Untitled Installation (2017)

Untitled Installation (2017)

New York-based Lebanese artist Walid Raad AKA The Atlas Group has been one of my favorite artists ever since I saw his work at Documenta 11 back in 2002. His technique of taking a grain of history and constructing elaborate narratives around it works extremely well, especially when talking about the often painful history of Lebanon and its civil war. Raad’s work moves effortlessly between the factual and the poetic while maintaining one of the sharpest political edges in contemporary art.

His recent show at Paula Cooper Gallery in Chelsea, NY was titled Things I Could Disavow: A History of Art in the Arab World. It reflected on the the recent emergence of a new infrastructure for the visual arts in the Arab world, something that Raad himself has been affected by. Accordingly, in one of the pieces, his own body of work becomes the subject of a narrative in which an exhibition of The Atlas Group shrunk.

Interestingly, many texts about the show refer to it as a stage for a play to be acted out and Raad has given performative lectures in this setting at various occasions. In those lectures, he quotes from Jalal Toufic’s The Withdrawal of Tradition Past a Surpassing Disaster, an essay about the famous opening sequence of Alain Resnais’ Hiroshima Mon Amour. Toufic writes that after an event like Hiroshima or the Lebanese civil war, a whole tradition could possibly vanish and Raad suggests that it might be the task of art to “acknowledge and reveal this withdrawal, reflecting the absence of a living being, as mirrors do in vampire movies”.

These are some of the pieces from the show, accompanied by excerpts of the labels which appear to be as much part of the work as everything else:

Appendix XXVI: Artists (2009)

Appendix XXVI: Artists (2009)

This work is based on the names of artists who worked in Lebanon in the past century. In 2002, artists from the future sent me these names by way of telepathy and/or thought insertion and/or using a future technology. That same year, I displayed the names in Beirut in white vinyl letters on a white wall.

Due to a telepathic and/or thought-insertion and/or technical glitch, one name (at least) seems to have reached me in distorted form and was misspelled. Johnny Tahan. It was corrected in red pencil by an unsympathetic critic, a self appointed guardian of Lebanese art and artists.

I spent the last seven years researching the misspelled artist’s life and works, after which I concluded that future artists intentionally distorted Tahan’s name. They were not hailing past “artists” and their works but the color red in the critic’s hand-written corrections.

On Walid Sadek’s Love Is Blind (2008)

On Walid Sadek’s Love Is Blind (2008)

Walid must have sensed that what drew me to his installation was not his work and even less Farroukh’s paintings. He must have sensed that I was literally after the shadows that shaped his walls and captions.

And that in this regard, I didn’t need his permission because these shadows move independently of Sadek’s will, and are prone to irrupting here and there, in forms other than shadows.

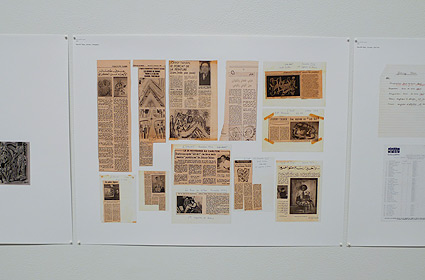

The Atlas Group (2009)

The Atlas Group (2009)

Between 1989 and 2004, I worked on a project titled The Atlas Group. It consisted of photographs, videotapes and sculptures made possible by the Lebanese wars of the past few decades.

In 2005 I was asked to exhibit this project for the first time at the Sfeir-Semler Gallery, the first of its kind white cube space in Beirut. […]

When I went to the gallery to inspect my exhibition, I was surprised to find that all my artworks had shrunk. I decided to display them in a space befitting their new dimensions.

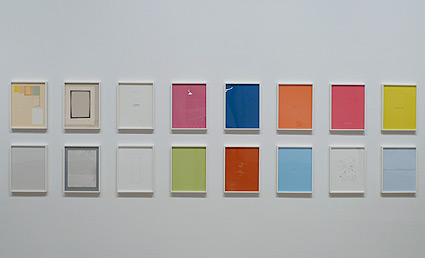

Appendix XVIII: Plates 88-107 (2009)

Appendix XVIII: Plates 88-107 (2009)

It is also clear that these wars affected colors, lines, shapes and forms. […]

I expected such colors, lines, shapes and forms to hide in paintings, sculptures, films, photographs and drawings. I thought that artworks would be their most hospitable hosts. I was wrong. Instead, they took refuge in Roman and Arabic letters and numbers; in circles, rectangles and squares; in yellow, blue and green.

They dissimulated as fonts, covers, titles, indices; as the graphic lines and footnotes of books; as letters, dissertations and catalogues; as diagrams and spreadsheets; as budgets and price lists. They planted themselves inside frames that circulated not front and center but on the periphery of Lebanon’s cultural landscape.

Bigger images.