneke Wetzer

Clement Valla, Surface Proxy, Untitled (Still Life 1), 2016 | Untitled (Still Life 2), 2016 | Still Life (Measuring Plants), 2017. Photo by Hanneke Wetzer

Richard Vijgen, Deleted City 3.0, 2017. Photo by Hanneke Wetzer

Richard Vijgen, Deleted City 3.0 + Jan Robert Leegte, Scrollbar Composition, 2017. Photo by Hanneke Wetzer

Jeroen van Loon, Life Needs Internet, 2017. Photo by Hanneke Wetzer

Materialising the Internet, a group show curated by Nadine Roestenburg and Angelique Spaninks, is at MU artspace in Eindhoven until 12 November 2017.