Putting Teresa Dillon inside a neatly labelled box is impossible. She is an artist, educator and researcher whose practice involves works as diverse as a performance inspired by women whose skin and hair turned yellow while working in WW1 ammunition factories, cardboard structures that explore the affects surveillance architectures have on non-human animals, collective bike rides for energy harvesting, talks & workshops that probe into the mechanisms governing urban life, etc. If that were not enough, she is also the principal investigator at Repair Acts (a multidisciplinary network of people concerned with the necessity to foster a repair, care and maintenance culture) and a Professor of City Futures at the School of Art and Design, University of West England (UWE) in Bristol.

Teresa Dillon, Are You Still Watching?, 2017. Image credit: Ministry of Transport, Sustainable Mobility and Transport Electrification of the Quebec Government

I’ve been meaning to interview her for ages and the upcoming Nø School summer school (where we’ll both be teaching and workshoping along with artists, academics, hackers and other amazing people) in Nevers, France, gave me an excuse to finally get in touch with her.

Teresa Dillon, AMHARC, 2018. Image credit: Karl Burke

Teresa Dillon, AMHARC, 2018. Image credit: Karl Burke

In this interview, we mostly talked about a performance that explores her relationship with machines, her involvement in repair culture and technology’s impact on other animal species.

Hi Teresa! I’m very moved by AMHARC, Are You Still Watching? and other works of yours that look at the impact that technologies and in particular surveillance technologies have on non-human animals. It’s an under-explored area of investigation. At least that’s my impression. What drove you to explore the effect that technology has on other species and in particular on urban wildlife?

Thanks Régine. I agree that dialogues relating to surveillance, technology and cities have largely been human-centered. My motivation to explore the area is rooted across multiple vectors. In my human-ness, I’ve always felt very animal and that our human-ness emerges from an entanglement with other species and our environs. So this base sits within my work and is expressed in different manners through performances, sound works, writing, research and installations, I’ve made in relation to survival, encountering and the techno-civic.

The specific turn towards the effect of technology on other species emerged from work during the mid-2000s projects like OFFLOAD, Systems for Survival (2007), Come Outside (2005), The Listening Chair all took urban space as the carrier so to speak, through which relationships between nature, ecology, systems thinking and cybernetics were explored. These projects were collaborative works, which I created under the name polarproduce and involved many others, such as the artist Kathy Hinde. Back then we were operating from a post-apocalyptic, post-tipping point feeling and so the work embodied these ideas, that is the earthly, physical, bodily and material relations of consumption and its effects on the environs.

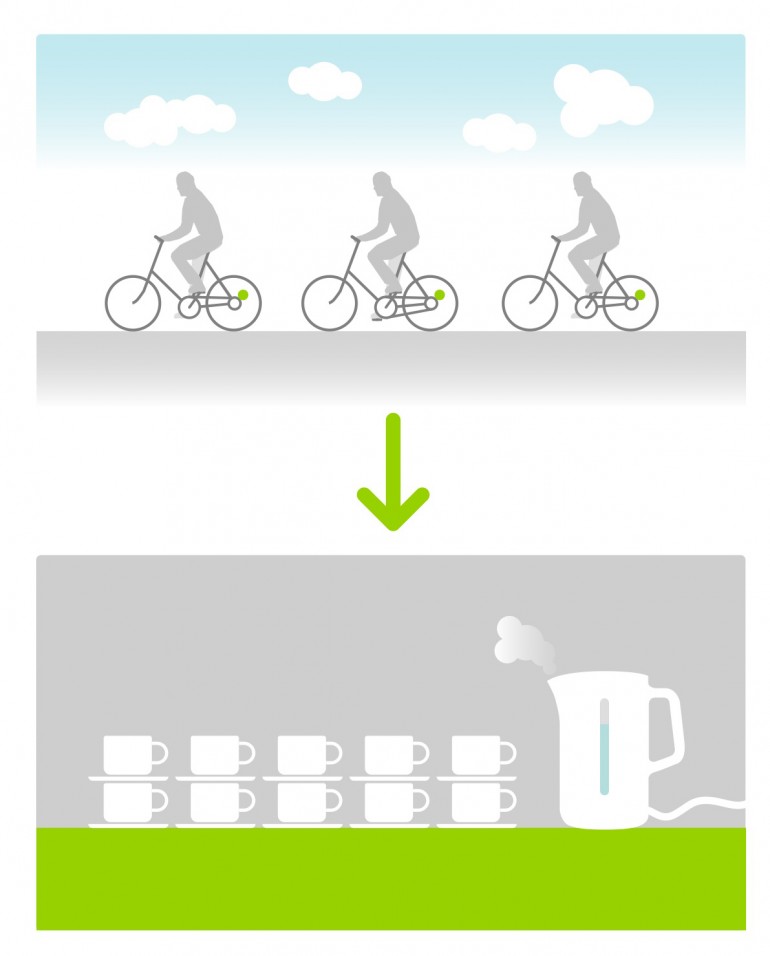

For example for Come Outside we took 25 people on a 2km bike ride in the city. Each bike was augmented with a battery, when the ride was completed, we joined the batteries together and attempted to boil the water for one cup of tea, while delivering a performative lecture on energy transfer under a tree. The Listening Chair simply used a mic to pick up surrounding urban sound at the level of a bat for example, and then transduced this into a range that humans could ‘hear’ like a bat.

I’ve also been interested in the effect of what is defined as noise pollution on animal life and this got extended through research I was carrying out in Berlin between 2014-2016, on how artists (such as Mario De Vega, Martin Howse, Christina Kubisch) are making the human made electromagnetic spectrum (EM) in cities audible. This work led specifically to exploring the effect of EM increase on animal and wildlife.

While this research was developing, I was commissioned to make UNDER NEW MOONS, WE STAND STRONG (2016), which drew on the image of the snowy owl that went viral in 2016. Typically millions of pounds are spent trying to keep birds off such cameras. So there is a tension in this image, the symbol of the owl, celebrated versus the CCTV camera. The installation blows up the scale of the camera, accentuating the bird spikes as hostile architectures, which are designed to ward off birds, or anything that is disruptive to the commercial norm of the city. Low-profile solutions like ultraviolet gels are also used. Birds see in UV and so perceive the gel as a fire, which disrupts their flight patterns.

I’d argue such tactics are similar to what Rob Nixon refers to as forms of slow violence in that it’s not spectacular nor instantaneous but incremental, the effects of which are not necessarily immediate but take place over longer time frames.

Are You Still Watching (2016) extends UNDER NEW MOONS, WE STAND STRONG by contextualising the history of the CCTV camera, its a performative lecture/set design, which also pulls out some animal stories like the owl, or security person who did not want to take care of a dog, which lead to closed-circuits been used as an alternative.

AMHRAC (2018, pronounced arc, it’s the Irish for vision or sight) takes this notion of slow violence further, with the installation itself, taking the form of a totem pole and UV ‘screen’, as a way to imagine spaces of clearing, healing, protection and memory. This is currently developing long paths that look at the histories of animal rights and standing in the city.

Teresa Dillon with Kathy Hinde, The Listening Chair, 2007. Image credit: Teresa Dillon

Teresa Dillon with Kathy Hinde, The Listening Chair, 2007. Image credit: Teresa Dillon

Teresa Dillon, Come Outside, 2006. Image credit: Maarten de Laat

Teresa Dillon, Come Outside, 2006. Image credit: Philip O’Dwyer

Do you see any sign that technology and science are being used in a way that genuinely benefit other living species? On the one hand, it would look like a good idea because of the dramatic loss of biodiversity so we need to use any tool available to slow down this erosion of biodiversity. On the other, we might not want to trust the tendency to use technology to try and solve problems that have often been created by technology in the first place.

If we speak about technology broadly as a tool, then we could argue that one of its main uses has been to extract capital and this includes capital from non-human species. This is where the narrative has to change. Even when technology is used for the common good, which can encompass other species, the narrative tends to the anthropocentric. The origin of such thinking can be traced back to some of the first stories, we told ourselves like in the Bible where we proclaimed that ‘man’ has the ‘right’ to rule over “the fish in the sea and the birds in the sky, over the livestock and all the wild animals, and over all the creatures” (Genesis 1:26). Contextualised in these anthropocentric ways, it becomes very difficult then to answer what is a ‘genuine’ benefit. Therefore there is a deprogramming and decolonisation of the mind and culture that has to happen, and is happening and many people are working on this, which includes bettering the conditions of species with and without tech intervention.

Teresa Dillon, MTCD – A Visual Anthology of My Machine Life, 2018. Image credit: Lydia Goolia

Your performance MTCD – A Visual Anthology of My Machine Life explores the machines that have shaped your “technological know-how and imagination.” Could you explain us what happens over the course of the performance?

Yeah sure, I trace my cyborg life – starting for example with when I was born and placed in an incubator. I spent the first six days of my life in this machine and this is where the story starts. The script which I wrote is approx., 45 mins long, I inhabit the space of the story teller and its intended to be entertaining and goes through for example – the first time I ‘saw’ and ‘used’ the Internet, ICQ, bought a mobile phone, put on a VR head set, shook hands with a robot. I also give some social context or name people who have been instrumental or key to the moment. So the narrative is tech driven but links to people and place. I have created a simple stage design, some noise feedback and worked with the visual artist Luke Bennett (transforma) on the current irritation of images, which are like a triptych that bounce between loops of visual feedback, to photos, comic cut outs, etc, which augment the script. This summer, I’m working to further developing set design, as I will be performing it in Aksioma – Institute for Contemporary Arts, Ljubljana, on 25th and 26th August.

I imagine that although MTCD talks about computers and other engineered devices, it must have a very intimate component. How much of your private life do you think you are revealing with that performance? And conversely, how much in the performance reflects the direct experiences of the public?

It’s revealing too a point about my personal life and perhaps one could infer many other things from it but in trying to keep faithful to a certain track, which describes the encounter with the tech – e.g., what it felt like to touch, what I sensually remembered, who was around when the encounter happened, where was it situated. This allows, I hope for some balance, without it falling down some nostalgic or narcissistic hole. In keeping to specific details, I would hope that some form of extrapolation can occur that allows the audience to locate themselves in the narrative – oh where was I then; or oh yeah, I remember that…. and to make connects.

Some of the public feedback to date has been interesting, people connecting to the story and resonating with parts of it. I am aware of my privilege but I was particularly moved when some young women spoke to me several months after seeing the performance at transmediale 2018 and shared not just how it made media archaeology feel alive for them. It opened up a conversation about our individual and collective ‘she-tories’ and women’s position and representation in media and tech. Basically, the 2017 story connects to how the first sex robot brothels were opened in Glasgow and Barcelona, with robot names like ‘Frigid Farrah’. Farrah is an Arabic name meaning ‘happy, joyful’, I trust, I don’t have to explain what is at play here with the selection of such a name, alongside the connotations of been frigid. Farrah is marketed as been shy and reserved with ‘personality settings’ so you can essentially tweak her level of submission. Between this and the release and pretty fast take down of Microsoft’s Tay, AI chatbot in 2016 and the Foundation for Responsible Robotics report on Our Sexual Future with Robots also released in 2017, which notes how sex robots are mainly gendered as female models with pornographic bodies. These ‘inventions’ and reports mean we are in the midst of a whole ‘new’ set of values, assumptions and possibilities, that will fundamentally shift how we sensually and sexually engage with each other, which opens up a whole other set of questions.

Sorry for a question that will probably make me look silly but what does MTCD stand for exactly?

MTCD is basically my full name in its initial form but I like the way, it also sounds like ‘empty CD’ and looks it might be an acronym.

Teresa Dillon, Under New Moons, We Stand Strong, 2016. Image credit: Fraser Denholm

Teresa Dillon, Under New Moons, We Stand Strong, 2016. Image credit: Yvi Philipp

I love that you sometimes use super low-tech or no-tech materials (like cardboard) to comment on technology. Is that a conscious strategy?

Yes completely. I ‘grew up’ somewhat in the tradition of performance and live art, where for some documenting work was not considered appropriate, as performance is live, it happens in the moment, creating an artefact therefore was not in keeping with the medium. Of course the latter leads to questions of intention and economies but this temporal constraint really appeals to me, as does the affect that post a performance not much is left, aside from these energetic scars in the atmospheres so to speak. So when I found myself working more with objects, it seemed natural when coming from this background that I worked with leftover, discarded material, stuff found on the street that could disappear easily and be turned into material for lighting a fire if needed.

You are the principal investigator at Repair Acts. It is easy imagine what a hacker, an environmentalist or an engineer might bring to the culture of caring, repairing and maintaining. How about the artist then? What can an artistic perspective bring when it comes to stimulating that same culture?

Is it easy to imagine (*/*) or is this the provocation? I mean hacking and engineering are often exploiting the weakness, which is already seeking out the vulnerability and this may not automatically lead to care, particularly if we think how ethics and responsibility have not necessarily been central to the education or training of these professional practices.

More specifically when speaking to artistic practices, I often reference Mierle Laderman Ukeles, Maintenance Art from 1969, which for me is a pivotal reference here, Laderman Ukeles, refers to two instincts the death and life instinct, she associates the death instinct to separation, individuality, ‘following one’s own path to death’; the life instinct is about unification, the eternal return, maintenance. Development and progression is linked to the death instinct the continual need for the new; maintenance, care and repair is linked to the life system, it’s the boring everyday stuff we need to do to keep the ‘things alive’. I’ve written a short piece for the Screen City Journal titled “Working the Break Point: Maintenance, Repair and Failure in Art” (2017) which goes some way to addressing your question, starting with Laderman Ukeles and linking her work to studies in repair from sociology, geography and other disciplines; and to the work of other artists working in the fields of glitch art, and on topics relating to planned obsoletism, systems esthetics and so forth. Artistic perspectives have lots then to bring to the table when it comes to repair cultures and their associated forms of attention, such as care, maintenance and recuperation. Repair Acts was a first step in bringing together different people, their skills and disciplinary knowledge’s together on the topic. The project is ongoing with collaborators and collaborations forming in various countries, so more will be happening in this space. The most recent of which has been the completion of a mapping exercise called “My Square Mile”, which explores changes in businesses registered as carrying out repairs between 1938-2018 in a square mile of around my neighbourhood in the UK, we will now be going forward with this in other cities. A square mile is a good lens through which to observe changes, the research also explores the visual identities associated with repair practices.

Mierle Laderman Ukeles, Washing/Tracks/Maintenance, 1973. Photo: Ronald Feldman Fine Arts (via)

There seems to be a growing interest in repairing and taking care of our objects, whether they are electronics or items of clothing. Do you see the industry pushing back against it or are they trying to adapt and accommodate our growing concerns about waste and consumerism?

Phew have you got some hours ☺ Major shifts are simultaneously occurring, on one hand we have the Ecodesign Directive, which recently pushed through legislation that will kick off in 2021 and require manufacturers of washing machines, dishwashers, televisions, lights and fridges to make their products easier to repair. You have organisations like Restart in London, who are championing policy change and repair parties; iFixit, in the US established in 2003, they have been publishing manuals on how to repair everyday consumer items and produced the Repair Manifesto; on a corporate level, Patagonia consider repair as central to the brand identity and declare repair as a radical act.

When taken seriously repair pushes the question of how we make things in the first instance further up the production chain and demands we make better quality, open products from the start, rather than waiting to recycle or deal with an objects end of life, when it is in a more wasted state.

Across the US, since 2013 The Repair Association has been working on state and federal legislation. So all this is happening but it will be interesting to see when and where this legislation actually hits practice. As you note there is lots of industry kick back, with Apple, John Deere the tractor manufacturer and others finding loops holes, resisting and going in the opposition direction. Essentially they know how necessary and economically viable repair is and yet they want to not just control this market by locking out third parties, but they also want to lock us down into product cycles by gluing, screwing, scaling down parts, bumping you off software, so that objects cannot be repaired or become redundant. If we are to hit UN sustainability goals relating to responsible consumption and production by 2030 then it’s difficult to see how without some serious enforcement, such changes in practices can happen. In response to this creative work arounds will and are always emerging, as will new black markets, growing pressures, green workers movements and changes in practices and politics. All these elements play into this and so when you speak about adapts and accommodations it’s a very complex, involving diverse global flows and relations that become sited in for example laws, standards, scrap yards and workbenches and the square mile around your home and studio.

Any upcoming event, field of research or work you could share with us?

Sure! Some immediate stuff happening over this summer, which relates to all the above includes: Formats of Care with my colleagues in Soft Agency at Floating University, Berlin, 13-16 June 2019; NØ SCHOOL, International Summer School, Nevers, France, 1-14 July 2019 and the MTCD performance at Aksioma – Institute for Contemporary Arts, Ljubljana, 29-30 Aug 2019. I’ve also got some stuff cooking with artists Joana Moll and Jana Barthel and there are some publications coming out (hopefully soon), including ‘Listening Around: Sonic Extractions of the Electromagnetic Spectrum’ in the Journal of Sonic Studies and with colleagues from the University of the West of England, a paper titled ‘Interspecies Urban Planning, Reimagining City Infrastructures with Slime Mould’, which will be in an edited collection of works by Andrew Adamatzky titled Slime Mould in Arts and Architecture (River Publishers.)

Thanks Teresa!